Unknown

Egyptian-Fayum, possibly from Er Rubayat

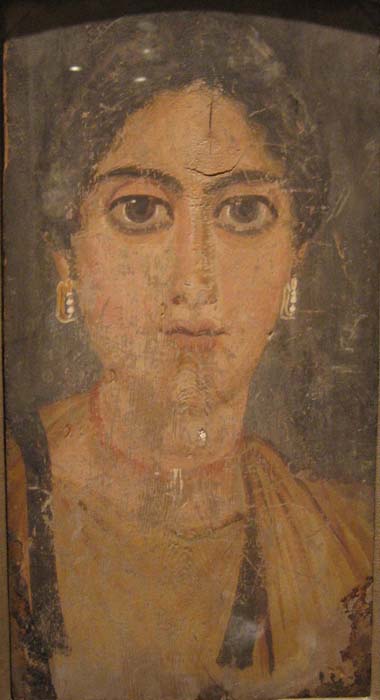

Mummy Portrait of a Woman, 3rd c. CE, late

tempera on wood

SBMA, Gift of Wright Ludington

1959.19

RESEARCH PAPER

Though this portrait of a elegant middle aged woman is very old, it is timeless. When you look at the sparkle in her eyes or the moisture of her skin, it seems she is both here with us and she can take us back in time. The time is the 3rd Century A.D. in the ancient Egyptian town of Philadelphia located in the north of the Fayum region, about 200 miles up the Nile from Cairo.

Philadelphia was first settled by the Greeks under Ptolemy 11, but in Hadrian's time became a Roman Colony. Like the Nile Delta, the Fayum was a rich agricultural area where barley, flax, and sesame were grown, carried by caravan and shipped though Cairo to other ports around the Mediterranean. Sesame oil was as important a fuel then as oil is now. Despite the fall of the Holy Roman Empire, Philadelphia remained a major economic trade center: filled with merchants of many cultural backgrounds (Greek, Roman, Ethiopians, Jewish, etc.).

The Romans had adopted some of the customs of Egypt. One of these was mummification or preservation of the body at death. "The Ancient Egyptians believed that everyone had ...: the 'ka' or spiritual double, created at birth and released from the body at death; the 'ba' or soul and the 'akh' or supernatural power. As long as the body was preserved, the 'ka' and the 'ba' could live eternally." (#6 p 38)

In earliest times the face on the mummy casket was an idealized abstraction most often in the likeness of Isis or Osiris (ruler of the dead): a geometric image similar to the face of Ka'emwesset in our Museum. With the increase in numbers and diversity of population in this later period, the face on the mummy changed to be a portrait of the person. People wanted to make sure their "ka" recognized them in the afterlife.

Portraiture had been common in the Greek/Roman culture dating from as early as 3rd and 2nd B.C.. Polyblus (about 201 - 120 B.C.) describes the carrying of ancestral portraits of the deceased during the funerary procession (which still is common in smaller towns in Italy). A portrait like the SBMA funerary portrait would have been painted at some important point in a person's life: for their wedding or when they could afford it, and kept in the home the way we keep photographs or painted portraits. As the custom became more common, portraits were done of all types and ages of people and there was a varying degree of qualities and styles available. Upon the person's death, that portrait was wrapped into the final layer or attached directly to a painted cartonage which held the mummified body. The whole mummy cartonage would be kept in the house or the courtyard to serve as an ancestral shrine until that time when the person was no longer remembered or the casket was badly damaged. Then, it was taken and deposited in a grave at the "necropolis" or burial grounds.

These ancient Fayum portraits which are some of our earliest examples of painting were first presented in exhibitions in Europe in 1889 and in New York in 1893. They were part of a collection of over 300 funerary portraits brought by Theodore Graf, a famous Viennese antique dealer, in the 1880's by his Cairo agents. As he was an art dealer and not an archeologist, however, he did not scientifically record his findings so the portraits from this collection can not be precisely dated. Many of the funerary portraits, called “Fayum portraits” in this exhibition, were scientifically recorded and time dated. Through comparative studies of painting techniques and styles, and of the differences in jewelry and hair styles of the scientifically dated pieces, assumptions have been made as to the dates and probable origins of Graf's unknown pieces. And though these funerary portraits come from different regions, they are all often referred to as "Fayum portraits". (#1 p 128-132)

At first the SBMA Funerary or Fayum tempera on wood portrait was dated to the late 3rd C. E. and was believed to have been done by a Greek painter Apelles. He had produced at least two other portraits of similar style and they have been accurately dated as having come from the Er Rubayat necropolis (or burial grounds) and were part of Graf's collection. The current analysis of it places this portrait in the 4th century C. E. (#3).

Some attributes that distinguish the style of this painter from other Fayum painters are (1 ) the fine brush strokes which make the skin seem moist and lifelike; (2) the long thin line of the head and long neck juxtaposed against the dark background setting off the creamy skin color: letting the dark hair fade into it at top; (3) the tight cropping of the figure so that it dominates the whole board rather than leaving an equal margin of background all around the face as frame-- it puts the chin at the horizontal center line of the composition and the eyes in the center of the upper half and the line of the nose in the vertical center; (4) the clever turning of the head to the side of the body torso, the raising of the right shoulder, and dropping the left giving it a three dimensional shape; (5) the way the long thin nose is drawn; (6) the simple elegance or lack of extra adornment of the portrait: emphasizing the face rather than adorning the face; and (7) the large eyes and the particular way they are painted.

To paint her, first the artist selected a very thin piece of wood: about 1.6-2 mm thick. Usually the wood was sycamore because it was easy to bend and conform to the curved surface of the cartonage. Other painters chose cypress or even pine depending on the color they might want to make the skin or whether they were doing a male or a female portrait: often selecting darker woods for the males. At the corners of the SBMA portrait, there are places where the wood is chipped off showing where it was attached to the cartonage.

To prepare for the egg tempera or encaustic paint mix used in the Fayum portraits, the painter would have coated the wood in a mix of animal glues and gypsum (a white powdery earth substance). This was done to preserve and seal it so the paint would not bleed into the wood and to provide a white base that when it shown through the subsequent layers of paint created a glow to the skin making it seem moist. Next, a sketch was drawn: usually in black and then using the Greek four color painting technique (tetrachromy) the basic forms were colored on the portrait.

This SBMA Fayum portrait was painted in water based egg tempera: a water soluble medium made of a mix of pigments and egg yolks with animal glues, gums, and resins. The use of egg tempera, while considered less precious than the "encaustic technique" usually associated with the "Fayum portraits", allowed the painter to work quickly with brushes and to blend and maintain control of the brush strokes at all times. When it is done the surface is smooth.

In the SBMA Fayum, a dark blue black mixture was placed on the background and under areas where the hair would be: a khaki-green color was laid on the area which would be skin (visible on the lower neck/ upper torso where the subsequent layers have been chipped away): a yellow ochre tone for the thinner under-garment or tunic and a deeper burgundy red for the ribbon on the neck and around the cape that is laid over her shoulder. While the richness of this red color has faded, a little of the pinkish tint is left on the neck band.

Then using these four basic colors, the paint was applied with small strokes in a hatching like pattern and layered upon each other in an impasto technique to make a density that seems to sculpt the face. A bit of "cyclamen" pink was added as a blush to the cheeks. Finally, a dot of white was added to each eye: at that moment it seems to make her come alive: as if she is here with us. Perhaps she has transcended time.

There are many different styles in which the Fayum portraits have been painted reflecting the relative skill and speed with which the artist worked. As the adding of the portrait became a common part of the mummification practice not all people could afford an elaborate or carefully done portrait: some portraits were done on unprimed surfaces, in quick sketchy lines with simple unblended blocks of color while others are as rich and elegant as works of Rembrandt.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Best Sources and those quoted in text:

1. The Mysterious Fayum Portraits: Faces from Ancient Egypt. by Euphrosyne Doxiadis, New York, Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers; 1995.

2. "Egyptian "Fayum" Mummy Portraits" by Reilly P. Rhodes, Museum Director J. Paul Getty Museum. Malibu California, J. Paul Getty Museum Publication. 1978.

3 "The Artists of the Mummy Portraits" by David L. Thompson. Malibu, California: J. Paul Getty Museum Publication. 1976.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Gail Elnicky, September, 1997; edited by Marilou Shiells 2005; prepared for WordPress posting by Vikki Duncan 2012.