Tsukioka Yoshitoshi

Japanese, 1839-1892

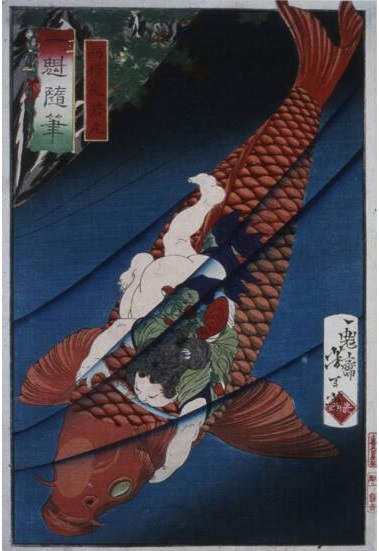

Oniwakamaru or the ‘Demon Child,’ from the series Miscellaneous Sketches by Yoshitoshi, 1872 ca.

color woodblock print on paper

14 1/8 × 9 5/8 in.

SBMA, Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Roland A. Way

1991.147.2

Memorial Portrait of Yoshitoshi by Toshikage, 1892

“holding back the night

with its increasing brilliance

the summer moon”

-Yoshitoshi’s death poem, a haiku

RESEARCH PAPER

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi lived during a period of political and cultural transition in Japan. Born in Edo (modern day Tokyo) in 1839 towards the end of the Edo Period, he witnessed the turbulent beginnings of the Meji Restoration, when the nation reopened its doors to the west and restored the emperor to power. Originally given the name Owariya Yonejiro, he was dispatched at a young age to live with his childless uncle. After his grandfather bought his way into samurai status, his family took the name Yoshioka.

As a young boy, he showed exceptional artistic aptitude, with little interest in learning the pharmacy trade from his uncle. When he was eleven years old, he was apprenticed to the renowned ukiyo-e woodblock print artist, Utagawa Kuniyoshi. Although woodblock printing had been introduced in the 8th century from China, during the Edo Period (1603-1867) the process developed into a highly-sophisticated art form. The term, “ukiyo-e” literally means “pictures of the floating world,” illustrating the transient domain of pleasure quarters, geisha, and theatre, all of which thrived during this relatively peaceful time in Japan’s history.

Kuniyoshi gave the boy the artistic ‘nom de plume’ of Yoshitoshi, affixing part of his own name to that of his juvenile apprentice. Under the master’s tutelage, the boy flourished and at the age of fourteen, published his first woodblock print, a tryptic depicting a dramatic battle scene.

For five years, no further works were published, as Kuniyoshi had become gravely ill. When his mentor died in 1861, the young artist struggled to earn a living from his craft, yet still managed to produce a total of forty-four prints that year.

By 1869, he managed to establish himself as one of the greatest living woodblock artists in the country. Many of his works from this period were scenes of graphic brutality and death, perhaps reflecting the upheaval occurring in Japan.

But by 1871, his popularity waned; maybe the public had grown tired of the violence illustrated in his prints. Destitute, Yoshitoshi lived in poverty with his mistress, at times, burning the floorboards of their home to keep from freezing to death. The artist fell into the first of several episodes of depression.

It’s remarkable that at this difficult point in his life, he produced the woodblock print, “Demon Child.” “Oniwakamaru” was a childhood nickname given to the 12th century warrior, Saitō Musashibō Benkei. The soldier was famous for his immense stature and bravery in battle. The image illustrates a mythic legend of him as a boy slaying the gigantic carp who had devoured his mother. This was not the first time Yoshitoshi portrayed this specific scene; there are both earlier and later depictions executed by himself, as well as numerous other artists, including Kuniyoshi.

Using the synthetic inks which were introduced from the west to Japan in 1860, the saturated use of red, orange, and blue-green is particularly bold. An enormous carp cuts diagonally across the paper, from the upper right corner to the lower left. To convey its monstrous scale, the fish’s tail intrudes into the upper margin of the print.

Straddling the creature is the young Benkei, with dagger clenched in his jaws, ready to slay the beast. He is so consumed with the hunt, he doesn’t notice that some of his clothes have fallen off to the side, exposing his cherubic bottom. His youthful vulnerability is in marked contrast to the ferocity of his violent intent. The fish appears to descend in an effort to shake the boy off: delicately curved and shaded lines indicate faint ripples on the water’s surface and part of the fish’s body color appears lighter under the water. This is all the more impressive because each subtle color required a separate woodblock.

As Yoshitoshi gradually began to recover from his depression, he changed his given name to “Taiso” which means “great resurrection.” Although he was productive once more, he was still not financially secure, and, in 1876, his mistress sold herself to a brothel to help support them both. Moving in with a second mistress in 1877, he continued to struggle. His new companion soon discovered she too had to sell herself to a pleasure house in order to survive.

Newspapers began commissioning woodblock artists to illustrate the dramatic events occurring throughout the country and Yoshitoshi found himself once more in demand. Finally gaining financial security in 1882, he met another woman, a former Geisha with two children, and fell in love. They were wed in 1884. During these later years of his life, Yoshitoshi was the most productive. The series “One Hundred Aspects of the Moon” (some of these prints are also in SBMA’s collection), “New Forms of Thirty-Six Ghosts,” and several triptychs illustrating kabuki theatre were created during this time.

By 1891, Yoshitoshi again began exhibiting signs of mental illness, this time culminating in a complete breakdown. In the early part of the year, he invited his friends to a gathering that turned out to be nonexistent. Admitted to an asylum, he checked himself out in 1892, but did not return to his home and family. Instead, he rented a few squalid rooms and died there alone on June 9 of a cerebral hemorrhage. He was only 53 years old.

Yoshitoshi is considered the last true ukiyo-e artist, carrying forward the refined traditions of woodblock printing into a modern era. After the art of ukiyo-e disappeared, printmaking evolved into shin-hanga and other, more contemporary styles of Japanese woodblock prints. By tapping into Japan’s rich folklore and mythology, replete with ghosts, demons, super-hero warriors, Yoshitoshi popularized a part of the culture which continues today, in the form of artwork, anime, manga, movies and video games.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Becka Chester, 2024.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bruckner, Nikki. (2006, March). “Research Paper, Yoshitoshi, One Hundred Aspects of the Moon.” Docent Website for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art.

https://docentssbma.org/yoshitoshi-woodblock-prints/

Cesaratto, A., Luo, YB., Smith, H.D. et al. (April, 2018). “A timeline for the introduction of synthetic dyestuffs in Japan during the late Edo and Meiji periods.” Heritage Science Journal.

https://heritagesciencejournal.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40494-018-0187-0#:~:text=A%20widespread%20belief%20among%20scholars,colorants%20during%20the%20Meiji%20period.

Chiappa, J.Noel and Levine, Jason M. (2012. July) “Brief Biography of Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892).” Catalogue Raisonné of the Work of Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892).

https://yoshitoshi.net/bio.html

Fiorillo, John. (1999) “Tsukioka Yoshitoshi 1839-1892.” Viewing Japanese Prints.

https://www.viewingjapaneseprints.net/texts/ukiyoe/yoshitoshi.htmlhttps://www.viewingjapaneseprints

Frazer, Doug. (copyright 2024). “Oniwakamaru, the Young Devil Child (Benkei) fighting the Giant Carp in the Bishamon-go-taki Waterfall essay by Yoshitoshi, 1872.” The Art of Japan, Art Gallery Websites by ArtCloud.

https://www.theartofjapan.com/art/oniwakamaru-the-young-devil-child-benkei-fi-by-yoshitoshi

Khan Academy. “The evolution of ukiyo-e and woodblock prints.”

https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-asia/art-japan/edo-period/a/the-evolution-of-ukiyo-e-and-woodblock-prints

Tai, Susan. (2020, August). “Curator’s Choice.” Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Facebook page.

https://www.facebook.com/sbmuseart/posts/today-we-have-a-curators-choice-from-susan-tai-sbmas-elizabeth-atkins-curator-of/10158597850258276/

Wikipedia the free encyclopedia. “Woodblock printing in Japan”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Woodblock_printing_in_Japan

COMMENTS

Dear Friends of Asian Art,

This week we are sending you an image of Yoshitoshi’s dramatic portrayal of a strong boy fighting a giant carp, designed around 1872. As you will discover (below) the boy is known by his childhood nickname, Oniwakamaru or “Demon Child,” because of his unusual strength.

Images of cultural heroes with physical strength and moral character became increasingly popular subjects during Yoshitoshi’s time. By projecting a vision of strength, they may serve as a source of comfort, anticipating the anxiety of modernization as ushered in by the Meiji period (1868-1911)...

Oniwakamaru 鬼若丸, literally “Demon Child,” is the childhood nickname of Saitō Musashibō Benkei 西塔武蔵坊弁慶 (1155-1189), a historical Japanese monk warrior of great strength and loyalty who was active during Japan’s Genpei civil war (1180–1185) that gave rise to the feudal samurai rule over Japan and reduced the power of the imperial family. The legend of Benkei’s mischievous childhood and brave deeds has been the subject of Noh and Kabuki plays as well as in the arts and literature over the centuries.

Oniwakamaru’s exploits were a favorite subject of Yoshitoshi’s teacher Kuniyoshi (1797-1861). In this dynamically composed print, Yoshitoshi approaches the theme differently from his teacher with refreshing vantage points and novel printmaking techniques to enhance the drama. This print illustrates the strong boy’s struggle with a monster carp to avenge his mother’s tragic death. Oniwakamaru clings onto the giant carp while holding a knife in his mouth as the carp dives deeper underwater, defying the frame of the print. Yoshitoshi brings out the natural wood grain of the printing block to give subtle texture to the watery void, while overlaying sweeping gradated blue lines to further suggest motion and speed. His innovative design, creative use of color, and technical precision invigorate the image of strength projected in the well-known childhood tale of this legendary hero.

With warmest wishes,

Susan Tai, Elizabeth Atkins Curator of Asian Art

Holly Chen, Curatorial Assistant, Asian Art

Allyson Healey, Curatorial Support Group Coordinator

- "La Muse", July 1, 2020