Daumier’s Salon: A Human Comedy

Ridley-Tree Print Rotation

3-23-2014 through 9-13-2014

Honoré Daumier – Man of his Time (video, 7:54)

Lithographic Processes (video 4:48)

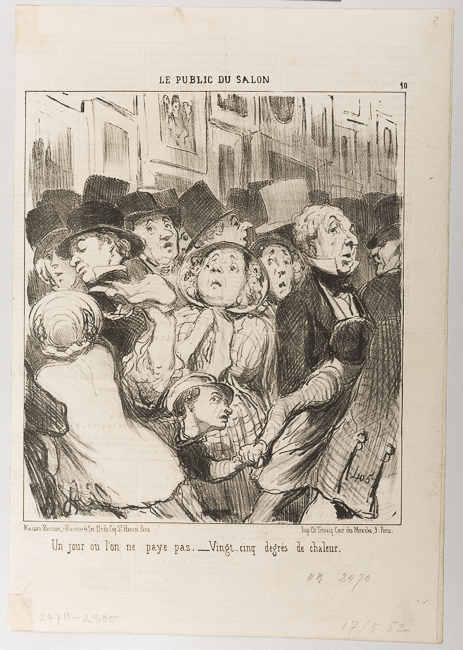

A crowd is uncomfortable in the heat of the exhibition room at the Salon.

The Salon, the yearly art exhibitions in Paris, were actually art fairs which attracted approximately one million visitors from Paris and the provinces. Hundreds of painters and sculptors exhibited. The Salons were the ideal marketplace for the classical painters as well as the new, modern, avant-garde artists. Having little access to private art galleries, these exhibits were especially for the progressive school of greatest economic importance. The jury played an increasingly important role for the future of an artist. Once an artist was rejected from the Salon by a conservative jury, he had most likely no chance to succeed commercially. Very often, a parallel Salon was organized for those artists whose works were refused at the official exhibition . This was the case in 1855, when Courbet’s pictures were considered too revolutionary to be exhibited at the Salon. As a consequence, Courbet opened his own exhibition outside of the official Salon. Baudelaire made some remarks concerning the Salons: “During our time there are only two artists in Paris who are as able as Delacroix: the caricaturist Daumier and the second one is Ingres. All three of them have one thing in common: they express what they mean to say…..” The Salon was for most artists the only possibility to present their works to a greater public. The Salon of 1834 for example attracted some 30,000 visitors on the opening day. During the entire period of two months, a total of one million spectators went to the show. On certain days the ticket price was reduced to 20 sous or was even free of charge, attracting a large number of visitors.

– Dieter and Lillian Noack, The Daumier Register

http://www.daumier-register.org Delteil 2300

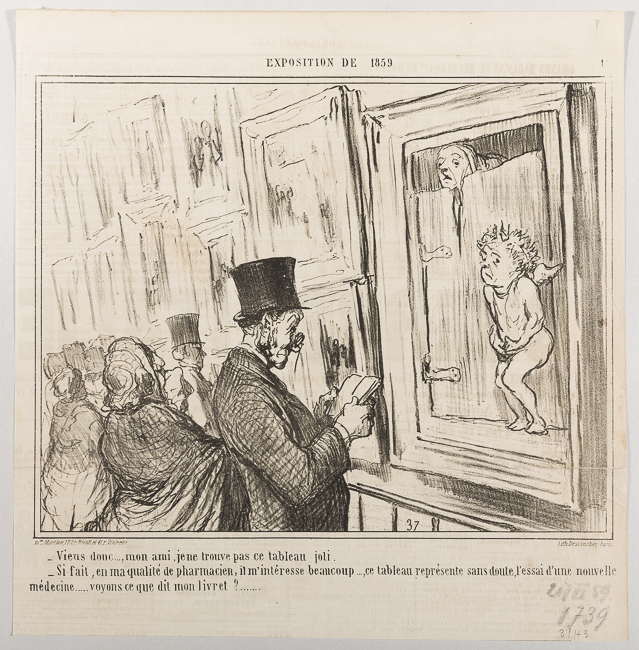

A painting of Cupid waiting impatiently outside of a restroom is being examined by a pharmacist

who thinks that the painting depicts the testing of a new medicine.

There exists for the artist a certain temptation to conceive of medical phenomena as being somehow anti-natural. To many, everything connected with illness and inevitably with death, seems apocalyptically hilarious, terrifying or heart-breaking. Perhaps this is one of the ways in which the mind defends itself against painful truths. In the same way, macabre humor has long been one of the mainstays of the theater and of satirical poetry, and there are plenty of examples of nosological humor, since fear can be experienced by making suffering appear ridiculous. There is a traditional tendency to exaggerate the tyranny imposed on us by our mortal coil. Chamber-pots and clysters have been a subject for jokes ever since these humble objects came into existence.

Because Daumier was a moralist as well as a humorist, his themes were more varied and cruel and he treated them with the severity of a judge, and with profound sadness. The doctors in his lithographs are invariably pedantic, vain, avid, egoistic, or hard and indifferent. They personify the inevitable imperfections of a science in constant evolution and still far from adult in Daumier’s day. Great progress had been made but it was not yet admired and venerated by the wide public that today follows the most esoteric researches with mingled gratitude and reverent terror.

– Henri Mondor, Doctors and Medicine in the work of Daumier, Boston: Boston Book and Art Shop, 1960, p. 13.

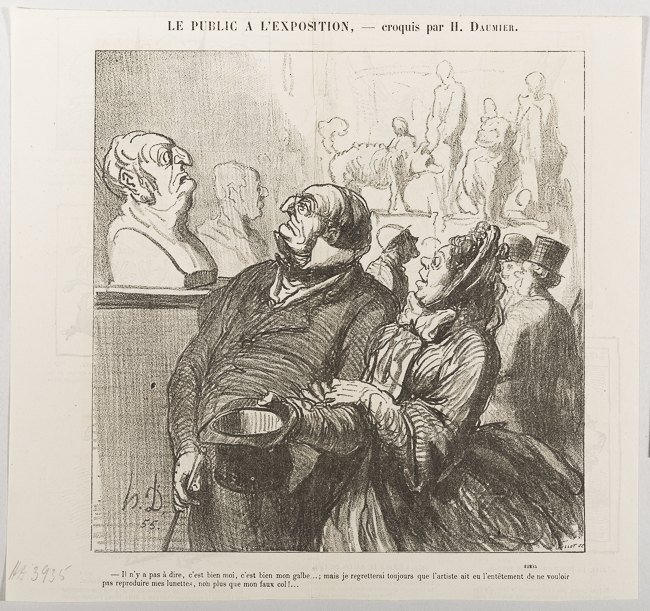

Mr. Prudhomme sees a bust of himself at the Salon. He claims that there is no doubt about it,

it is certainly his profile; but he regrets that the artist had the obstinancy to omit his spectacles.

French actor, writer, and artist Henry Monnier [created the fictional character] Joseph Prudhomme, a figure who, as the subject of Monnier’s own theatrical performances, writings, and caricature illustrations, embodied the nineteenth-century French bourgeoisie. Prudhomme satirized the collective middle class, reflecting the social structure and cultural norms of Paris after “Hausmannization,” the complete revamping of cityscape and population in Paris under Baron Hausmann. The new social landscape meant that class, profession, attitude, and circumstance increasingly defined the Parisian individual.

Monnier first introduced the Prudhomme character in a lithographic series entitled Scenes Populaires of 1830. Prudhomme became the principle motif running through all aspects of Monnier’s career, as the subject of his theatrical works, literary pieces, lithographs, and finished drawings. Also critical to the development of Prudhomme as a character type were Monnier’s contemporaries Honoré de Balzac and Honoré Daumier. The three shared ideas, and each featured the character in his work, Balzac in his writing, Daumier in his own caricatures, and Monnier frequently acted the part of Prudhomme in his theatrical productions. A member of the bourgeoisie himself, Monnier acknowledged his own reflection in Joseph Prudhomme, and as Monnier matured, so did his illustrations of Prudhomme.

The name Prudhomme derived from a verbal pun: in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the word prudhomme was used to describe a man of probity and sagacity; Monnier’s pompous type inverts these virtues. He pretentiously poses as a man of judgment with an appraising air. On stage he talks down to those of his own social rank and ingratiates himself with the elite. Prudhomme was known for his banal, sententious statements. His curiosity led him to ask indiscreet questions, yet rather than waiting for answers, he preferred to talk about himself and his vast experiences.

– Libby Merrill and Brittany Peterson, Traces of the Hand, The Fralin Museum of Art, Charlottesville, VA, 25 January 2013 http://www.virginia.edu/artmuseum/supplemental-websites/traces/traces-2007.15.58.html