Unknown

Russian (active Novgorod School)

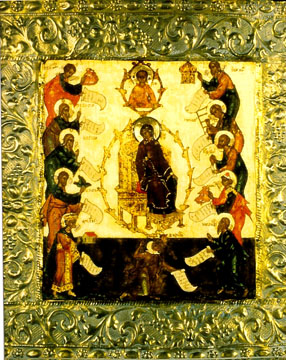

The Exaltation of the Virgin, 1500-1550 ca.

egg tempera on wooden panel and attached silver basma

12 x 10 5/8 in.

SBMA, Anonymous Gift

1961.5.5

RESEARCH PAPER

The icon in the context of Russian history, culture, and religion has had a fractured life. The word derives from the Greek word for image but in Russian use, has come to mean sacred image. The sacred images generally fell into several categories: Images of Christ, of the Virgin and Christ Child, Festival Scenes from the Orthodox Church tradition, Old Testament Subjects, and Icons of popular Saints. Our Exaltation falls into the second category. Throughout their history, icons have been used on choir screens, or iconostasis, in the Orthodox Churches, on the tombs of saints and martyrs, and in private homes. They have appealed to every level of devotion from the simple peasant to the most sophisticated theologian.

In the Russian Church, Mary is exalted above all the saints and is at the absolute top of all celestial hierarchies. This exaltation is recognized by the word, “hyperdulia”, and Webster’s dictionary term for the homage paid to the Virgin Mary, because Mary is holier than any other human being.

The Santa Barbara “Exaltation of the Virgin” is a fine example of this theme. In composition and style it is close to a late 15th century version now in a gallery in Moscow. However, the Santa Barbara version, although employing the resplendent gold background, lacks the brilliance of color found in the Moscow version and the identity of the prophets arranged along the sides is not the same.

VISUAL ANALYSIS

The icon is the prime expression of Russian religious thought and popular piety. Its window-like vision into another mystical world seems at first naïve and unsophisticated, but upon further study reappears with an abstract and subtle composition.

The Virgin Mary is seated on a throne wearing a deep red “maphorion” or long veil covering the head and shoulders, her right hand is raised with palm extended and her left hand rests on her knee. She is shown with head bowed to humility. A floral wreath surrounds her and extends upward to frame a bust of the youthful Christ who is holding a scroll and who is blessing the Virgin. Both of the figures have attached silver halos. The figure crouching below the Virgin’s footstool is Balaam, one of the Old Testament prophets. Balaam is holding a scroll. Directly above him and just below the Virgin’s footstool is a symbolic star.

Eleven Old Testament prophets surround her, some of which are holding richly symbolic attributes which can be interpreted as theological references to Mary. They are Habbakuk, holding a mountain; Jeremiah; Isaiah; Moses, holding a bush; King David, with the synagogue; Balaam, with a star; Ezekial with the Royal Door; Jacob, holding a ladder; Gideon holding the fleece; Daniel, with a mountain, and Hosea. The prophets are shown in column style starting with the upper left corner. The 4th prophet is Moses shown with the burning bush that he saw in the Wilderness; the bush is a symbol of Mary’s virginity. Jacob, the 2nd prophet on the right side is shown with the Ladder to heaven; Mary has been referred to as the Ladder. The same holds true for the Royal door, shown with Ezekiel, the 1st prophet on the right side.

The silver border with floral decorations adds a sumptuous note that almost competes with the visual importance of the painting.

Discussion of technique

Early icons were never intended as historical document or works of art. The earliest icons were painted using an encaustic technique which utilized pigments dissolved in melted wax and applied with a knife. Few colors were used in earlier icons. Later ones used 8-10 vegetable or mineral pigments. The manner of detailing the icon features differentiates the later from the earlier works in expressiveness especially in the eyes, density of colors, softness of outlines, quality of shading and highlights, folds of garments, contours of hills, and outlines of buildings. Gold was used in later works for highlights. Precious materials and gems were regularly used in the frames and covers. It would be hard to overemphasize the role of religious and monastic tradition in the standards for decoration.

In the case of contemporaneous works about the time of our Exaltation, a non resinous wood such as cypress or birch is dried. Struts are built into the back to deal with warping. The front is cut out to create a raised frame. The front surface is roughened and covered with a liquid sizing. Loosely woven linen is glued to the sized surface. The surfaced is resized and allowed to dry. An outline drawing is sketched on the surface in pencil or brush. The drawing derives from a manual of acceptable images. The contours of the drawing are etched into the sizing with a sharp instrument. Gold leaf, if used, is applied at this point. Pigments are prepared from egg yoke and pigment and mixed with a little vinegar as a preservative. The pigment is applied and allowed to dry for several days. Finally a boiled linseed oil is applied to the entire surface. The linseed oil protects and brings out a richness and translucency to the colors.2

Information about the similar works during the same time

Western European panel paintings have always been sought by collectors, particularly those works from Italy. The progressive ideas so well known in Western Europe find no such tradition in Russia works due in part to the fact that Russia was virtually isolated from Western Europe from the 11th to the 17th C’s. Russian panel paintings are rarely acquired or exhibited, and provenance of Russian art has always been confusing and unclear.

As in Western medieval art, Russian monastic artists who painted remained anonymous. Since the works were intended to be channels of divine inspiration, the creative personalities were not intended to enter into their creations.

A few Russian icons date as early as the 11th and 12th C’s. The earlier icons were defined by the art school that surrounded Constantinople. Two artistic styles seem to predominate during the 15th and 16 C’s.

About the start of the 14th C, the iconographic style grew into what has been called the Novgorod School, represented by our Exaltation. This style was a mix of the Russian and Greek albeit with a special composition, rhythm and color. Lines were long and straight; figures usually short, 7 to 7 ½ heads in height, faces were long with noses that tended to droop over the mouth. Robes were generally painted in two colors, or outlined in thick lines of black or white. Fine white lines surrounded the eyes, the forehead and nose. Joints of hands and feet were outstanding attributes. Flesh tones were dark brownish or bluish-green.

Icons from the first of 16th C show greater freedom, and illustrate scenes from literature, social matters or history, rather than being simply graphic. The Stroganov School or style was born about 1580 about the time of our icon. The Stroganov style emphasized the smaller sizes important for cramped family chapels but was still elaborate and decorative, and had the characteristic of miniature works. Enlargements would have resembled large compositions.

Pertinent dates and events in history which provide context for the work

The cult of sacred images evolved in the 4th C in and around Byzantium when the Christian Church began to reflect the divisions in the Rome based church. At that time, Constantine the Great moved the Roman capital east to Byzantium, the city that was to bear his name, Constantinople. The bishop in Rome however, continued a Western tradition, culminating in an official break between the two branches in 1054. In the Byzantine or Eastern Church, images replaced relics as sacred objects, but conservative clergy declared a war on images based on their interpretation of the Mosaic commandment regarding graven images. This led to an Iconoclastic or “image beaker” period for about 100 years dating from 726 AD. Fortunately for the history of art, “image worshippers” won out over the iconoclasts during the 9th C when it was argued that icons emphasized the visible link leading man to God. This period lasted until the 13th C when Western Europeans took possession of Constantinople during the 4th Crusade. Byzantine artists fled the capital seeking employment in areas in which the Orthodox Church still had control. The Byzantine Empire collapsed until the 15th C when Turkish forces reoccupied Constantinople.

A major series of events in the 16th C affected the history of the icon. Ivan IV (The Terrible) had assumed title of the region that included Moscow. A major fire in Moscow during Ivan’s reign contributed to Moscow’s concentration of artistic activities. Following the fire, Ivan, with a flair for art, and the Orthodox leaders emptied the churches throughout the South to refurnish the churches around Moscow. The Orthodox Church moved north and Moscow became its center in 1589….which brings us to the time frame for our Exaltation.

Theological literature impacting the creation of icons became contrived, complex, and scholastically abstract. In 1551, a council of religious leaders was created to deal with Tsar’s questions to the Church. Among other things, the Council proclaimed that “You must watch with the greatest care that the icon painters have irreproachable sentiments and practice virtue, that they instruct pupils and teach them to paint divine images with skill and according to consecrated types.” Icon painters “should be meek, mild and pious, not given to idle talk or laughter, not quarrelsome or envious, not a thief or murderer…be slow to independence”4

Icons suffered through the centuries from preservation techniques. The more the icon was revered, the more it was re varnished…up to 6 coats of paint. There was no preservation or restoration until the 1917 revolution

IN SUMMARY…

The Exaltation of the Virgin icon was one of 12 Russian icons presented to the SBMA as an gift from an anonymous donor who was a diplomat in Russia in the late 30’s The works were thoroughly researched, restored and catalogues prior to a 1982 exhibit at the Museum entitled Windows to Heaven.

Robert Henning said it so well in Russian Icons in the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, “Seen so far removed from their original settings, icons nevertheless have an intrinsic power of expression and sheer beauty of pattern that transcend historical, cultural, and religious contexts to speak to us directly as works of art.”

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Bunt, Cyril G.E.. A History of Russian Art. The Studio, London and New York, 1946

2. McKenzie, Dean. Russian Icons in the Santa Barbara Museum of Art. Santa Barbara, California, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, c1982

3. Windows to Heaven: The Icons of Russia. Santa Barbara, CA, Santa Barbara Museum of Art,

c1982

4. Weitzman, Kurt et Al., The Icon, Alfred Knopf, New York, 1982

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Charles B. Thompson, October 2005