More on Eight Taoist Immortal Icons

Unknown

Chinese

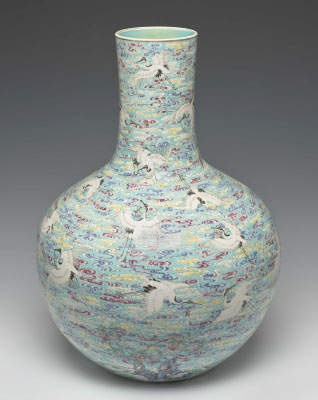

Vase with Flying Cranes amid Colorful Clouds over Islands of Peach Trees, 1735-1795, Qianlong mark and period

Jingdezhen porcelain painted with overglaze polychrome enamels

21 1/2 x 14 1/2 in.

SBMA, Museum purchase, funds provided by Friends of Asian Art, 1989

1989.47

A man rode off on a crane long ago

Yellow Crane Tower is all that remains

Once the crane left it never returned

For a thousand years clouds have wandered in vain

The trees of Hanyang shine in midstream

The sweet plants of spring overrun Parrot Isle

At sunset I wonder which way is home

Mist on the river only means sorrow

- Cui Hao 704-754 “Yellow Crane Tower”

RESEARCH PAPER

This large exquisite porcelain Chinese vase represents the height of ceramic art during the Qing (pronounced Ching) Dynasty. Start your visual journey at the bottom of the vase, looking in the mirror and spiral your way upwards noting the many images of immortality.

First you see that peach trees are growing on islands in a deep sea at the base of the bulbous vase. In Taoist folklore, this “Fairy Fruit” of the gods blossomed once every 3000 years, took 3000 years to ripen, and gave immortality to anyone who tasted it. Thus, peaches are associated with deities and longevity. They could be compared to the golden apples of Hesperides that gave the Greek gods immortality.

Thirty-one white cranes flying diagonally around the vase also represent immortality. The crane is thought to be the messenger of the gods and can carry immortals from place to place. The crane is a symbol of longevity also because its white feathers are like the white hair of wise ancestors, and cranes live a long life.

Each of the Flying Cranes carries in its beak a symbol of the “Eight Taoist Immortals” who are legendary beings in Taoism, described as actual people (including two women), and attained immortality through their moral living and spiritual understanding of Nature’s secrets. They each represent different dualities in life: poverty & wealth, aristocracy & common people, age & youth, masculinity & femininity. The immortals are spiritually immortal beings or physically immortal beings like shamans, wizards, genies, sages or hermits. In the vase each crane carries in its beak a different tool to prolong life: a fan, double gourd with iron crutch, fish drum, lotus, flower basket, sword with fly-whisk, castanets or a flute. Each symbol held by a crane represents longevity and embodies a different well-known moral tale associated with one of the Eight Immortals.

The background on the vase is covered with colorful “lucky” cloud motifs. The Chinese word for cloud is pronounced the same as the word meaning “luck or fortune.” The stylized cloud shape also resembles that of the lingzhi mushroom or “elixir of immortality” used in Chinese traditional herbal medicine. Clouds are considered a balance of opposites like yin and yang because they contain both water & air, or earth & sky. Clouds were often used as vehicles for a deity to move from one place to another, so clouds can prophesy the arrival of an immortal. And the colors represent the Five Chinese Elements in traditional Chinese medicine: red for fire, yellow for earth, white for metal, blue for water, and green for wood.

Porcelain is so associated with China that we call it “china” in English. This renowned clay body is made of white clay (kaolin) mixed with china stone (petuntse or crystals of potassium, sodium, and calcium) that vitrifies at 1400*C or 2600*F. The Chinese perfected porcelain hundreds of years before any other country and it was prized everywhere because it is extremely strong, yet thin and translucent, more hygienic and easier to clean than wood, pewter, or the silver used in Europe at that time.

The most notable innovation in the Chinese porcelain industry in this period of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) was the new low-fire polychrome ceramic overglazes. Called “foreign colors” or “soft enamels” or “Famille rose,” this enamelware allowed a greater range of color and tone than was previously possible and enabled the depiction of more complex images, including flowers, figures and insects. The ceramics industry applied these new liquid pigments or overglazes on the vase in a separate firing after the first high firing of the porcelain or after a high-fire cobalt blue underglaze. The thick opaque white overglaze made with an arsenic base was mixed with different pigments for this vase in the four colors of clouds and in the white cranes. In this vase you can see the build up of the color giving each cloud and each crane a slight three-dimensionality.

In the twentieth century “made in China” implied a cheap imitation. But for hundreds of years, Chinese porcelains were highly prized and much sought after. The export porcelains were expensive works of art collected by the French King Louis XIV, and the Persian and the Ottoman royalty, who each had special rooms built to show off their collections of Chinese porcelains. The tastes of both the Europeans and the Chinese were influenced by the international trade of tea, silk, and porcelain, and created powerful merchant classes in China and Europe especially in the 17th & 18th centuries.

Porcelain was a craze in Europe but the secrets of how to reproduce the Chinese porcelain clay and their glazes remained a mystery. Learning the secrets of creating porcelain became an obsession of many, including the German king “Augustus the Strong” who locked up a German alchemist Johann Friedrich Böttger for five years supervised by mathematician/philosopher Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus. The king hoped that they would figure out how to turn dirt and clay into gold. After five years they cracked the porcelain code and started the first very famous European porcelain production in Meissen, Germany in 1710. At the same time, Jesuit monks sent to China printed letters home describing the Chinese ceramic secrets. This new technical knowledge in Europe and a complacent leadership in China laid the foundation for European ceramic production to eventually overtake the Chinese in the 19th century.

The South China region of Jingdezhen had been the center for ceramic production since 1000 CE because it has large deposits of the raw materials - high quality kaolin and china stone (petuntse described above) needed to make porcelain. Jingdezhen also has pine forests to fuel the kilns in order to bake the clay, and rivers connecting north to markets in Beijing, the political capital, and south to the export harbor in Canton. To give an idea of the historic scale of the Chinese ceramic industry, earlier, in 1433 during the Ming dynasty, a single order from the Chinese royal palace came for 443,500 pieces of porcelain, all with dragon and phoenix designs. The Jingdezhen Imperial Kilns included both the royal and private ceramic industry in China and employed hundreds if not thousands of workers organized into specialties to increase efficiency and consistency. These specialities included mining the raw materials, mixing the kaolin and china stone, fermenting the clay, forming the vessels, firing, painting the lines, painting the colors, second firing, packing and shipping. Each piece of porcelain passed through the hands of some seventy men with almost no marks from any individual hand.

Then during the chaos of the fall of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), rebels in South China destroyed the imperial porcelain kilns. The conquering foreign Qing emperors were Manchu people, primarily military tribesmen from Manchuria in the northeastern part of China, and they were culturally and physically different from the majority Han Chinese. To legitimize their rule and stabilize the economy and the social order, the Qing rulers needed to reestablish and maintain the ancient and respected traditions of the neo-Confucian Ming government bureaucracy as well as its scholarly literati and its international trade. Fortunately, the Manchu rulers of the Qing Dynasty (1644 - 1911) were enthusiastic patrons of the arts and respectful of the recently deposed Ming dynasty artistic traditions. The first Qing dynasty emperor Kangxi rebuilt the economically important imperial kilns in 1683 and the designs became more varied.

The third emperor Qianlong (1736-1796) personally appointed Tang Ying supervisor of the Jingdezhen Kilns because Tang Ying knew every specialty and painted some of the porcelains himself. Under his leadership Chinese porcelain flourished until his death in 1756. His factory reproduced ancient ceramics and developed new designs and he encouraged designs from scroll paintings on the porcelains. We know this vase was made at the peak of the porcelain art from the Jingdezhen marks on the bottom of the vase (which we cannot see). The marks tell us that “Vase with Flying Crane over Islands of Peach Trees” was made as a birthday gift for a wealthy Chinese merchant at the Jingdezhen kilns between 1736-1795.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Pattie Porter Firestone, February 2018

Bibiliography

Campbell, Gordon. “The Grove Encyclopedia of Decorative Arts”. 2 volumes: print and e-reference editions available. 2006

Eberhard, Wolfram. “A Dictionary of Chinese Symbols, Hidden Symbols in Chinese Life and Thought”. Translated from the German by GL Campbell. Routledge. London. New York.

Elliot, Mark C. “The Manchu Way, The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China”. 2001. Stanford University Press.

Fang, Lili. “Chinese Ceramics (Introductions to Chinese Culture)”. Mar 3, 2011

Fong, Wen C. & James C.Y, Watt. “Possessing the Past, Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei”. 1996. Harry N. Abrams, Inc, NY.

Krahl, Reginal. “Ceramics in China: Making Treasures from Earth”. Brussels.

Lee, Sherman. “CHINA, 5,000 Years, Innovation and Transformation in the Arts”. 1998. Guggenheim Museum.

Smith, Bradley & Wan-go Weng. “China, A History in Art”. Double Day

Sullivan, Michael, “The Arts of China”. 1996. University of California Press.

Tregear, Mary. “CHINESE ART”. Revised Edition. Thames and Hudson

Williams, CAS. “Chinese Symbolism and Art Motifs”. 1974. Charles E Tuttle Company. (Kelly & Walsh, Shanghai. 1941).

WEBSITES

https://www.britishmuseum.org/pdf/Chinese_symbols_1109.pdf

http://www.chinaonlinemuseum.com/ceramics-famille-rose.php

http://www.chinasage.info/symbols/nature.htm#XLXLSymCloud

http://www.learn.columbia.edu/nanxuntu/html/economy/

https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/now-at-the-met/2015/how-to-read-chinese-ceramics

http://www.nationsonline.org/oneworld/Chinese_Customs/clouds.htm

https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/the-european-obsession-with-porcelain

Https://www.primaltrek.com/impliedmeaning.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crane_in_Chinese_mythology

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lingzhi_mushroom

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jingdezhen_porcelain

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Peach_Blossom_Spring

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xian_(Taoism)

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Made for a birthday celebration, this round, bulbous-shaped vessel and surface decorations all denote good fortune and long life: cranes carrying the attributes of the Eight immortals, colorful clouds, deep ocean, and islands/mountains of fruit-bearing peach trees.

- Ridley-Tree Gallery, 2016