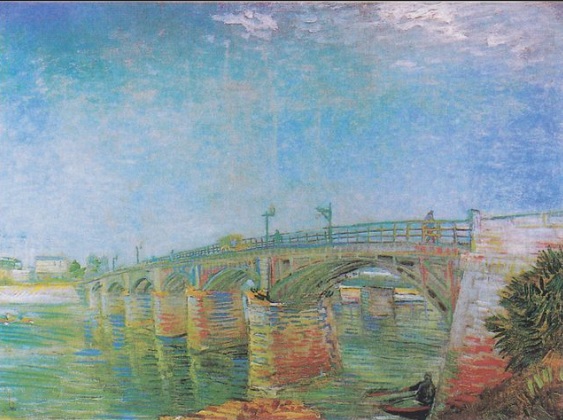

Vincent Van Gogh

Dutch, 1853-1890 (active France)

Bridge across the Seine at Asnières, 1887

oil on canvas

21 x 28 3/4 in.

Private Collection

Van Gogh - Self-Portrait, Spring 1887

"Last year I painted almost nothing but flowers to accustom myself to a color other than grey, that’s to say pink, soft or bright green, light blue, violet, yellow, orange, fine red. And when I painted landscape in Asnières this summer I saw more color in it than before. I’m studying this now in portraits." - Letter to Willemien van Gogh, October 1887

COMMENTS

Theo had always pushed his brother to do landscapes, adamant about both the reparative power and the commercial appeal of nature’s beauty. But those calls had rung hollow to Vincent ever since Theo had rejected the heathscapes from Drenthe as too derivative of the brothers’ childhood favorite, Georges Michel. In the thrall of Millet and the fervor of “The Potato Eaters”, Theo’s advocacy had come to look increasingly like obstructionism designed merely to frustrate Vincent’s passion for figure painting. That impression seemed confirmed in Antwerp when Theo pushed him to return to Brabant and paint landscapes rather than come to Paris to gratify his craving for nude models. In response, Vincent dismissed plein air painting as unchic (“[Parisians] care little for outdoor studies,” he insisted) and claimed that working outdoors was bad for his health.

In the year since, he had hardly ventured beyond the precincts of the rue Lepic apartment. He documented his neighborhood and the views from his window (just as he did in every new home), but rarely visited even a park. In a city obsessed with escaping itself in the summer heat, he spent the entire summer holed up in his studio, painting bowl after bowl of withering flowers.

But all that changed in early 1887. Before the trees had even budded, Vincent lugged his paint box and equipment over the butte, past Montmartre’s ramshackle margins, past the crumbling fortifications that girdled the old city, and through the ring of factories and warehouses that circled the new one. Finally, about three and a half miles out, he hit the banks of the Seine not far from the Île de la Grande Jatte, the summer playground immortalized by Seurat.

Over the next months, at points all along this route, he marshalled his paints and brushes and his conciliatory eye in an all-out campaign to reclaim his brother’s favor. Forsaking years of strident rhetoric and uncompromising images, he embraced the art that Theo had advocated so long in vain: Impressionism. It was a reversal abrupt and dramatic even by Vincent’s volatile standards. He planted his easel on the broad boulevards and suburban highways, beside industrial monuments and “banlieue” vistas – all subjects favored by the new art but long ignored by him – and painted them in the bright colors and drenching sunlight that had been the subject of so many heated debates on the rue Lepic.

Especially on the banks of the distant Seine, where spring came early, he made amends for his years of obstinacy. He filled canvas after canvas with the Impressionists’ signature images of bourgeois leisure: a Sunday rower on a glistening river, timid waders at the water’s shallow edge, a straw-hatted stroller on the grassy riverbank, a boatman resting in the shore’s dappled shade. He painted tourist landmarks like the Restaurant de la Sirène, a Victorian pleasure palace that loomed over the little riverside town of Asnières, just downriver from La Grande Jatte. During the high season, the Sirène’s long verandas filled with spectators for river regattas and day-trippers fleeing the stifling city. He painted the huge bathing barges anchored just offshore and the fashionable waterside restaurants set with linen and crystal and bouquets of flowers – scenes as far from the hovels of Nuenen as imagination could take him – all rendered in the pastel tones and shadowless, silvery light he had decried so vehemently, in words and images, only months before.

Throughout the spring and into the summer, he returned again and again to the same area around Asnières – outings that had the added benefit, if not the intention, of absenting him from the apartment. Theo “look[ed] forward to the days when Vincent would wander off into the country,” Dries Bonger recalled. “He would get peace then.” Liberated from his long resistance, and desperate to find the key to his brother’s favor, Vincent tried virtually every technique in the Impressionists’ repertoire, all of which he had studied carefully, even in rejection.

His experiments with Impressionist brushwork had already begun earlier that winter in still lifes and portraits, like the ones of the Scotsman Reid. Because the gospels of Millet and Blanc were relatively silent on the application of paint, his brush was free to test the new art’s texture even as he continued to attack its fainthearted palette. Already in Antwerp, the dense, featureless surface of “The Potato Eaters” had given way to the “enlever” contours of his portraits, and these in turn to the scumbled encrustations of the previous summer’s flowers. As early as January 1887, he experimented with both the thinner paint and the more open compositions of Impressionists like Monet and Degas. In the spring, he abandoned altogether the heavy impastos and compacted surfaces of the past and set out to try his hand at the whole complex calligraphy of brushstrokes that distinguished the new art as much as its color and light.

The paintings of spring and summer were filled with the fashionable shorthand of dashes and dots. He tried them in every size and shape: from bricklike rectangles to comma-like curls to bits of color no bigger than flies. He arranged them in neat parallel ranks, in interlocking basketweaves, and in elaborate, changing patterns. Sometimes they followed the contour of the landscape; sometimes they radiated outward; sometimes they all swept across the canvas in the same direction, as if blown by an unseen wind. He applied them in tight, overlapping thickets; in complex confederations of color; and in loose, latticelike skeins that revealed the underlayer of paint or ground. His dots clotted and clustered, filled large areas with perfect regularity or exploded in erratic swarms.

In his race to make up for lost time, he jumped back and forth over ideological chasms that brought other artists to blows, often combining Divisionist dots and Impressionist brushwork in the same image. Eschewing or ignoring Seurat’s optical claims, he mixed the colors on his palette exactly as he had always done, rather than apply them “pure” and trust the viewer’s eye to blend them. His “pointille” came and went, faded in and out from painting to painting, even within paintings, as his patience for the painstaking method waxed and waned.

On days too cold or wet for the trip to Asnières, he practiced all these new liberties on an old and elusive subject: himself. Risking only cheap sheets of cardboard or scraps of paper not much bigger than postcards, he painted the dapper, chapeauxed image in the mirror in every combination of palette and brush; from sketches in broad slashes to mosaics of brushwork in every pattern, density, and dilution. Finally, he committed himself to a real canvas …

In all these experiments, Vincent had an advantage he could not have anticipated. Years of seeing with an etcher’s eye had prepared him unknowingly for the fractured image making of the new art. He had long since mastered the interweaving of solids and voids: rendering contour and texture through hatching and stippling; manipulating form through the density and direction of markings. To school his hand in the new style, he had only to recruit these old skills in the service of his new understanding of color – to substitute Blanc’s matrix of simultaneous contrasts and kindred hues for the binary interplay of his beloved black-and-whites.

By connecting these two wellsprings of picture making, the jabbing images of that spring and summer finally freed Vincent from the unforgiving linearity of realism and opened up his paintings to the spontaneity and intensity of his best drawings.

- Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith, Van Gogh: The Life, New York: Random House, 2011, 530-532

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Like Monet and the Impressionists, Van Gogh actively sought out the suburban leisure spaces now easily accessible by train to Parisians. However, like his new friends, Signac and Bernard, he selected motifs that prominently featured the markers of modernity, including gaslit bridges, such as this one over the Seine. This view is of the more industrial town of Clichy, as seen from the village of Asnières to which Vincent was able to walk from the city over the very bridge depicted. Evident in this painting is Van Gogh’s rapid assimilation of lessons gleaned from the likes of Monet and Sisley, but also the pastel palette of pinks, blues, and purples that he so admired in the Japanese woodblock prints of Hiroshige.

- Through Vincent's Eyes, 2022