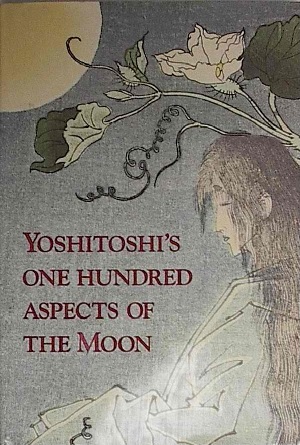

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi

Japanese, 1839-1892

One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, 1889

woodblock print

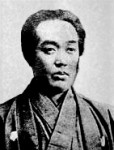

Undated photograph of Tsukioka Yoshitoshi

yo o tsumete

terimasarishi wa

natsu no tsuki

holding back the night

with its increasing brilliance

the summer moon

-- Yoshitoshi's death poem

RESEARCH PAPER

Taiso Yoshitoshi: Japanese “ukiyo-e” wood block print artist is considered one of its true masters. Born near the end of the great Edo Period (1600-1868), when Ukiyo-e were a new and very popular form of art; he mastered all the best of the classical techniques which had been developed by the great masters who had proceeded him. He added to these a vibrancy that still astounds connoisseurs. Then with the changes in the Meiji Period (1868-1912) when Western art principles were introduced into Japan such as depicting light and space, using dissonant color combinations, and focusing on the emotions of individual figure, Yoshitoshi added them to his repertoire. Yoshitoshi became the master of “ukiyo-e” in the Meiji Period and is credited with keeping this unique traditional but beautiful Japanese “ukiyo-e” art form alive long after the Edo Period had ended.

Yoshitoshi was born in Edo (Tokyo) in 1839. Though still very young when his parents divorced, he was sent to live with his second cousins. They hoped Yoshitoshi would carry on their family pharmaceutical business but soon realized he had exceptional artistic talents. So by age ten, Yoshitoshi was sent to apprentice under the Ukiyo-e print master, Utagawa Kuniyoshi. By twelve in 1851, he was Kuniyoshi's most promising pupil. By fourteen, in 1853, he began his own career as an ukiyo-e print designer publishing his first series in 1854.

By 1855, he was known as Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (or Yoshioka). As was traditional for artists in the times, having achieved this level of success, Yoshitoshi was given a name that reflected the master under whom he began his artwork: "Yoshi" from his master Kuniyoshi. (It was only much later in his life, after recovering from a mental breakdown early in 1870's that he changed his name to Yoshitoshi Taiso - meaning Yoshitoshi’s “rebirth”.)

Illustrations of children's stories and cartoons were themes for his first series. But gradually he made increasing numbers of single sheet actor prints. Then, while still in his teens, he changed themes and began publishing triptychs depicting famous warriors in battle. With their profusion of blood, gruesome acts, severed heads and gaping wounds, these renowned prints recreated all the violence and cruelty of the bloody combat described in these tales. To make them even more realistic, Yoshitoshi mixed blood with alum and glue to make the pigment shine: looking as if the blood was still wet.

His obsession with images of violence and demonic acts must in part have been a reaction to the unsettling social and political conditions of the times, as Japan was in the middle of its own violent change from a feudal society to a modern society. Some theorize that the gore depicted in these prints may have been an early hint of the disturbed mental state that eventually led to his breakdown in the 70’s. Others remind us grotesque images like his were common in Japanese paintings as far back as the war-torn Middle Ages, before the years of peace and prosperity brought to Japan under the Tokugawa Shogunate and which define the Edo Period.

By 1865, at twenty-six years old, Yoshitoshi was ranked as the tenth most popular Ukiyo-e artist. By 1868, after the immense success of his publishing “One Hundred Warriors in Battle,” his rank rose from tenth to fourth.

However, by 1871, the popularity of Ukiyo-e was fading out in Japan: most of the old masters had died. Hiroshige and Yoshitora had moved to Yokahama to produce cheap wood block prints for export. Artists were starving. Despite printing images with more popular themes, Yoshitoshi himself became poverty stricken and often had to resort to tearing up floorboards of his home just to keep warm. Destitute and suffering long periods of malnutrition, he had a complete nervous breakdown.

He recovered a year later and became a staff artist for the booming new newspaper industry - working for the Postal Dispatch and other publishers until 1879. His job was “to illustrate the more sensational stories and to make cartoons illustrating the foibles of the day”, … but the Dispatch also commissioned him to design a series of 60 prints illustrating stories that had been reported in the news (Mason, p.376).

The stability of this position provided him enough money to do his own art as well. In that stability, Yoshitoshi began to create images that were more tasteful and pleasing to the eye. He chose lighter themes drawing on a wide range of subjects from Chinese and Japanese literature and Noh dramas and other historical themes. These were subjects in which he had been interested throughout his career. Mason goes on to report some of the stories he did for the Dispatch reminded him of his fascination with ghosts and prompted him to create another of his famous series: One Hundred Ghost Stories from China and Japan. (Mason, p. 376).

By 1884, he had eighty apprentices working for him. His new mature works were astonishingly refined and had a beautiful rightness about them.

In 1888, he published the exquisite images of women caught doing everyday things in “Thirty-two Aspects of Daily Life”.

It had been in 1885 that Yoshitoshi began to design his most famous series of prints: "One Hundred Aspects of the Moon." Fortunately, the series was completed just a few months before his death in 1892. This series of vertical single sheets were so popular in their times that newly printed images from the edition often sold out the morning in which they appeared. It was only later when the whole series was produced bound in albums that full series could be collected.

The mind of this eccentric genius can be seen in these prints. Through them, one enters eerie and mysterious domains filled with phantoms, warriors and impassioned lovers. Though the moon is not always explicitly represented, it's haunting presence is always there in every print. There is an outward tranquility to the prints that lingers there in its muted colors. The quiet beauty and elegant simplicity of the Noh Theater of the times is reflected in many of these prints. The entire set marks a return to the supernatural fascinations of his youth. A circle completed; these haunting images are fittingly the last works of such a great artist.

The prints of this series express both subtle and profound aspects of human emotions. Within the series Yoshitoshi added a full range of colors, used shading to heighten drama, explored a rich variety of compositions, and developed special engraving techniques in order to create the rich variety and intensity of moods; from the sensual to the heroism, whimsical to profound, humorous to melancholy, and the awe inspiring to the tender.

“One Hundred Aspects of the Moon” is perhaps Yoshitoshi’s most acclaimed and popular series, and because of them, his popularity grew and reached levels never before attained by an Ukiyo-e artist even during the height of the classical Edo period. This series showed him at his best, but also demonstrated the technical perfection woodblock printing could achieve before it was replaced by photography.

Unfortunately, Yoshitoshi's mental illness resurfaced three years before his death. There is no explanation for this relapse at the height of his career. Only after his eyesight and health were so deteriorated, did he consent to treatment in Sugaro Hospital. He died in 1892, a few weeks later. Some say his death was by his own hands.

Yoshitoshi was flexible and adaptable: he could walk the fine line between the old styles and new trends. He didn't fit in with his contemporaries but dared to do unique things despite the rigid authoritarianism of the Meiji period. His character bore the stamp of the previous Edo culture: he worked hard, played hard, and was married several times.

He willingly assimilated the Western stylistic influences that came flooding into Japan at this time. Yoshitoshi combined them with traditional Japanese styles and used this combination to revitalize the depictions of even the most traditional subjects of historical heroes, legends and battles. Influenced by the West, Yoshitoshi updated his craft by introducing innovative concepts of light and space. He explored new possibilities in varying the quality of line, mixing texture, and incorporating soft tonalities of color into his work. His images were always primarily figurative. To him, the human form was all-important. He didn't do landscapes. Though some of his triptych images contained exquisite backgrounds, their scenes were just pure products of his imagination rather than the depictions of real places.

In walking this fine line between the old and the new, Yoshitoshi tried to preserve what was unique about wood block printing, while augmenting them with the best aspects from other traditions. This delicate balance is what sets his mature works apart from those of his contemporaries and makes the quality of his prints timeless.

Prepared for the Docent Council, March 2006: by Niki Bruckner

A partial list of his print series, with dates:

* One Hundred Ghost Stories of Japan and China (1865-1866)

* Biographies of Modern Men (1865-1866)

* Twenty-Eight Famous Murders with Verses (1866-1869)

* One Hundred Warriors (1868-1869)

* Biographies of Drunken Valiant Tigers (1874)

* Mirror of Beauties Past and Present (1876)

* Famous Generals of Japan (1876-1882)

* A Collection of Desires (1877)

* Eight Elements of Honor (1878)

* Twenty-Four Hours with the Courtesans of Shimbashi and Yanagibashi (1880)

* Warriors Trembling with Courage (1883-1886)

* One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (1885-1892)

* Personalities of Recent Times (1886-1888)

* Thirty-Two Aspects of Customs and Manners (1888)

* New Forms of Thirty-Six Ghosts (1889-1892)

Bibliography

1. Adapted from a paper by Esther Morris; 10/20/90

2. Kiceluk, Stephanie ed.: “One Hundred Views of the Moon by Yoshitoshi Taiso”, Catalogue Ronin Gallery, New York, New York, 1973-1979.

3. Mason, Penelope: History of Japanese Art: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, New York, New York, 1993.

4. Piper, David, Ed. Tsukioka, Yoshitoshi: The Illustrated Library of Art Mitchell Beazley, Publisher

5. Shin Ichi, Segi, "Yoshitoshi: The Splendid Decadent," Kodansha International, Ltd., Tokyo, 1935.

6. Stevenson, John, "Yoshitoshi’s Women: The Woodblock Print Series," Boulder, Colorado, Avery Press, 1986.

7. “Tsukioka Yoshitoshi: 1839-1892" and “One Hundred Aspects of the Moon.” Pamphlet in SBMA Library: artist files.

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Yoshitoshi was one of the last great print artists of ukiyo-e (floating world pictures) during Japan’s transition to modernity, the Meiji period (1868-1912). Using innovative concepts of space, texture, light, and color, Yoshitoshi produced an enormous number of prints and newspaper illustrations. Beginning in l885, One Hundred Aspects of the Moonwas Yoshitoshi’s largest and most important series. He contributed to it over the next seven years, completing the last three images only two months before his death. Using the moon as a point of departure, Yoshitoshi explored a vast range of human emotions: from awe to tenderness, the sensual to the heroic, the whimsical to the profound, and the humorous to the melancholy.

These prints were produced in the traditional workshop setting involving the expertise of at least four individuals: the artist designer, woodcarver, printer and the publisher. Though credit was generally given to the artist-designers, the final prints depended on the ingenuity of the carvers and printers and the market sensibility of the publisher to realize the visions of artist-designers. By Yoshitoshi’s time, the craft of woodcarvers and printers reached an unprecedented height, resulting in impeccable technical manipulation of Yoshitoshi’s expressive forms, exacting lines and evocative use of colors.

- Important Works on Paper, October, 2020