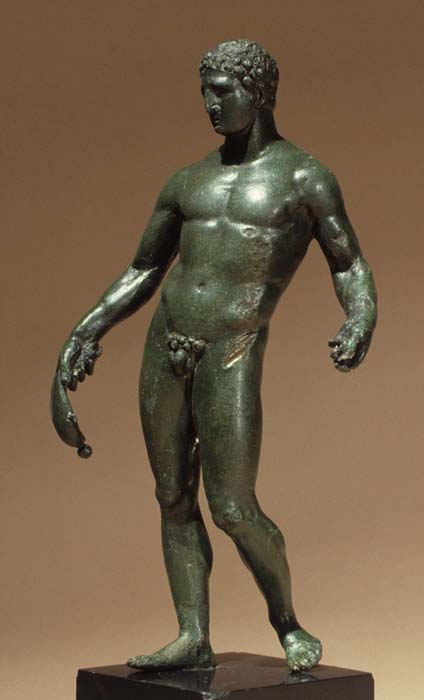

Unknown

Roman

Hermes, 1st c. BCE, late - early 1st c. CE

bronze

6 1/2 x 3 1/4 in.

SBMA, Gift of Wright S. Ludington

1981.64.19

RESEARCH PAPER

Pelvis thrust forward in a languid pose some two millennia before Elvis, his weight firmly on his leading right leg even as his torso arcs in a backward lean, he is balanced more by his suggested forward movement than his just barely ground grazing trailing left foot.

Our bronze statuette’s somewhat rakish and sensual pose suits its subject well. Hermes, the gods’ messenger, may have been the ancient Greek god of trade, wealth, luck, fertility, animal husbandry, sleep, language and travel, and the guider of souls to Hades across the River Styx, but he was also the god of thieves and pranksters, one of the most mischievous and colorful of the Olympian gods (when, as a baby, he stole his half-brother Apollo’s sacred herd of cattle, he reversed their hooves to make it difficult for those trying to follow their tracks), and so it’s reasonable to associate his raffish character with the somewhat provocative pose of our modestly sized bronze.

The graceful form with its lithe pose also provides clues to its dating and influences. It celebrates the male form of course, reflecting the high value the Greek (and subsequently the Roman) civilizations placed on the beauty of the (correctly) proportioned naked body, but also places the probable influence of the work in the late Classical period; for not only is the naturalistic (though idealized) form balanced on a graceful contrapposto, the contrapposto itself is extreme, thrusting the figure expressively forward into space. Movement is not simply suggested by a natural but static pose, the form is in fact projected forward in a grand arc, and that curve is echoed and amplified by that of the money pouch (1), which itself, through its gentle form continues and elongates the graceful curve of the arm, and through its inertial pendular motion adds to the suggestion of overall movement. The left arm in turn extends backward, mirroring the line of the trailing left leg, and lending balance to the overall form.

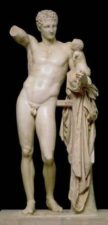

Roman sculptures were typically either stylistic derivations or outright copies of Greek originals. Numerous such pieces (particularly of Hermes) can be associated with the works of Polykleitos (active 450-420 BCE), but Polykleitan types, although naturalistic, counter-posed and graceful, are too static to be the inspiration of this Hermes. We might look rather to Praxiteles (active mid-4th century BCE) as a more likely influence. A good Praxitelean analogue to our bronze is his (attributed) Diana of Gabii, which exhibits a similar graceful movement, down to the raised left heel and just barely ground grazing big left toe.

It is easy to imagine this sensually exquisite piece as a decorative object existing only for the pleasure and display of wealth of a class conscious Roman, and it almost certainly was that, but there is evidence, such as in writings of Pliny the Younger, that decorative pieces and statuettes could also be used as votive objects, and even sometimes offered to temples as gifts. We don’t know what specific functions this particular statuette may have served in its two thousand year life but we are fortunate that it has made its way to our collection.

Notes:

(1) Hermes (Mercury, to the Romans) can typically be depicted holding the “kerykeion” or staff (signifying his role as a herald), wearing winged sandals and/or the winged cap (“petasos,” symbolic of his role as a messenger), a long tunic for travel, and a money pouch, signifying his association to commerce, wealth, and luck. The Hermes of our statuette does not hold the characteristic staff, nor is he wearing the even more characteristic winged cap or sandals, but is very prominently grasping the money pouch.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Marcos Christodoulou, 2020.

Bibliography

Kaufmann-Heinimann, Annemarie. “Function and Use of Roman Medium-Sized Statuettes in the Northwestern Provinces.” J. Paul Getty Museum.

http://www.getty.edu/publications/artistryinbronze/statuettes/18-kaufmann/#fn:4

Barr-Sharrar, Beryl. “Assertions by the Portable: What Can Bronze Statuettes Tell Us about Major Classical Sculpture? ” J. Paul Getty Museum.

http://www.getty.edu/publications/artistryinbronze/statuettes/13-barr-sharrar/

Del Chiaro, Mario Aldo. “Classical Art: Sculpture.” Santa Barbara: Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1984, p. 9.

Janson, H.W. “History of Art.” New York City: H.N. Abrams; 4th edition, 1991, p. 193

Praxiteles - Hermes

COMMENTS

Hermes (Roman name: Mercury) was the ancient Greek god of trade, wealth, luck, fertility, animal husbandry, sleep, language, thieves, and travel. One of the cleverest and most mischievous of the Olympian gods, he was also their herald and messenger. …

Noted for his impish character and constant search for amusement, Hermes was one of the more colorful gods in Greek mythology. While still a baby he stole his half-brother Apollo’s sacred herd of cattle, cleverly reversing their hooves to make it difficult to follow their tracks. Hermes therefore became associated with thieves and he kept the stolen herd in return for giving Apollo his lyre. …

In ancient Greek Archaic and Classical art, Hermes is [often] depicted holding the “kerykeion” or staff (signifying his role as a herald, the stick is either cleft or with an open figure of 8 at the top), wearing winged sandals (symbolic of his role as a messenger), a long tunic, sometimes also a winged cap (“petasos”), and occasionally with a lyre. …

https://www.ancient.eu/Hermes/

In the Classical period, the fifth and fourth centuries B.C., the striving for perfection in rendering the human form, both male and female, continued and reached its peak in the works of the great masters, Myron, Pheidias, and Polykleitos in the fifth century, and Skopas, Praxiteles, and Lysippos in the fourth century. Because nearly all original work of these masters has been lost, our knowledge of them comes from primarily literary references, as in Pliny and Pausanias, and from the many copies and versions of the originals that were produced in later, chiefly Roman, times. Though we may regret the loss of the originals, we are thankful that the Romans were not unsympathetic to the art and culture of the Greeks whom they conquered. The Roman legions bore the statuary and other works of portable art back to Rome, and Romans soon developed an insatiable appetite for Greek art to adorn their palaces and villas. The result was a wholesale copying of Greek statues, many of which would otherwise now be only names recorded by Greek and Roman writers.

- Mario A. Del Chiaro, Classical Art: Sculpture, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1984, p. 9

[The pose of our Hermes bears a resemblance to one of Praxiteles’ most famous works.]

A more faithful embodiment of Praxitelean beauty is the group of Hermes with the infant Bacchus at Olympia; it is of such high quality that it was long regarded as Praxiteles’ own work. Today some scholars believe it to be a very fine copy made some three centuries later. The dispute is of little consequence for us, except perhaps in one respect: it emphasizes the unfortunate fact that we do not have a single undisputed original by any of the famous sculptors of Greece. Nevertheless, the “Hermes” is the most completely Praxitelean statue we know. The lithe proportions, the sinuous curve of the torso, the play of gentle curves, the sense of complete relaxation, … the faint smile, the meltingly soft, “veiled” modelling of the features; even the hair, left comparatively rough for contrast, shares the silky feel of the rest of the work.

- H. W. Janson, History of Art, 4th Ed., 1991, p. 193