Unknown

Ancient Gandhãra, present-day Pakistan

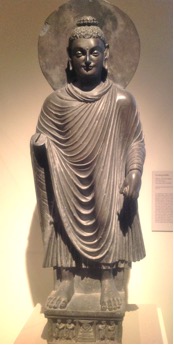

Standing Buddha Shakyamuni, 2nd c. CE, or 3rd

grey schist, face retouched

41 1/2 x 14 x 7 1/2 in.

SBMA, Gift of the Joseph and Barbara Krene Family Trust

2003.22.1

"Is it not as though the Hellenizing master-craftsman, whose skillful chisel-cuts produced this Buddha image from a block of blue schist, had left his own thoughts imprinted on the stone? Standing before his finished work, we think we understand how he conceived it and why he executed it in such a way. For one matter, had he not something of us in him, with the result that it is easier for us to read his thoughts? For another matter, do we not know in advance what those who ordered the images would have suggested to him? When they encountered the figure of the Buddha, he was not just fading in the mists of the past; he was rather beginning to lose his clear outlines in the clouds of incense that everywhere arose towards his divine nature now being realized. So after all, what one needed to represent was someone like a young prince, a descendent of the solar dynasty and more glorious than the day, who in former times, filled with loathing for the world and compassion for living creatures, had assumed the garb of a monk and had become by the power of his intellect a kind of savior god...

'Apollo, Saviour God, God of mysteries so learned,

God of Life and God of all salutary plants,

Divine conqueror of Python. God triumphant and youthful...'

Remembering these fine ancient verses of André Chénier (Bucoliques, VI), no one would be surprised that our artist should have thought at once of using as his model in such circumstances the most intellectual of his own youthful Olympian gods."

Alfred Foucher, L'art gréco-bouddhique du Gandhāra, vol. 2, p. 283. Trans. David Snellgrove.(Snellgrove, 71)

RESEARCH PAPER

At the beginning of the Common Era, in a remote region straddling the border between modern day Afghanistan and Pakistan, there flourished a culture that was a singular blend of the Greco-Roman and Indian worlds. Today, the only significant surviving evidence of this unique civilization is a body of stone sculpture that includes SBMA's Gandhāra Buddha. Although the Ghandāran language, people, and civilization are now lost to time, its body of sculpture not only reminds one of the existence of this almost forgotten people, but, more importantly this body of sculpture represents the beginning of the now widespread practice of the iconic veneration of the Buddha and the emergence of Mahayana Buddhism. (Samad, 172; Geoffroy-Schneiter, 18; Behrendt (2007), 47-50). The veneration of the Buddha began at the far western reach of Buddhism precisely because this region was at the edges of both the Buddhist and Hellenistic milieus and linked the two by one of the southern routes of the Silk Road. Despite its remoteness, Gandhāra was a hub of travel between the eastern and western worlds from the 4th Century BCE when Alexander the Great passed through on his ill-fated adventures in India, to when Marco Polo passed though in the 13th Century CE in his quest to rediscover China. (Geoffroy-Schneiter, 7).

Gandhāran Buddha images began the tradition of Buddha visual iconography that would become standard throughout the world today. The SBMA Buddha is surrounded by a halo that the Gandhārans probably borrowed from the depiction of Near Eastern and Zoroastrian sun gods (Leidy, 37; Samad, 177; Tresidder, 220). Buddha's hair is arranged in a topknot that covers his ushnisha. And, although the ushnisha or head bump is one of the thirty two physical marks, or lakshanas, of a holy man as described in the pre-Buddhist Indian Lakshana Sutra text, the wavy hair is borrowed from the Greco-Roman sculptural tradition (McArthur, 95, 97; Snellgrove, 67). The hair may also be styled to resemble the eternal flame of Zoroastrianism (Samad, 176). The urna, or third eye, is carved in relief. Its origin is also from the Lakshana Sutra. The half closed, almond shaped eyes are a Gandhāran innovation that would become the standard depiction of the Buddha's eyes. (Samad, 174). The elongated ear lobes derive from the Buddha's princely upbringing where he would have worn heavy earplugs that would have stretched his ears.

The now missing right arm and hand of the SBMA Buddha most likely formed the "fear not" Abhaya Mudra. In the Abhaya Mudra, the right arm is pointed up with the palm forward. The Buddha's left hand is holding his robes. The drapery is heavy and thick and covers both shoulders. The fluidity and opaqueness of the drapery of the Gandhāran Buddha images is of Greco-Roman tradition. Likewise, the bent right knee in the otherwise soldier-straight figure may be the artist's unsuccessful if quaint attempt at Greek contraposto; or this stance, often but not always seen in standing Gandhāran Buddhas, may be an iconographic characteristic of Buddha the meaning of which has not survived.

The base of the SBMA Buddha features four figures, two on each side of a central mound-shaped object sitting on a pedestal under an awning. Unfortunately, the central object is damaged and cannot be clearly identified. The object could be a seated Buddha, an image of Buddha's begging bowl, or a reliquary, a container that is used to hold holy objects called relics. It is possible that the central figure is Buddha sitting in the lotus position but if so, Buddha's neck is abnormally thick. Buddha's begging bowl is usually depicted flat on top and rounded on the bottom and is therefore also difficult to reconcile with the shape on the base. The most likely explanation of the central figure is that it depicts a relic being worshipped by four devotees. Faxian, a Chinese pilgrim who visited Gandhāra in the 4th-5th Centuries CE described the presentation of a skull bone relic at Hadda: "They place [the relic] ...on a high throne...the stand is placed below [the relic], and a glass bell as a cover over it. All these are adorned with pearls and gems." (Behrendt, 86) Behrendt further states "narrative reliefs depicting cloth-covered bell-shaped reliquaries on thrones provide supporting evidence for Faxian's description." (Behrendt, 86). The shape of the central panel on the base of the SBMA Buddha corresponds exactly with the description of Faxian and Behrendt of a reliquary shrine. It has a square base supporting a bell shaped object covered with a cloth structure.

The SBMA Buddha is made of grey schist, a locally available stone whose suitability for fine carving varies considerably. Schist is found in shallow beds and breaks away in thinner slabs rather than in blocks, making it impossible to carve larger sculptures completely in the round from a single piece of stone. (Penny, 103). The SBMA Buddha is formed from a flat slab. The back remains flat and the features of the statue are carved away from the solid slab only from the front. The Buddha's right raised arm would not have been able to be carved from the flattened slab and thus was pieced from another stone. The limiting characteristics of schist, the only locally available stone suitable for large scale carvings in the Gandhāra region, rather than artistic expression, is the most likely reason that Gandhāran art developed the serene, flat, calm beauty so different from the more flamboyant marbles of Greece and Rome or the voluptuous, rounded sandstone figures of southern India both traditions that any good Gandhāran artist would have been familiar with.

The SBMA Buddha would have been gilded with gold or silver leaf. (Behrends, 82-83; Samad, 148: Penny, 103). Small pieces of gilding, and sometimes an underlayment of red priming can still be seen on some Gandhāran art. One can also assume that Gandhāran Buddhist shrines and reliquaries, and their attendant Buddhas, were places filled with colorful worshippers, offerings, incense, and flowers just as in modern Buddhist temples.

Buddhist missionaries first made their way to Gandhāra from India under the religiously tolerant Achaemenid Empire of Cyrus the Great and his descendants who ruled Gandhāra between 535 BCE and 326 BCE. (Samad, 31-35) However, it was the Indian regent Ashoka of the Maura dynasty in 274-232 BCE who was responsible for making Buddhism the supreme cultural force in Gandhara for over 700 years. (Marshall, 7). In a benevolent act, Ashoka disinterred and divided the Buddha's remains to new sites throughout his realm. Ashoka sent remains to three locations in Gandhāra covering Buddha's remains with mounds of earth. After Ashoka's death, elaborate and numerous stupas, dome shaped mounds or buildings holy to Buddhists and often containing relics, and sangharamas, or monasteries, were built over and around Ashoka's original mounds, to venerate Buddha's begging bowl that tradition says was brought to Gandhāra, and to venerate the remains of other Buddhist religious figures. (Samad, 49) Statues such as the SBMA Buddha were devotional icons commissioned to be placed in niches as adornments to a Buddhist reliquary shrine or stupa. (Behrend, 81-82; Samad, 143-167).

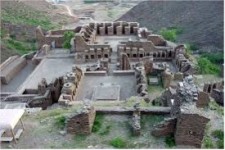

Statues like the SBMA Buddha were usually sculpted by a local artisanal workshop and bought by a religious pilgrim as an offering. The SBMA Buddha was intended to be ensconced in a wall or cliff-side niche or was part of a building facade. The back of the Buddha was not only left un-modeled but the schist was also scored to create a roughened surface to better attach it to a wall with mortar. In the photograph of Takht-i-bahi, Pakistan, below, the best preserved Gandharan sangharama and now a World Heritage Site, one can see the large square base that would have held a reliquary stupa. The surrounding niches would have held devotional icons such as the SBMA Buddha.

Ghandāran art was discovered by Europeans in the late 1830s during the First Anglo-Afghan War. British soldiers, treasure hunters and professional archaeologists alike removed art and coins with little proper documentation. Pieces such as the SBMA Buddha can no longer be tied to their original context and location and therefore cannot be accurately dated using scientific means. However, epigraphic evidence on some sculptures combined with comparative dating using the few pieces that have been found in situ have allowed experts to approximate the dates of Gandhāran art by comparing their features. Using this methodology, SBMAs Buddha probably dates from the 2nd or 3rd centuries of the Common Era. Juhyung Rhi, a South Korean scholar of Gandhāran art, has recently proposed a new categorization technique of the corpus of Gandhāran Buddha images using visual characteristics. Rhi has broken the Buddha statues into five types--Type I through Type V--based solely on selected visual attributes. This research is in its infancy and cannot yet be used to date images. Rhi would probably consider the SBMA Buddha to be a Type V icon because of its lack of incised mustache, lack of low ridge drapery folds, flat abdomen and the possibility that the base scene is that of the veneration of a reliquary. (Rhi (2013), 69-73).

The SBMA Buddha is remarkable for both its beauty and its good condition but it is certainly not unique. Gandhāran Buddhas can be found in many major museums and on the private market simply because so many of them were made. The Chinese writer and traveler Hsiuen Tsang spent 19 years in Gandhāra during the 6th Century, after the White Huns had destroyed much of Gandhāra a century before. Hsiuen reported that there had been 1,400 sangharamas and 18,000 monks on the Swat River alone although most of the sites were in ruins and few monks remained by Hsiuen's time. (Samad, 140) Because many devotional Buddhas surrounded each stupa, and each sangharama had at least one stupa, there must have been many thousands of such Buddha statues made.

Gandhāran Buddhism and its associated art have been slowly destroyed and looted beginning with the invasion of the White Huns in 463 CE and culminating with the deliberate destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas in February 2001 by the Taliban. With such a tragic history, it is wonderous that in this remote land, so many stone statues which seamlessly blend the best of the east and the west were made and survived long enough to be dispersed throughout the world. Gandhāran academic Mario Bussagli eloquently gives Gandhāran art its due when he writes "The history of the extraordinary adventure of Greco-Hellenic art harnessed in the service of the Buddhist Word, is a story of adaptation, modification and transformation. Of metamorphosis, one could even say." (Geoffroy-Schneiter, 17).

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council

by Molora Vadnais,

February 1, 2014

Bibliography

Asia Society, http://sites.asiasociety.org/Gandhāra/exhibit-sections/buddhas-and-bodhisattvas.

Behrendt, K. A. The Art of Gandhāra in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007.

Behrendt, Kurt A. and Pia Brancaccio. Gandhāran Buddhism: Archaeology, Art, Texts. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2006.

Geoffroy-Schneiter, Berenice, Gandhāra: The Memory of Afghanistan. New York: Assouline Publishing, 2001.

Leidy, Denise Patry. The Art of Buddhism. Boston & London: Shambhala, 2008.

Marshall, Sir John. The Buddhist Art of Gandhāra. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, 2008.

McArthur, Meher. Reading Buddhist Art. London: Thames & Hudson, 2002.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/kush/hd_kush.htm.

Norell, Mark, Denise Patry Leidy, & the American Museum of Natural History with Laura Ross.

Traveling the Silk Road. New York: Sterling Signature Publishing, 2011.

Penny, Nicholas. The Materials of Sculpture. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1993.

Rhi, Juhyung, Identifying Several Visual Types in Gandhāran Buddha Images. Archives of Asian Art,

Vol. 58, pp. 43-85. 2008.

Rhi, Juhyung. “From Bodhisattva to Buddha: The Beginning of Iconic Representation in Buddhist Art.

”Artibus Asiae 54, no. 1/2 (1994).

Samad, Rafi-us. The Grandeur of Gandhāra: The Ancient Buddhist Civilization of the Swat, Peshawar,

Kabul and Indus Valleys. New York: Algora Publishing (2011).

Snellgrove, David L. ed., The Image of the Buddha. New York: United Nations Educational, Scientific

and Cultural Organization (1978).

Tresidder, Jack, ed., The Complete Dictionary of Symbols. San Francisco: Chronicle Books (2004).

Takht-i-bahi, Pakistan, below, the best preserved Gandharan sangharama and now a World Heritage Site, one can see the large square base that would have held a reliquary stupa. The surrounding niches would have held devotional icons such as the SBMA Buddha.

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Buddha’s enlightened serenity is characteristically expressed through his introspective composure and the halo behind his head. This figure exemplifies the distinct blend of Buddhist iconography and Hellenistic-influenced facial features and drapery in the region of ancient Gandhara (modern-day Pakistan and Afghanistan). Once the crossroads of Asia and the Middle East, Gandhara was also one of the first regions in India where figural representations of the Buddha emerged.

- India, Southeast Asia, and Himalayas, 2022

Draped in a voluminous shawl the end of which he holds in his left hand (the right forearm was separately attached), with a panel on the base depicting devotees approaching the enshrined relics of Buddha.

- Puja and Piety 2016