Juan de Valdés Leal

Spanish, 1622-1690

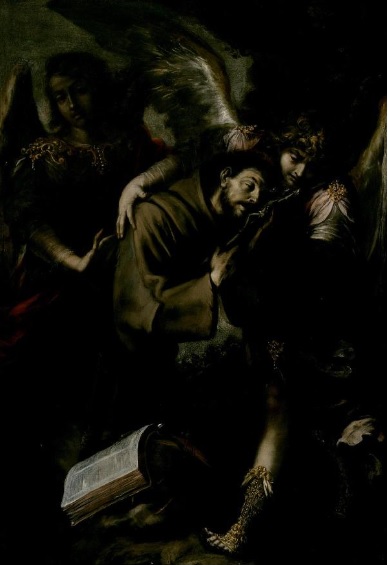

The Ecstasy of St. Francis, 1660s, probably

oil on canvas

61 1/2 x 42 in.

SBMA, Bequest of Suzette Morton Davidson

2002.31.5

COMMENTS

Juan de Valdés Leal (1622-1690) holds an important place in 17th century Spanish painting. Long overshadowed by his more famous contemporaries, Valdés Leal is becoming better known thanks to the research of historians of Hispanic art such as Elizabeth Trapier du Gue and to a renewed interest in Spanish art of the seventeenth century.

A master painter of the Spanish High Baroque, Valdés Leal's career coincided with the last two decades of Spain's “Siglo de Oro”, or Golden Age (1565-1665). The cultural expansion enjoyed by Spain during these hundred years was unprecedented in her history. It was based on her conquest and exploitation of the Americas and on the power and profits she gained from her dominions in Italy, the Lowlands, and Portugal. Another impetus to the “Siglo de Oro” came from Catholic Spain's triumphs over Islam in her victories over the Moors at home and over the Turks at Lepanto. Between 1565 and 1665 Spain became one of the most powerful nations in the world as well as a center of piety and artistic excellence.

The greatest, richest empire on earth, Spain, considered herself a leader in the arts, superior to Elizabethan England in literature and to contemporary Italy in art. There was some justification for this self-esteem. The “Siglo de Oro” was in literature the age of Cervantes (1547-16l6), Lope de Vega (1562-1635), Calderon (l600-1681) and inpainting of El Greco (1548-1614), Zurbarán (1598-1664), Murillo (1517-1682), Velásquez (1599-1660), Ribera (1588-1652) and Valdés Leal.

The cultural efflorescence Spain enjoyed during its Golden Age was strongly conditioned by the religious fervor of the period. As the stronghold of the Counter-Reformation, Spain adhered to the course set by the Council of Trent (1545-1563) for the Church and the Arts. Baroque art, as it later came to be called, was a direct result of the Council's dictates. Nowhere in the Catholic world was the pietistic; evangelical thrust of the Counter-Reformation more apparent than in Spain of the “Siglo de 0ro”.

In addition to influencing the shape that the arts would take, the administration of the Catholic Church in Spain became a model of efficiency and integrity as the Inquisition sought out and punished heresies. In 1547, the dark confessional box was introduced and in 1614, made obligatory. Indulgence peddlers disappeared and indulgences, for the most part, were given for pious devotions and works of charity rather than for financial contributions. Instead of retreating before the advance of Protestantism or free thought, the Catholic clergy set out to recapture the mind of youth and allegiance of power. The spirit of the Jesuit Order: confident, positive, energetic, and above all, disciplined, became the spirit of the militant church. Nowhere else on the globe had religion such power over the people as it did during Spain's Golden Age.

The self-conscious morality of the Counter-Reformation created a puritanical age in Spain which profoundly affected the arts. This new morality informs one of the most influential treatises on art, Francisco Pacheco's "Arte de la Pintura" (1649), which laid down rigid rules regarding the presentation of holy figures. Even minor considerations such as the discreet draping of Cherubim were carefully legislated. Pacheco's denunciation of the undraped human form was to have serious consequences for Spanish art in general and for Valdés Leal in particular. According to Pacheco, chastity, decorum, and unquestioning faith were the governing principles of art. "The chief end of art" Pacheco wrote, "is to persuade men to piety and to incline them to God."

Of the many cities that flourished during the "Siglo de Oro" none surpassed Seville, the major port of entry for the Spanish silver fleets. It was there that Juan de Valdés Leal was born in 1622, the same year that another native son, Velásquez, left it for Madrid. The early years of Valdés Leal's life are sparingly documented. It is known that his father was Portuguese, one Fernando de Nisa, and his mother Spanish, Antonia Leal Valdés, but no explanation is given for his choosing to use his mother's name alone. In this respect our painter is akin to Picasso who also gave up his father's name. Perhaps, like Picasso, this could indicate a rift with the father; or it may have been chosen to ensure easier acceptance in Seville where a Portuguese surname was not desirable on account of the far from friendly relations existing between Spain and Portugal at the time. There is also mention, in the documents concerning Valdés Leal, of an otherwise mysterious silversmith step-father, Pedro de Silva.

Although no documentary evidence exists to shed light on Valdés Leal's early training, it is commonly assumed that he received his early apprenticeship in Seville. He could not have chosen a better place. A vital artistic center, Seville was not only the home of Velásquez but also of Murillo and Zurbarán, as well as of lesser-known artists such as Juan de las Roelas and Francisco Herrera the Elder. It was also the port of entry for the paintings Ribera sent back from Spanish Naples. The art of Rubens, so eagerly sought by the Spanish court, was likewise familiar to Seville. It was a glorious and challenging place for an artist and Valdés Leal, like so many of his contemporaries, sought both to emulate and challenge these great masters.

In fact, throughout his career Valdés Leal was to work in a variety of modes. This has led detractors to decry a seeming inconsistency in his work. There is a definite Rubensian influence apparent in his "Assault by the Saracens on the Convent of San Damiano, Assisi" (Museo Provincial de Bellas Artes, Seville). His realistic, tenebrous "Saint Andrew" (Church of San Francisco, Cordoba) evokes both Ribera and Caravaggio. The clear linear austerity of his "Saint Mary Magdalene of Pazzi and Saint Agnes" (Monasterio de los Carmelitas Calzados,Cordoba) recalls Zurbarán, while the gentle sweetness of his "Immaculate Conception" (National Gallery, London) is inspired by Murillo. Velásquez provided the prototype for the controlled painterly elegance of the "Saint Sebastian" (Church of the Magdalene, Seville), and the crystal clarity of Netherlandish art informed the detailed accuracy of Valdés Leal's late vanitas still lifes. However, eclectic alternation of modes should not be seen as artistic uncertainty but as necessary steps in attempting to evolve a unique style.

Of direct impact on Valdés Leal's artistic development was his move to Cordoba in 1642. Compared to sophisticated Seville, Cordoba was artistically provincial. Such a backwater, however, allowed a twenty-year old fledgling artist the opportunity to develop a distinctly personal style out of the shadow of the master painters who otherwise influenced his art.

It was in Cordoba that Valdés Leal in 1644 produced his earliest known work, the "Saint Andrew for the Church of San Francisco". In this figure one can already see elements which were to become an integral part of his artistic vocabulary: a powerful handling of facial features, hands and feet uncomfortably fitted to an awkwardly articulated body, a compressed torso and clothing more akin to a study for drapery than to fabric covering a body. Another typical characteristic of Valdés Leal's style is the composition divided into a dark “repoussoir” of rocks at the left which is counterbalanced at the right by a space-defining distant landscape bathed in soft light beneath a turbulent sky.

In his series of paintings of the life of "Saint Claire" executed during this same early period for the Convent of Carmona, another aspect of Valdés Leal's style becomes evident: his delight in inventing and painting elaborate metal and gold work. A possible reason for this is provided by the art historian Palomino in his "Museo Pictorico" of 1715-1724. He tells us that Valdés Leal, during his early training, also worked as a polycbromer of "retablos" and "rejas" (altar pieces and altar rails). He was therefore familiar with the elaborate decorative elements embellishing so much Baroque art.

In his "Virgin of the Silversmiths" (Museo Provincia de Bellas Artes, Cordoba), Valdés Leal gave free rein to his decorative ingenuity in the elaborate throne being offered to the Queen of Heaven. In all these early works (1644-1656) the artist also developed his personal vocabulary of color, characterized by delicate pastel shades and dulled tones: pale mauves, muted reds, faded yellows, misty silver greys, iridescent jade greens and leaden blues. It was likewise in Cordoba that he developed his technique of painting with a sparsely loaded brush and of using thinned paints, thus allowing one to see clearly the elaborate brushwork.

In 1656 the thirty-four-year-old artist returned to Seville to find a declining city abandoned by the silver fleets and the population decimated by the terrible plague of 1649.

In 1657-58 (the year that Zurbarán left Seville) Valdés Leal was commissioned to make a retablo for the Monasterio de los Carmelitas Calzados of Seville. Directly related to the “Saint Francis in Ecstasy”, on loan to the Museum, are the “Saint Michael” and “Saint Raphael” from this “retablo”. Both of these are based on Raphael's “Saint Michael” (Paris, Louvre), known to Valdés Leal through Giles Rousselet's engraving after the original. Raphael's “Saint Michael” was considered the paradigm of artistic excellence in 17th century academies, and it is therefore not surprising that Valdés Leal should have chosen to base his two archangels on this work.

Of interest to the student of Valdés Leal is the fidelity with which the artist has copied the weak and awkward placement of Saint Michael's left leg in his own figure. This flaw, not found in the original and unique to Rousselet's print, was not apparent to a painter unschooled in anatomy and unfamiliar with the nude human form.

The “Saint Michael” and the “Saint Raphael” also exhibit the delicate beauty and heavy-handed awkwardness typical of Valdés Leal. As in the “Saint Francis in Ecstasy” one observes the active postures and the flutterings of the draperies which serve to distract from the awkward proportions of the figures. These works also manifest elaborately wrought greaves, helmets and jeweled clasps.

In 1660 Valdés Leal was made "Diputado" or deputy of the newly formed Academy of Drawing in Seville of which Murillo and Herrera the Younger were elected joint presidents. At the high point of his career, he was also made "Alcalde de la Pintura" of the Guild of Saint Luke. It is during this period (1660-1665) that Valdés Leal produced his moving "Crucifixion" (1660-61) for the Church of the Magdalene and the "Saint Francis in Ecstasy".

The Saint Francis must have been designed for a "retablo", possibly for the church of San Francisco in Cordoba for which Valdés Leal had previously worked. It is the kind of painting normally employed as an altarpiece for a small devotional chapel. Originally it was placed above the eye level of the worshipper. Many of the distortions apparent in a head—on view therefore are corrected when the painting is seen at the proper angle from below.

Saint Francis was important to the Counter-Reformation as an alternative to the more militant saints of the day: Saint Dominic, Saint Carlo Borromeo, Saint Xavier, and Saint Ignatius Loyola. In return for the privilege of serving the church as a humble friar, Saint Francis had given up all worldly goods and, asking for nothing, had suffered Christ's agony and received the Stigmata. The treasures of this earth Saint Francis had willingly traded for the gift of eternal salvation.

The intense emotion and deep piety of Valdés Leal's "Saint Francis" is informed by the spirit of the Counter-Reformation. He is shown not, as was usual in earlier times, at the moment of receiving the Stigmata, or as the gentle preacher to birds and beasts, but in pious ecstasy as he meditates on the sacrifice of Jesus Christ. The source of his piety the New Testament, lies at his feet. Its pages as well as the features of the saint and angels are suffused with an unearthly glow. Draped over the book is the scourge with which he has been flagellating himself in penance for Christ's agony.

The more immediate object of his devotion is the Crucifix. The saint's lips brush the knees of the crucified Christ as if to warm the pitiful figure with his breath. Christ's pain is made evident in the strained and outstretched arms. Saint Francis’ identification with the suffering of Christ is conveyed by his swooning expression, the tenderness with which his left hand supports the Crucifix and by the mark of the Stigmata breaking the flesh of his right hand. He is ecstatic in veneration and in his complete absorption in the agony of Jesus, the saint's features assume those of the Christ in Valdés Leal's "Crucifixion".

The saint, a mere mortal man, is supported by two angels who, as the emissaries of heaven, are both larger than he. The outsize angel at the left, whose size would have been diminished when viewed from below, confronts the viewer, inviting him to contemplate the saint whose back he touches with a graceful, delicate hand. With his severely compelling gaze, this angel is one of the most strikingly beautiful elements in the painting.

The angel at the right, his forehead drawn with concern, swoops forward to catch the swooning saint. The body of this angel, bent at a ninety-degree angle, is masked by his cloak. His left leg thrusts forward and serves to lead the eye of the viewer back and up into the picture plane.

The dynamic composition of this painting is "Baroque" in its complexity. A strong diagonal, from lower left to upper right, is created by the figure of the Saint and the supporting angel. This is counter-balanced by the stabilizing vertical of the angel at the left. The picture plane is defined by the still life created by the rock, the book and the scourge (which serve as a "repoussoir"), and by the foot of the angel at the right. Recession is measured by the wings of the angels while the landscape framed by the triangular space between the saint and the supporting angel effects a sudden jump back in depth.

The "Saint Francis in Ecstasy" is a completely affective work filled with controlled intensity. An excellent example of Valdés Leal's painting, it is a superbly Spanish piece and typically High Baroque.

Valdés Leal's late period (1666-1690) was one of both artistic triumph and decline for the painter. In 1664 the dogma of the Immaculate Conception was adopted in Spain, and Seville became the center for the production of official images. As a subject matter, however, the Immaculate Conception was better suited to Murillo's tender sweetness than to Valdés Leal's more somber and dramatic talents. His late renditions of this theme are decidedly inferior to his earlier production. Fortunately, Valdés Leal found another subject matter better suited to his temperament. He devoted himself to developing the "vanitas" still life in a uniquely Spanish manner. These terrifyingly beautiful still lifes brought his career to a glorious end, and today they are the works by which Valdés Leal is best known. The "Saint Francis in Ecstasy", however, serves to remind us of the equally expressive power of his earlier art.

- Felipe Cervera, University of California at Santa Barbara, in SBMA Gallery Notes, v. 4 n. 1, July, 1979

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anonymous. Valdés Leal, Spanish Baroque Painter, New York, Hispanic Society of America, 1960.

Gestos y Perez, José. Biografia del Pintor Sevilliano Juan de Valdés Leal, Sevilla, Oficina Tipografica de Juan P. Girones, 1916.

Lopez Martinez, Celestino. Juan de Valdés Leal, Sevilla, Imprenta y Libreria Sobrino de Izquierdo, 1922.

Pacheco, Francisco. Arte de la Pintura, Madrid, Instituto de Valencia de Don Juan, 1956.

Palomino de Castro y Velasco, Acislo Antonio. El Museo Pictórico y Escala Òptica, Madrid, M. Agular, 1947.

Trapier, Elizabeth du Gue. Valdés Leal, Baroque Concept of Death & Suffering in His Paintings, New York, Hispanic Society of America, 1956.

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

In the wake of the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century, the Catholic Church placed an even greater emphasis on devotion to the saints as examples and intercessors for the faithful. Of these saints, there was probably none more popular than the Italian Francis of Assisi (1181– 1226), founder of the Order of Friars Minor (Franciscans). Francis renounced his wealth in favor of a life of austerity, preaching, and ministering to the poor. Even while still living, he was considered by many to be a “second Christ.” Francis assumed Christ’s Passion through the stigmatization, a visionary experience in which the saint received the same hand, foot, and side wounds (stigmata) that Christ suffered on the cross.

Toward the end of the 16th century, a new subject was invented: Francis in ecstasy, supported and consoled by an angel after the stigmatization. The subject may have been first introduced by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio in a canvas painted in Rome ca. 1595–1596, now in the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut.

The popularity of the subject of Saint Francis supported by an angel soon waned, although Franciscan subjects in general remained common in Italy, as well as in Spain, where devotion to the saint was just as fervent. More than a half century after the initial spate of versions of the subject, the Sevillian artist Juan de Valdés Leal painted the canvas exhibited here.

In Valdés Leal’s version of the subject, a large book—presumably the Bible—is propped against a rock in the foreground. According to Bonaventure’s account of the stigmatization, during Francis’s forty days of fasting and prayer, his companion, Brother Leo, opened the Gospel book three times in honor of the Trinity. Each time the book opened to an account of Christ’s suffering and death on the cross, and “the man filled with God understood that just as he had imitated Christ in the actions of his life, so he should be conformed to him in the affliction and sorrow of his passion.” Valdés Leal has excluded Leo from the painting, focusing the viewer’s attention on Francis’s intense experience.

- Ludington Court Reopening, 2021