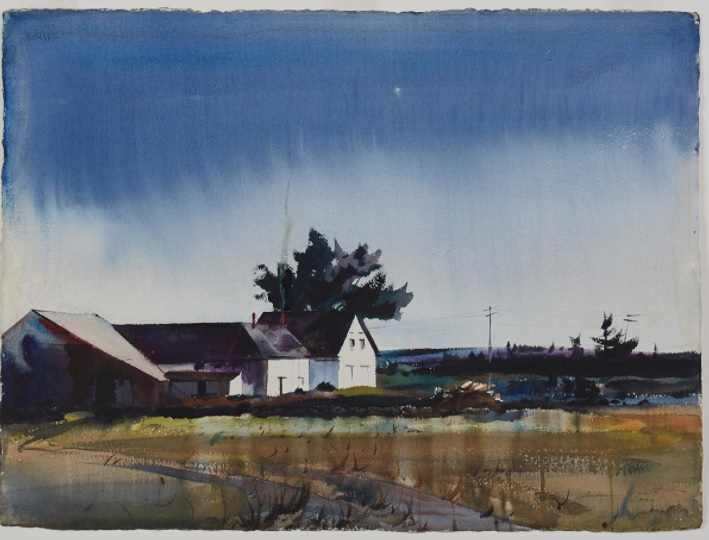

Andrew Wyeth

American, 1917-2009

Evening Star, 1938

watercolor on paper

22 5/8 × 30 1/4 in.

SBMA, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Clifford Ahlers

1965.50

Andrew Wyeth - Self Portrait, 1938

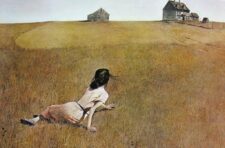

Andrew Wyeth - Christina's World, 1948

COMMENTS

In the summer of 1948 a young artist named Andrew Wyeth began a painting of a severely crippled woman, Christina Olson, painfully pulling herself up a seemingly endless sloping hillside with her arms. For months Wyeth worked on nothing but the grass; then, much more quickly, delineated the buildings at the top of the hill. Finally, he came to the figure itself. Her body is turned away from us, so that we get to know her simply through the twist of her torso, the clench of her right fist, the tension of her right arm and the slight disarray of her thick, dark hair. Against the subdued tone of the brown grass, the pink of her dress feels almost explosive. Wyeth recalls that, after sketching the figure, “I put this pink tone on her shoulder—and it almost blew me across the room.”

Finishing the painting brought a sense of fatigue and let-down. When he was done, Wyeth hung it over the sofa in his living room. Visitors hardly glanced at it. In October, when he shipped the painting to a New York City gallery, he told his wife, Betsy, “This picture is a complete flat tire.”

He couldn’t have been more wrong. Within a few days, whispers about a remarkable painting were circulating in Manhattan. Powerful figures of finance and the art world quietly dropped by the gallery, and within weeks the painting had been purchased by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). When it was hung there in December 1948, thousands of visitors related to it in a personal way, and perhaps somewhat to the embarrassment of the curators, who tended to favor European modern art, it became one of the most popular works in the museum. Thomas Hoving, who would later become director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, recalls that as a college student he would sometimes visit the MoMA for the sole purpose of studying this single painting. Within a decade or so the museum had banked reproduction fees amounting to hundreds of times the sum—$1,800—they had paid to acquire the picture. Today the painting’s value is measured in the millions. At age 31, Wyeth had accomplished something that eludes most painters, even some of the best, in an entire lifetime. He had created an icon—a work that registers as an emotional and cultural reference point in the minds of millions. Today Christina’s World is one of the two or three most familiar American paintings of the 20th century. Only Grant Wood, in American Gothic, and Edward Hopper, in one or two canvases such as House by the Railroad or Nighthawks, have created works of comparable stature...

Andrew’s first notable works were watercolors of Maine that reflect the influence of Winslow Homer. Wyeth began producing them in the summer of 1936, when he was 19. Fluid and splashy, they were dashed off rapidly—he once painted eight in a single day. “You have a red-hot impression,” he has said of watercolor, “and if you can catch a moment before you begin to think, then you get something.”

“They look magnificent,” his father wrote to him of the pictures after Andrew sent a cluster of them home to Chadds Ford. “With no reservations whatsoever, they represent the very best watercolors I ever saw.” NC showed the pictures to art dealer Robert Macbeth, who agreed to exhibit them. On October 19, 1937, five years to the day after he had entered his father’s studio, Andrew Wyeth had a New York City debut. It was the heart of the Depression, but crowds packed the show, and it sold out on the second day—a phenomenal feat. At the age of 20, Andrew Wyeth had become an art world celebrity...

During the 1940s and ’50s, Wyeth was encouraged by two notable supporters of the avant-garde, Alfred Barr, the founding director of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, who purchased, and promoted, Christina’s World, and painter and art critic Elaine de Kooning, the wife of renowned Abstract Expressionist Willem de Kooning.

In 1950, writing in ARTnews, Elaine de Kooning praised Wyeth as a “master of the magic-realist technique.” Without “tricks of technique, sentiment or obvious symbolism,” she wrote, “Wyeth, through his use of perspective, can make a prosperous farmhouse kitchen, or a rolling pasture as bleak and haunting as a train whistle in the night.” That same year, Wyeth was lauded, along with Jackson Pollock, in Time and ARTnews, as one of the greatest American artists...

The artist’s brother-in-law, painter Peter Hurd, Knutson writes, once observed that NC Wyeth taught his students “to equate [themselves] with the object, become the very object itself.” Andrew Wyeth, she explains, “sometimes identifies with or even embodies the objects or figures he portrays.” His subjects “give shape to his own desires, fantasies, longings, tragedies and triumphs.” In a similar way, objects in Wyeth’s work often stand in for their owners. A gun or a rack of caribou antlers evokes Karl Kuerner; an abandoned boat is meant to represent Wyeth’s Maine neighbor, fisherman Henry Teel. Studies for Wyeth’s 1976 portrait of his friend Walt Anderson, titled The Duel, include renderings of the man himself. But the final painting contains only a boulder and two oars from Walt’s boat. “I think it’s what you take out of a picture that counts,” the artist says. “There’s a residue. An invisible shadow.” ...

While seemingly “real,” many of Wyeth’s people, places and objects are actually complex composites. In Christina’s World, for example, only Olson’s hands and arms are represented. The body is Betsy’s, the hair belongs to one of the artist’s aunts, and Christina’s shoe is one he found in an abandoned house. And while Wyeth is sometimes praised—and criticized—for painting every blade of grass, the grass of Christina’s World disappears, upon examination, in a welter of expressive, abstract brushstrokes. “That field is closer to Jackson Pollock than most people would like to admit,” says Princeton professor John Wilmerding...

Should we consider Wyeth old-fashioned or modern? Perhaps a little of both. While he retains recognizable imagery, and while his work echoes great American realists of the 19th-century, such as Thomas Eakins and Winslow Homer, the bold compositions of his paintings, his richly textured brushwork, his somber palette and dark, even anguished spirit, suggest the work of the Abstract Expressionists...

- Henry Adams, "Wyeth’s World", Smithsonian Magazine, June, 2006

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/wyeths-world-117907877/?all

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Son of the illustrator, N.C. Wyeth, Andrew Wyeth is either reviled or revered as one of the most popular American artists of the last century. Known, in particular, for his work in watercolor, Wyeth’s steadfast commitment to representational description stands in stark contrast to avant-garde art of the last century. Nevertheless, landscapes like this, invariably based on the rural surrounds of the family’s 18th-century farmhouse in Chadd’s Ford, Pennsylvania, or their summer house in Cushing, Maine, strike a chord, especially with those nostalgic for a simpler way of life. Wyeth’s mastery of the watercolor medium is evident, especially in his resolute determination not to capitulate to its inherently spontaneous nature. Instead, one senses the artist’s exacting predetermination of the effect of every single stroke of the brush. The white of the paper itself is used to signal the peculiar light of approaching twilight, while the brilliant glow of Venus is expertly communicated by simple contrast with the blue of the sky.

- Important Works on Paper, October, 2020