Grant Wood

American, 1891-1942

March 1941, 1941

lithograph

9 x 11 7/8 in.

SBMA, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. James R. Merrill

1986.70.1

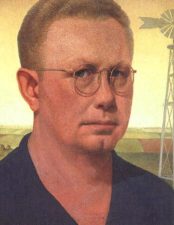

Grant Wood, 1941. Image courtesy of the Figge Art Museum, Davenport, Iowa.

Wood in self-portrait from 1932

COMMENTS

Grant Wood’s Lithographs:

A Regionalist Vision Set in Stone

September 14 through November 8, 2015 Hillstrom Museum of Art

The Hillstrom Museum of Art’s complete set of examples of all nineteen of the lithographs made by famed Regionalist artist Grant Wood (1891–1942) is the result of the generosity of Museum namesake, the late Richard L. Hillstrom and, especially, Dr. David and Kathryn Gilbertson. All but one of the prints were donated by them, including three from Hillstrom alone, four from him and the Gilbertsons together, and the remaining eleven from the Gilbertsons alone. This exhibition, which is the first time these works are being shown as a group, is presented in memory of Hillstrom and in honor of the Gilbertsons.

Wood’s lithos were created in the last half decade of his life and they were the locus of much of his artistic efforts in that period, when he painted only a handful of pictures and spent a great deal of time lecturing. As a group, the prints constitute around one fourth of the artist’s mature body of work. Although any full consideration of Wood’s career must therefore take them into account, they have tended to be neglected or dealt with superficially in the literature on the artist.

Wood had little experience in printmaking prior to beginning his work in lithography, though he appreciated the artistic legitimacy of prints and he had included lithography in the curriculum of the Stone City (Iowa) Art Colony that he helped created and run during the summers of 1932 and 1933. Lithography is a more recent form of printmaking than engraving and etching and because of its process is a freer medium, similar to drawing and more capable of capturing subtle nuances of handling and detail. The artist draws her or his image directly on a slab of fine-grained limestone using a greasy litho crayon. The printing surface is then moistened with water and then inked with oily lithographic ink, which adheres to all the marks made by the artist but not to the unmarked, water-soaked areas of the stone, since oil is repelled by water. A sheet of paper when pressed to the inked stone surface picks up the artist’s image in remarkable detail and fidelity, and in reverse. When the edition of lithographs has been completed, the stone can be carefully cleaned of all the greasy marks from the litho crayon and then reused for a new print.

As a consummate, sensitive draftsman, lithography was a natural for Wood. He must have relished the opportunity presented when Associated American Artists (AAA) of New York contacted him and other prominent artists including Wood’s fellow Regionalists John Steuart Curry (1897–1946) and Thomas Hart Benton (1889–1975) with a program that offered opportunities to create prints that would be marketed and distributed to the general public by AAA. The company, founded by art dealers Reeves Lewenthal and Maurice Leiderman in 1934, was highly successful, remarkable in the economic climate of the Depression. They sold the prints, made in large editions of 250 and offered for $5 each, through department stores and mail order catalogues.

Wood was slow to begin producing lithographs and although his agreement with AAA was made in 1934 and several of the lithographic stones were shipped to him that same year, he did not actually create his first such print until 1937. Wood took printmaking very seriously, and he felt compelled to take time to become proficient in the new medium. And he was pleased how the program run by AAA made art accessible to many, as indicated in his comments in a 1938 letter: “I am so thoroughly convinced of the value of the five dollar original lithographs as the most effective means of producing an art-minded public for the future that I would be delighted to sign a long-time exclusive contract with AAA tomorrow. A contract based on the five dollar print—Depression or no Depression.”

After discussing his ideas for a possible litho with Lewenthal at AAA, Wood typically would make a fully developed preparatory drawing. This served as his guide to transfer the image, in reverse and using a lithographic crayon, onto the lithographic printing stone. The stone was then carefully packed up for shipping to New York, where professional lithographer George C. Miller (1894–1965) would print a small group of trial proofs. AAA would send these to Wood for approval, which he signaled by signing his name in pencil to the proof that he wanted to be used a guide when Miller printed the whole edition.

Wood was pleased with the process and with his prints that resulted from it. He appreciated, too, the democratic aspect of AAA’s program of providing relatively inexpensive but original art to people who were not wealthy. This attitude fit well with his Regionalist precepts of art relating to one’s own life and the locale in which it was lived.

When Wood began his association with AAA and lithography, he was already well established as Regionalism’s most prominent artist. After a period early in his career of working in an impressionist style and pursuing study abroad and European subjects, he famously devoted himself to an art that was American in style and imagery. This approach became firmly established with paintings such as his 1930 landscape Stone City (Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska) and his double figure group American Gothic (Art Institute of Chicago), also of 1930, which made him nationally famous. Wood embraced his role as a fully American artist, writing and lecturing about Regionalism and creating a down-home, overalls- wearing persona to go with it.

But that persona also served for Wood as a convenient way to deflect interest in his personal life, including his sexuality. As a closeted homosexual man, he was in great danger of being recognized as such and because of it falling into disgrace and artistic oblivion. Many of Wood’s contemporaries apparently knew his secret and their discretion helped keep him safe. This included artist Elizabeth Catlett (1915–2012), who came to the University of Iowa to study with Wood and became the first African-American to receive an M.F.A., and who in an interview in 2002 said that everyone knew about Wood’s sexuality. Some newspaper coverage of Wood questioned why the eligible bachelor didn’t seem interested in marrying, and this may have been an important factor in his finally tying the knot, in 1935, with an older divorcée named Sara Sherman Maxon, a marriage that was by ample evidence and many accounts ill-suited and that ended in separation in 1938 and divorce the following year.

Until recently, the major literature on Wood ignored his sexuality. Darrell Garwood’s 1944 study Artist in Iowa: A Life of Grant Wood hinted at some of the artist’s personal life, earning him the lasting enmity of Wood’s sister, Nan Wood Graham. She controlled important resources about Wood after his death, including extensive scrapbooks, availability of images for publication, and her own recollections of her brother, and although she likely knew the truth about Wood, she felt it important to protect his reputation and artistic legacy. She told Wood scholar Wanda Corn that she burned Wood’s letters, a remarkable scholarly loss surely motivated by her concerns about his privacy.

Explicit publication suggesting that Wood was a homosexual seems to have first appeared in 1997 in Robert Hughes’ American Visions: The Epic History of Art in America, where the critic and historian described Wood as “a timid, deeply closeted homosexual.” Since then, several important studies addressing the issue have appeared. In 2000, Henry Adams presented a paper titled “The Truth About Grant Wood” at the February 2000 Annual Meeting of the College Art Association, in a session titled “Regionalist Practices on the Margins of Queer Culture.” In 2005, Joni Kinsey published “Cultivating Iowa: An Introduction to Grant Wood,” in Grant Wood’s Studio: Birthplace of American Gothic, which discusses a meeting in the administration of the University of Iowa in which it was recorded that a charge of homosexuality had been made against Wood. In 2006, James H. Maroney, Jr., first presented his Hiding in Plain Sight: Decoding the Homoerotic and Misogynistic Imagery of Grant Wood, which is available on the Internet with a copyright date of 2013. And in 2010, R. Tripp Evans published his meticulously researched Grant Wood: A Life.

Besides debuting the Hillstrom Museum of Art’s full collection of Wood’s lithographs, the major goal of this exhibition is to consider them in light of the new approach to the artist that does not ignore something so basic as his sexuality. The importance of such an undertaking is expressed by Henry Adams in his paper “The Truth About Grant Wood,” where he states “What I would argue is that homosexual feelings fundamentally shaped [Wood’s] artistic vision, and that his masterpieces are permeated with what might be termed a homosexual outlook . . . .” adding later that “Raising the issue of homosexuality means that we need to confront some sensitive questions, but it also refreshingly reveals that Grant Wood’s art is not just about the American dream and a thoroughly conventional outlook on life. On the contrary, it is about issues which are very real, often painful, and truly significant. If we wish to understand what is truly great about Grant Wood’s achievement, these issues must be addressed.” And addressing these issues will, it is hoped, allow for a multivalent understanding of Wood and his “curiously compelling oeuvre,” to quote James H. Maroney, Jr.

In addition to the lithographs, this exhibit includes additional works by Wood, including two more from the Museum’s collection, a fine portrait drawing donated by Hillstrom and a copy of a 1937 limited edition of Sinclair Lewis’ 1920 novel Main Street for which Wood created illustrations, donated by the Gilbertsons. And the exhibit includes five works lent from other collections, among them drawings on loan from Dr. John and Colles Larkin and from Childs Gallery in Boston (from the collection of Thomas S. Holman), a bronze self-portrait of the artist lent anonymously, and two oil landscape paintings lent by Keichel Fine Art of Lincoln, Nebraska and the Minnesota Museum of American Art in St. Paul. The Hillstrom Museum of Art is grateful to all these lenders.

Numerous scholars of Grant Wood have graciously assisted with inquiries related to the artist, his lithographs, and this exhibition of them. I would like to thank Henry Adams, Wanda Corn, Lea Rosson DeLong, R. Tripp Evans, James S. Horns, Bruce E. Johnson, Paul C. Juhl, Randall Lengeling, James H. Maroney, Jr., Terance Pitts, and Sean Ulmer. I would also like to acknowledge the efforts of students in my Museum Studies class (ART 255) in the Spring of 2015 at Gustavus Adolphus College, including Brandon E. Anderson, Leah M. Creger, Alexander L. Grafton, John M. Granlund, Paige M. Heitzman, Katherine G. Landreville, Elsa R. Larsen, and Alexandra R. Wetterlin, whose individual class presentations each considered one particular lithograph, providing a useful review of over half of Wood’s prints.

In conjunction with Grant Wood’s Lithographs: A Regionalist Vision Set In Stone, the Hillstrom Museum of Art is hosting a public lecture by R. Tripp Evans titled “Crossed Lines: Grant Wood’s Prints for Associated American Artists,” at 3:30 p.m. on October 18, 2015, in Wallenberg Auditorium, Nobel Hall of Science, Gustavus Adolphus College. The lecture, which is free and open to the public, is supported with funds from the Lefler Series of Gustavus Adolphus College and from the College’s Gender, Women, and Sexuality Studies Program. The Museum is grateful for this support.

Donald Myers

Director

Hillstrom Museum of Art

March, the fourth of Wood’s lithos to consider particular months, is a sparse and abstracted image that well indicates the late winter moment just before spring bursts forth. An advertisement for the sale of the print by Associated American Artists notes that “the howling loneliness of the wind-swept hill tells its story of strength and coming fertility,” while another ad calls the lithograph “Grant Wood at his best,” noting the artist’s “genius in being able to endow his subject matter with an extraordinary originality and an amazing sense of design,” and urging patrons to send in their orders for the print promptly since “it will certainly not be long available.”

The design of this lithograph relates to a 1935 painting titled Death on the Ridge Road (Williams College Museum of Art, Williamstown, Massachusetts), which was inspired by a near-fatal auto accident involving Wood’s friend Jay Sigmund (1885–1937), an Iowa poet who encouraged Wood to find inspiration for his art in his own region. The car in which Sigmund was riding was sideswiped by another car as it tried to avoid collision with a truck and Sigmund was injured when his vehicle rolled over twice. Some of the drama of that painting, which was purchased by songwriter Cole Porter (1891–1964), reappears in the print in the dramatic zigzag of its composition, which quickly pulls the viewer into the image, bringing him or her up the hill and abreast of the farmer in the horse-drawn wagon.

The abstract quality of the image is impressive. Wood’s texture is visually exciting and demanding of attention, especially in the lower part of the composition, which is entirely covered with circular strokes and which takes up nearly a quarter of the entire sheet. Other recognizable elements, in addition to the farmer and his wagon and horses, include a house, a barn that’s gabled similarly to others in Wood’s images, and a tree bent by the wind, a motif repeated from the earlier Approaching Storm. Without these specific elements, the print could almost be an example of non- representational art.

Wood experimented with doing this lithograph in reverse but was evidently unsatisfied and only three examples of that version are known to have been printed. A small drawing in charcoal and white chalk that may have been a preparatory work for the earlier version of the lithograph was sold by Nan Wood Graham to the Davenport Museum of Art (now the Figge Art Museum). There is also a related large charcoal drawing (location unknown), with the imagery oriented the same as in the final litho. It has several additional trees, includes in the middle ground a windmill near the house and barn, and has a road that is less artificially placed and that progresses back into the space less vertiginously. In comparing the two images, it almost seems like Wood did not fill in all the details of the drawing when transferring the image onto the lithographic stone but instead decided to enhance the abstract quality of the work by eliminating some of them. The large charcoal may be the same as the work titled Early March that was lent to the 1942 memorial exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago by Dr. and Mrs. Wellwood Nesbit, frequent patrons of Wood from Madison, Wisconsin.

Grant Wood (February 13, 1891 – February 12, 1942) is Iowa’s most famous artist and his painting American Gothic is one of America’s most famous paintings. Wood was born on a farm near Anamosa in 1891 but moved to Cedar Rapids when he was ten years old after the death of his father. From then on, Wood lived most of his life in Cedar Rapids or Iowa City, dying of cancer the day before his 51st birthday.

Wood came to Eldon in 1930 with fellow artist and Eldon native John Sharp and Edward Rowan. He was inspired by the contrast of the modest little house with its (as he described it) “pretentious” Gothic style windows (there is one in each gable end).

Grant Wood’s Place in Art Regionalism

Regionalism in art may be in any style and defined as painting what an artist lives with, in, or around. During the Great Depression, few artists could afford travel costs to study in Europe and consequently the Regionalist movement arose at an opportune time.

Grant Wood became the spokesman for the Regionalist painting movement, when he famously and (somewhat outrageously) remarked that he “got all his best ideas for painting while milking a cow.” As part of playing that role, he frequently wore bib overalls in photos. Even if he did milk cows when he was a young boy, as an adult, this was not a part of his life.

In his uncompleted autobiography, he states that he always remembered his life on the farm and drew from those memories for his paintings. It is important to understand he was using the farm life of the past for his inspiration and ideas. Evidence of modern life on the rural landscape, like telephone poles and tractors, rarely appear in his work.

In its Dec. 24, 1934 issue, Time magazine ran a cover story about Regionalist artists and featured their work in the first ever color spread in that magazine. Time proclaimed that a “truly American art” was being born at last and asserted that these Regionalist painters were creating it. It spoke of an art form free of the strange “isms” of modern European art (cubism, surrealism, etc.), and a print of American Gothic accompanied the article.

The article focused primarily on: Missourian, Thomas Hart Benton (1889 – 1975) who painted Missouri scenes among other things, but lived and worked in New York City. It also touched on Iowan Grant Wood and Kansan John Steuart Curry (1892 – 1942), who painted pictures of life in Kansas, but lived and worked in Connecticut. Wood was the only one of these three artists who really “walked the talk,” – that is, he was the only one of the three who really lived in the place he was painting.

Eventually, Benton returned to Missouri from New York and Wood helped Curry land an artist-in-residence position in Wisconsin, thus leading all three artists to live their lives more closely to their public persons and to their subject matter.

The article also included Wood’s theory on Regionalism: “…regional art rests upon the idea that different sections of the U.S. should compete with one another just as Old World cities competed in the building of Gothic cathedrals. Only thus, [Wood] believes, can the U.S. develop a truly national art.”

Regionalism was not, however, exclusively about making art nor was it an invention of Wood’s. In Iowa, poet and writer Jay Sigmund suggested the idea of Regionalism to Wood. Sigmund, along with author Ruth Suckow, reasoned that artists of any medium should focus on what they know rather than trying to emulate artists from New York and the East.

Wood eventually became a principal spokesman for Regionalism in art for two reasons: first, because his painting American Gothic achieved almost instant fame and second, in the summers of 1932 and 1933, Wood ran the successful art colony at Stone City, which received a great deal of attention from the national press. This too gave both Wood’s ideas and the concept of Regionalism a national audience and legitimacy in the art world.

http://www.americangothichouse.net/about/the-artist/