Vincent Van Gogh

Dutch, 1853-1890 (active France)

Tarrascon Stagecoach (Diligence), 1888

oil on canvas

28 1/8 x 36 7/16 in.

Princeton University Art Museum, Pearlman Collection

Van Gogh - Self-Portrait (Dedicated to Paul Gauguin) - September, 1888

“You used to have a very fine Claude Monet showing four colored boats on a beach. Well, here they are carriages, but the composition is the same in style.” - Letter to Theo, 13 September 1888

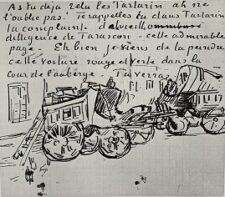

Sketch of Tarascon Diligence, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

COMMENTS

The drama of his mental illness and tragic suicide sometimes overshadows Van Gogh’s sophistication as an artist. As this passage from one of his many letters to his brother suggests, he was a thoughtful craftsman, who, like the Impressionists, painted outdoors and demonstrated a mastery of legible brushstrokes, complex compositional devices, and a brilliant palette. At the same time, however, he transformed their style in his own distinctive way – by applying paint in thick marks, crosshatched strokes, and flowing lines of intense color.

The exceptionally well-preserved paint texture in this work ranges from high peaks of thickly impastoed oils (the yellow wall, gray courtyard, and greens of the carriages) to unpainted canvas (between the spokes of the back wheel). Closed shutters suggest that it is siesta time, and short shadows indicate the early afternoon. The inn portrayed is in Arles, midway on the stagecoach’s route.

Analysis undertaken by the Van Gogh Museum in 2008 identified the roll of canvas that Van Gogh purchased in September, 1888, and which arrived on the 9 or 10 of October. This roll was used to create at least four works, including “Tarascon Diligence,” before “The Bedroom” on 16 October, and then three additional works after. The next roll of canvas, requested on 22 October, would be shared with Paul Gauguin, who arrived the following day.

https://www.pearlmancollection.org/artwork/tarascon-stage-coach/

Van Gogh had just finished painting the “Tarascon Diligence” when he wrote to Theo on 13 October and asked: “Have you reread Tartarin yet? Be sure not to forget. Do you remember that wonderful page in Tartarin, the complaint of the old Tarascon diligence? Well, I have just painted that red and green vehicle in the courtyard of the inn. You will see it. This hasty sketch gives you the composition, a simple foreground of gray gravel, a very, very simple background too, pink and yellow walls, with windows with green shutters, and a patch of blue sky. The two carriages very brightly colored, green and red, the wheels - yellow, black, blue, and orange. Again a size 30 canvas. The carriages are painted like a Monticelli with spots of thickly laid-on paint. You used to have a very fine Claude Monet showing four colored boats on a beach. Well, here they are carriages, but the composition is in the same style”.

The references are to the episode in Alphonse Daudet’s novel Tartarin de Tarascon (1872) where the diligence - or horse-drawn carriage - complains of being exiled in North Africa, and to a painting by Monet of boats on the beach at Etretat that had passed through Theo’s hands at Boussod & Valadon (probably the picture now in the Art Institute of Chicago). Later in the same letter, van Gogh confessed he was completely exhausted after painting “this Tarascon diligence.” It seems likely that he finished it in one session: there is little evidence of studio retouching. It brought to an end a remarkably productive week that included two garden pictures and two pictures of bridges. All five were of motifs within easy walking distance of his house. Three of them are about modes and means of transport, of arrival and departure, as if the pressing thoughts of Gauguin’s imminent coming made him especially conscious of the contrast between an old-fashioned diligence, a modern iron road bridge, and the railroad bridges and viaduct

- Ronald Pickvance, Van Gogh in Arles, New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1984, 188-89

The thrill of anticipation at Gauguin’s coming, and the promise of renewal that came with it, filled every corner of Vincent’s life in Arles. He leaped out of bed early every morning, rushed to his studio, and worked until sunset. “I am vain enough to want to make a certain impression on Gauguin with my work," he confessed, “so I cannot help wanting to do as much work as possible before he comes." ...

In Pont-Aven, Vincent’s comrades [Gauguin and Bernard] had been developing a paint surface that barely betrayed a brush at all. Following Anquetin’s lead, they had pursued the Cloisonnist rhetoric about “plates” of color and the paradigm of stained glass to their logical conclusion. Where Cézanne had used brushy, thinly painted planes and brickworklike strokes to construct his faceted scenes, Gauguin and Bernard divided their images into areas of pure color and then filled each area with thin paint applied in smooth, impassive strokes. Vincent surely knew of these innovations through his correspondence with both artists, and even occasionally tried them himself when the urge to solidarity overtook him.

But inevitably his manic brush rebelled. … By the end of September, with Gauguin’s arrival only weeks away, Vincent’s balks, debates, and rebuffs had combined into a full-throated rebellion against his fellow triumvirs of the new art. “How preposterous it is,” he wrote sister Wil seditiously, “to make oneself dependent on the opinion of others in what one does.” In opposition to the decorative, cerebral imagery advocated in Brittany, he had put forward the elements of a very different art: an art of portraits, not parables; figures, not fantasies; peasants, not saints; and art of impact, not enigma; of paint, not glass. But most of all, an art of feeling – “heartbroken, and therefore heartbreaking.” Color, with its magic, musiclike power to arouse emotions, played a central role. “I use color … to express myself forcibly,” he wrote. …

The right color combinations, he insisted, could arouse the full range of human emotions; from the “anguish” of broken tones to the “absolute restfulness” of balanced ones; from the “passion” of red and green to the “gentle consolation” of lilac and yellow. … And he rejected outright Cloisonnism’s relegation of color to a mere element of design – a decorative deduction – rather than the “forceful expression” of “an ardent temperament.” …

If color was his music, the brush was his instrument. Strokes could be “interwoven with feeling,” Vincent maintained, to elicit a range of emotions: from the “pain” of impasto, to the exhilaration of stippling; from the serenity of smooth paint (“like porcelain”), to the sublimity of radiating strokes.

- Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith, Van Gogh: The Life, New York: Random House, 2011, 619, 630-632

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

In a letter to Theo written on October 13, 1888, Vincent described with excitement this very painting—one of some fifteen that he made as a decorative ensemble for the Yellow House in Arles that he had prepared to welcome the painter Paul Gauguin. The subject of this painting was inspired by a specific scene that featured a diligence (the French term for this type of stagecoach) in a farcical novel by Alphonse Daudet called "Tartarin de Tarascon" (1872). As Vincent wrote to Theo, “Well, I’ve just painted that red and green carriage in the yard of the inn [in Arles]. You’ll see.” As always, reality and fiction were readily interchangeable in Vincent’s imagination.

After just eight months in Provence, Van Gogh’s art had entered a newly confident phase of execution. Stark complementary contrasts of red and green, blue, and yellow are allowed to reverberate off the canvas. Pigment is visibly slathered on with the brush, so that the entire canvas surface is activated. In his recounting to Theo of this painting’s genesis, Van Gogh called out both Claude Monet and Adolphe Monticelli as inspirations for the vivid palette and thickly

applied brushwork, respectively.

- Through Vincent's Eyes, 2022