Techniques Paper

Roman Marble

There were two distinctly different influences that shaped the development of Roman sculpture. The earliest was that of their immediate neighbors to the north, the Etruscans, whose culture was flourishing when Rome was founded. By the late sixth century BCE, Etruscan funerary art had reached its zenith. Tombs were decorated with wall paintings and the sarcophagi were adorned with life size terracotta figures that resembled the deceased. The poses and features were animated and lifelike, quite unlike the stiff stone sculpture of the contemporaneous Archaic age in Greece.

Roman portraiture and historical art is descended from this legacy. Likenesses of distinguished ancestors – often wax death masks – were created for display at funerals and other public occasions. There was thus a three dimensional model of the head of the deceased that could survive for several decades – a model that could be used for faithful reproduction in a subsequent marble sculpture. The notion of verism, the accurate representation of the immediate visual and tactile appearance of the subject, warts and all, became the norm of Roman portraiture.

The second influence began in 146 BCE when Rome sacked Corinth and made all of Greece a Roman province. The Romans developed a taste for Greek sculpture from admiring the hundreds of Classical and Hellenistic statues brought home as booty by their victorious armies. Roman ideal sculpture was born – that which depicted deities, mythological characters, personifications or allegorical figures, figures from another world, not our own. Perfect proportions and idealized beauty were the two norms inherited from the Greeks. These works were commonly produced in multiples known as replica series: a set composed of works that may have differed in material, size, quality and iconographic minutiae, but that were visibly related to a common prototype.

The Roman sculptors were skilled artisans and were capable of producing works in both the portrait/historical and ideal styles, whichever their patron desired. The materials, tools and methods were the same. In both cases they essentially made replicas of the original work, be it a wax mask, a looted sculpture, or a derivative product. There was considerable breadth in how accurate the copy was, varying from an exacting depiction of a well known public figure to free variations derived from Greek originals. Roman replicas were works of judgment and skill. Many were signed conspicuously with the maker’s name, not the name of either the work or the original artist. The pride of the carver was shared by the purchaser, who displayed the signed work for visitors to admire. (I found no mention in the literature regarding original works from the imagination or using sitters, nor any reason to rule this out.)

Of all the materials that the Roman sculptors had to choose from, marble was the hardest and most time consuming to carve. It had the advantage, however, of not being foliated (particles aligned in parallel rows) so it could be worked in any direction. Marble is a metamorphic rock formed when limestone is exposed to the heat and pressure of geologic activity. It is composed primarily of calcite and contains additional minerals such as clay minerals, micas, quartz, pyrite, iron oxides, and graphite. It is the particular mix of these trace minerals that produces the unique patterning of different varieties of marble.

The unique pattern of each variety of marble is determined by where it was quarried. Parian marble (Lansdowne Hermes) came from the island of Paros. Pentelic marble (Athena, Three Dancing Nymphs, Funerary Loutrophoros) came from Mount Pentelicus in Attica. Pentelic marble weathers to a slightly golden color. Carrara (then known as Luna) marble, quarried on the northwest coast of Italy, is a white, fine-grained marble with a blue-gray tinge preferred by sculptors from Roman times to the present day. Many marbles in Ludington Court were sculpted from Luna or a similar stone.

The Romans were masters of geometry and measurement. Their toolkits included calipers, compasses and rulers. Apprentices would generally sculpt the bodies in advance. Copies of the same type of body were used for gods, heroes, and portrait statues of mortals. When a commission came in, the master would sculpt the head and it would be attached to the preexisting body with iron dowels and powerful adhesives. The principle measurements needed to establish the proper proportions of the head were:

1. Chin to top of head

2. Depth from nose tip (or brow) to back of head

3. Width across ears (or hair if ears were hidden)

4. Width across cheek bones

5. From chin to eyebrows (or chin to nose and nose to eyebrows)

6. From wing of nose to orifice of ear

When rendered accurately, these proportions would establish the character of the subject to a greater degree than would the surface features. In addition to freehand methods, the pointing method was also used. A grid of string squares would be set up on a wooden frame that surrounded the original and a similar frame would be set up around the block from which the copy was to be carved. Measurements could then be made to the original from each point on the grid and duplicated in the copy.

The principle tools in the Roman sculptor’s workshop were made of low-carbon steel forged from iron (similar to their modern counterparts illustrated below). They included points, claw tools, small gouges, flat and bull-nosed chisels, and strap drills. Iron-headed hammers and wooden mallets ranged from 4 1/2 pounds, used for roughing-out, to 1 1/4 pounds for finish work. Marble blocks over 4 feet tall were heavy enough to be carved freestanding, but smaller blocks such as busts had to be fixed into a wooden frame for stability.

The marble block was first roughed-out using the point. A circle of 6 or so direct blows about an inch apart would fractured off small flakes of marble about 1/8 inch thick. About 75 percent of the marble in the block would be removed, to about 1/4 inch above where the finished surface would be.

The general features were then carved with claw tools, aka tooth chisels, which left a grooved surface resembling a Ruffles potato chip. This would take the surface down to about 1/8 inch above the finishing point. (Some sources suggest that claw tools were not used until the Renaissance. Others suggest they were known to the Romans as well.)

The gouges were used to remove the ridges left by the claw tools and shape the details. These were handled in long parallel strokes, clarifying the forms and bringing them down to 1/16 inch of the finished surface.

.

The chisels were used for detail work, to smooth the finished surface, and to complete the carving. They could be driven by a hammer or a wooden dowel held against the surface to act as a fulcrum.

.

The drills had solid blade-shaped bits or larger tubular bits and were operated with a bow by the sculptor himself or with a longer thong drawn back and forth by an assistant. They could be used to pierce large gaps or produce deep channels, first as a series of single holes placed close together, then worked into a continuous line with chisels. They could also be braced at an angle to produce short carving channels rather than single holes. The drills were indispensable in rendering hair and beards.

.

.

Finally, the surfaces were prepared with rasps then painted with pigments suspended in beeswax that was probably liquified with soda. Bright combinations of red, pink, black, brown, blue, yellow, green, gold, or white were utilized for the clothing, hair, and details of the eyes, eyelashes, mouth, nostrils, and other attributes. Many sources of pigment are identified in Vitruvius’ manual De Architectura. Black was drawn from the carbon created by burning brushwood or pine chips. Ocher was extracted from mines and served for yellow. Red was derived either from cinnabar, red ocher, or from heating white lead. Blue was made from mixing sand and copper, and then baking the mixture. The deepest shade of purple was usually obtained from sea whelks. The pigments could not be mixed because the molecular densities varied and the colors would separate as they dried. Some sculptures were completely painted and gilded, effectively obscuring the marble surface; others had more limited, selective polychromy used to emphasize details. Areas of human flesh were often left unpainted. In the 1st century CE, unpainted skin surfaces were smoothed using emery or pumice. By the 2nd century they were often given a high polish (method unknown). In the 2nd and 3rd centuries it also became customary to incise the irises and pupils to enhance the intended gaze and preserve it in case of repainting.

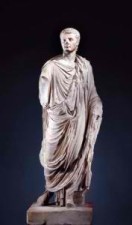

Unknown Roman

Caligula, 1st c. CE

Marble

80 x 26.5 x 19.5″

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

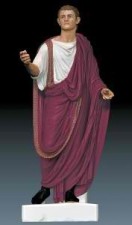

This digital model shows how ancient Roman artists likely would have styled the sculpture.

Reconstruction by Matthew Brennan, Virtual World Heritage Laboratory

.

.

.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Mike Ramey, October, 2013.

Bibliography

Abbe, Mark B. “Polychromy of Roman Marble Sculpture”. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–.

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/prms/hd_prms.htm (April 2007)

Adamian, Elmira. “Handling Session: Fresco Painting”. Education Department, Getty Villa. December 8, 2013.

Bieber, Margarete. Ancient Copies: Contributions to the History of Greek and Roman Art. New York: New York University Press, 1977.

Brinkmann, Vinzenz. Circumlitio: The Polychromy of Antique and Medieval Sculpture. London: Hirmer Publishers, 2010.

Del Chiaro, Mario A. Classical Art: Sculpture. Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1984.

Department of Greek and Roman Art. “Roman Painting”. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–.

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ropt/hd_ropt.htm (October 2004)

Janson, H. W. History of Art, Fourth Ed. New York: Abrams, 1991, 229-243.

Kleiner, Diana E.E. Roman Sculpture. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1992.

Marvin, Miranda. “Roman Sculptural Reproductions or Polykleitos: The Sequel”. In Anthony Hughes and Erich Ranfft. Sculpture and its Reproductions. London: Reaktion Books, 1997, 7-28.

Miller, Alec. Stone & Marble Carving. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1948.

Turner, Jane, Ed. “Rome, Ancient, Sculpture”. In The Dictionary of Art (Grove). London: Macmillan, 1996, v. 27, 8-47.