David Alfaro Siqueiros

Mexican, 1898-1974 (active USA)

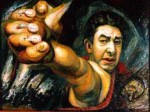

La esteta en el drama, 1944

Duco (pyroxilin) on board

47 5/8 x 35 7/8 in.

SBMA, Gift of Gordon and Suzanne Johnston

2000.63

David Alfaro Siqueiros, Self-Portrait, 1943, oil on canvas

"The artist must make up his mind to serve either the bourgeoisie or the proletariat. I believe that painting and sculpture should serve the proletariat in their revolutionary class struggle.” - Siqueiros

In the 2002 movie Frida, the character of Siqueiros states: "I'd rather have an intelligent enemy than a stupid friend."

RESEARCH PAPER

David Alfaro Siqueiros was a revolutionary in his art and in his life. In 1914, when he was eighteen and a student at the prestigious School of Fine Arts in Mexico City, he left the school to fight in the Mexican Revolution against the federal authorities. In 1937, after gaining world-wide fame as one of the three great muralists in Mexico, he joined the Republican Army in the Spanish Civil War fighting against the fascists. Siqueiros was always a political activist. He was jailed or exiled from his Mexican homeland numerous times for his political actions. In 1941, those activities resulted in his being jailed and then exiled to Chile.

In 1944, thanks to the intervention of important personal friends in Mexico, Siqueiros was allowed to return. At that time, he and his wife, Angelica, moved in with her mother in Mexico City. It was there that he painted a number of smaller works of art (as opposed to his usual mural paintings)—"La Esteta en el Drama" was one of them. Siqueiros gave the painting its title. It could be translated in numerous ways. Aesthete could refer to art or to its original Greek meaning of perception. Drama could mean what it means in English, or it could reflect its original Greek root meaning, action.

This painting, "La Esteta en el Drama", does not vary from his Marxist ideology. The woman portrayed is obviously in great anguish. She looks to be of indigenous Mexican stock. Whatever the reason for her pain, the viewer must feel for her. It is pure Siqueiros and his alignment with the poor and downtrodden.

The pose of the woman in the painting was thematic of several similar paintings he created around the same time. In those, the upper torso of a person is shown in a dynamic posture. The face is always dramatic. One or both hands are clinched into fists, knuckles prominent, and reflect the emotions shown on the face. The clinched fists, always in the forefront of the paintings, are as big or bigger than the face in the portrait. The colors are bold and bright. Red is used to highlight features in the paintings, especially on and around the hands.

Siqueiros seldom painted using the standard oil on canvas model. He once wrote, “I repudiate so-called easel painting and every kind of art favored by the ultra-intellectual circles because it is aristocratic and not of the working class.” In keeping with those principles, from his twenties and onward, he experimented and used new and different methods and materials to express himself. In keeping with his political views, he often preferred materials he purchased at a hardware store to those from an art store. When he lived briefly in Los Angeles in 1932, he was a guest at the house of a Hollywood director. At that time, he visited film studios and was inspired by the techniques and materials used by Hollywood set designers.

The surface he used to paint "La Esteta en el Drama" is wood composition board, or Masonite. The paint he used was Duco or pyroxylin, a paint lacquer created in the 1920s for use on automobiles because of its high-gloss finish. As an industrial paint, it was usually applied with a spray gun. Siqueiros once called the paintbrush an outdated product of the European bourgeoisie. It is likely that at least some parts of La "Esteta en el Drama" were painted with a spray gun—or a “mechanical brush,” as Siqueiros liked to call it. Today, the technique is usually called airbrushing. A standard paint brush may have been used in the painting where a brush stroke effect desired. A palette knife was also likely utilized.

The anguish of the woman in "La Esteta en el Drama" is made grotesque by the balled, gnarled fists and the exaggeration of the bone structure in the hands and wrist under the stretched skin. The knuckles are very prominent. Right next to the left wrist on the cuff is a tiny, blurred image of a figure painting at an easel, an obvious reference to the disdain he had for traditional European painting styles.

Of the Los Tres Grandes, the three great ones, of 20th-century Mexican muralists: Diego Rivera, Jose Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros, Siqueiros held many distinctions. He was the youngest and lived to be the oldest; he was the most passionate about his political beliefs; and he was the most innovative in his creative use of modern technology. He gave experimental art workshops in New York City in the 1930s that influenced many young American artists who participated, including Jackson Pollock. The workshop’s purpose was to do experimental, large-scale work using industrial tools and materials. Specifically, no oil paint or canvas were to be used. Automotive enamels and lacquers on wood panels were their medium. It was during this workshop that Siqueiros and his students played with the drip technique. They called it “controlled accidents and dynamism.” Jackson Pollock’s first drip paintings and many of his artistic techniques using different mediums originated in those workshops.

Siqueiros’s influence in both modern North American art is profound. Of the Tres Grandes, he is undoubtedly the most modern, and the one most likely to be emulated by other artists in the future.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Manuel Rangel, 2023

BIBLIOGRAPHY

David Alfaro Siqueiros, art and revolution. Translated by Calles, Sylvia. London: Lawrence & Wishart. 1975.

David Alfaro Siqueiros Biography. The Biography.com website. https://www.biography.com/artists/david-alfaro-siqueiros. April 14, 2021.

Lucie-Smith, Edward (2004). Latin American Art of the 20th Century (2nd ed.). New York: Thames & Hudson.

Stein, Philip (1994). Siqueiros: His Life and Works. New York: International Publishers. ISBN 0-7178-0709-6.

David Alfaro Siqueiros, art and revolution. Translated by Calles, Sylvia. London: Lawrence & Wishart. 1975.

The New York Times. “Siqueiros, Muralist and Exponent of New World Proletarian Art, Dies at 77.” January 7, 1974.

COMMENTS

Brief Biography of David Alfaro Siqueiros

David Alfaro Siqueiros long affirmed that he was born in Santa Rosalia (today Camargo), in the state of Chihuahua, in 1896. However, recent investigations call this date into question; Siqueiros' passports, for example, give birth dates of 1895, 1896, and 1899. In 1913, after studying in religious schools in Mexico City, he enrolled in the Open Air School of Santa Anita, an institution affiliated with Mexico's official art academy. In 1914 and 1915, during the Mexican Revolution, he served as secretary to General Manuel Dieguez and fought in several battles. In 1917, he enrolled in the National School of Fine Arts, also in Mexico City. There, in the following year, he exhibited his work for the first time. In 1919, Siqueiros was sent to Europe as a military attaché, and lived there until 1922.

From 1922 to 1924, Siqueiros worked as a muralist in the National Preparatory School, and founded El Machete, the official publication of the Syndicate of Painters, Sculptors, and Technical Workers, to which he contributed politically-inspired woodcuts. In 1924, when his contracts were canceled, Siqueiros moved to Guadalajara, where he worked on a second mural program and eventually abandoned painting altogether to dedicate himself to union organization in the state of Jalisco. His communist stance and intensive militancy led to his imprisonment in Mexico City's penitentiary in 1930.

In November 1930, Siqueiros was released from prison under the condition that he remain under house arrest in the town of Taxco, Guerrero. In January 1932, his first solo exhibition was held in Mexico City, and soon thereafter, he and his companion, the Uruguayan poet Blanca Luz Brum, left for Los Angeles. In 1932, Siqueiros painted three murals in Los Angeles, and exhibited his work at the Stendahl Galleries in that city. When his visa was not renewed, he and Brum left for South America, where he worked, lectured, and painted a mural in a private residence in Buenos Aires, entitled Plastic Exercise (1933). In New York briefly in 1934, Siqueiros spent 1935 in Mexico City, and returned to New York in 1936, where he founded the Siqueiros Experimental Workshop, a collective space closely affiliated with the Communist Party. In 1937 and 1938 he again abandoned painting, serving in the Republican Army during the Spanish Civil War. In 1939, back in Mexico, Siqueiros continued to work as a political activist, but also created an important series of paintings, most of which were exhibited in the Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York City in January of 1940. Working with a team of artists on his first major mural in Mexico City, he produced Portrait of the Bourgeoisie for the headquarters of the Mexican Electricians' Union.

On the night of May 23, 1940, Siqueiros led an unsuccessful attack on the home of Leon Trotsky, then living in exile in Mexico City. Siqueiros was sought by the police and eventually caught and arrested in August, after Trotsky's assassination by a second team. Following his release in April 1941, Siqueiros left for Chile. In 1943, with assurances that he would not be prosecuted, he returned to his native Mexico where spent the remainder of his life solidifying his position as one of the three great muralists in the country. He died in 1974.

http://www.sbma.net/siqueiros/bio.html

Prepared for the SBMA Docent Council website by Ralph Wilson and Loree Gold 2013

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

In The Aesthete in Drama, Siqueiros manipulates color, form, volume, and texture to express human suffering. Equally as modern as his technique are the dramatic close-up views that Siqueiros adapted from avant-garde film and photography. While addressing political concerns ranging from revolutionary turmoil to the conditions of the working class, the painting is also an ironic statement about the role of the artist in society.

At first glance, the title of the work suggests that the robed woman with her emotive expression and gesture is the aesthete in drama. However, the diminutive figure depicted on the edge of the woman’s sleeve can also be read as this title character. Identified by his easel and by the landscape he is painting, the artist is oblivious to the drama unfolding around him.

The 1922 manifesto, A Declaration of Social, Political and Aesthetic Principles, which Siqueiros co-authored with fellow muralists Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco and others, boldly states, “We repudiate so-called easel painting and every kind of art favored by the ultra-intellectual circles, because it is aristocratic and we praise monumental art in all its forms, because it is public property.” However, by the1930s Siqueiros and his compatriots incorporated easel painting into their repertoire to support themselves financially.

- SBMA title card, 2013

David Alfaro Siqueiros called for the creation of a political and revolutionary art, but he also encouraged artists to consider the application of aesthetic values to the making of this are. He spoke of the artist’s ability to elicit psychological reactions through the manipulation of colors, tones, values, forms, volumes, spaces, and textures. Further, he believed that new art forms demanded new media, and he experimented with industrial paints, such as Duco (pyroxilin) in order to achieve even greater expressive effects. Equally as modern as his technique are Siqueiros’s dramatic close-in and blown-up views drawn from avant-garde film and photography.

In his work Siqueiros employs all of the artistic recommendations as means to express human suffering. While addressing political concerns from revolutionary turmoil to the conditions of the working class, the painting is also an ironic statement about the role of the artist in society. The diminutive figure depicted on the woman’s sleeve is the “aesthete” referred to in the painting’s title. Identified by his easel and by the artwork he is creating, the “aesthete” is oblivious to the drama taking place around him. This work references Siqueiros’s view that the role of the artist is to bring about social change, most effectively activated through political public art, not personal easel painting.

- SBMA Wall Text, 2000