Rufino Tamayo

Mexican, 1899-1991 (active USA, France)

Noche y día (Night and Day), 1953

oil on canvas

32 x 39 1/2 in.

SBMA, Gift of Glen Larson

1998.76

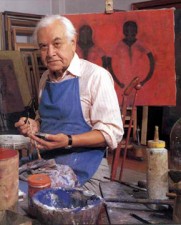

Self portrait from 1931

"…as we use an ever smaller number of colors the wealth of possibilities grows. Pictorially speaking, it is more valuable to exhaust the possibilities of a single color than to use a limitless variety of pigments." - Rufino Tamayo

RESEARCH PAPER

The Artist

Rufino Tamayo was born in Oaxaca, Mexico in 1899 His family was of Zapotec Indian (the people of the clouds) origin. The artist’s formal art education began in Mexico City at the San Carlos Academy.

In 1921, Rufino served as Chief of the Department of Ethnology, drawing in the National Museum of Archeology in Mexico City. It was here that he developed his reverence for pre-Columbian art which would turn out to be a confirmation of his heritage rather than a discovery and, as we shall see later, a confirmation that would play a large part in the iconography of his works.

1926 was another turning point for Tamayo as he had his first exhibition and his first trip to New York. The years following this were filled with international exhibitions and acclaim, study of the movements that were taking place in Europe and murals for, among other locales, the Conservatory in Mexico City, the art library at Smith College in Massachusetts, the Historical Museum in Mexico City and a mural for UNESCO in Paris. It is particularly interesting to note that in doing these and many other murals, Tamayo resisted the movement having to do with Mexican revolutionary and nationalistic art and chose not to be a part of it.

When asked to do a mural in the Palace of Fine Arts in Mexico City, Tamayo agreed and rendered the theme of his nation’s birth but he much preferred larger and more universal themes. While Siqueiros, Rivera and Orozco tried to enlist him into their nationalistic approach to art but Tamayo had the whole world in mind not the Mexican revolution so fresh in everyone’s memory. In fact, he lived in Mexico City until 1936 and then lived for 18 years in New York, followed by 10 years in Paris and environs. In 1964, Tamayo returned to Mexico to live out his life. He was truly cosmopolitan and international, honored in Tokyo, Florence, Paris, New York, Mexico, Canada, Israel, Venezuela and Russia among others.

The fifties brought with them space information and investigation that was not lost on Tamayo. It was during this time that he painted a number of canvases having to do with the heavens, a famous example was entitled Woman Reaching for the Moon (1946). I ordered a copy of Women Reaching for the Moon, but instead got Dancers Over the Sea from 1945. While Dancers does not have the celestial qualities of Women Reaching for the Moon, it nonetheless gives us a weightless look at dancers who seem to be self-levitating into a pink sky. By this time Tamayo had discovered the power of color and form, having been greatly influenced by an exhibition in 1940 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York that showcased Klee, Braque, Matisse and Picasso.

An exhibit in New York of Tamayo’s paintings of 1980-1990 show his fear and consternation over the plight of mankind and some feel that this was Tamayo’s ultimate goal, that is, to speak for universal consciousness through a medium he had made all in own on so many levels.

I believe there is a striking comparison between two early paintings, the Boy in Blue of 1928 and the Tortilla Maker of 1931 and the The Boy with the Bass Viol(?) of 1990, one of the last paintings completed by Tamayo. The latter is strikingly realistic and representational, this, after years of geometry and using spatial license. It almost seems to me that Tamayo was making a turn here, using his color prowess developed through the years and yet abandoning the simplification process. The truth is that we will never know the answer or if this was truly a change because Tamayo died six months later in mid 1991.

THE ART

Noche y Dia is a celebration of all of the elements that Tamayo utilized so efficiently, namely color, duality, pre-Columbian art and the popular arts of Mexico.

COLOR

The colors used in this painting are perhaps not the gay colors that one might expect, indeed, they are of the earth and as Tamayo has stated in his theory about Mexican color, "People believe that Mexican pictures should be very gay. On the contrary, my country is tragic because of a long history of foreign domination since the Spaniards………Mexico is poor, the colors used are cheap. Blue, used to whiten clothing, earth colors to paint houses because they are cheap etc.". Tamayo believed that the bright colors: scarlets, purples and yellows and other brilliant hues also played a role because the country was tropical and Fiesta colors were gay but the "poor" colors were his idea of Mexico.

In Noche y Dia, Tamayo has divided the canvas into four segments. The upper left is the brightest and contains the sun as would be expected and diagrams of daytime constellations, the lower left is earth-brown divided again by constellation diagrams and containing a section of clear blue water, the upper right is a dark night sky containing the constellations which now have the luminescent stars and a bifurcated moon with both dark and light sides and two large comet like celestial objects, and the lower right the darkest segment of all four also has the constellations (stars), darkest of blue water and a dark brown/black earth. When one looks at this work it is apparent that the physical art and application of color rather than any meaning is the prominent point here. Tamayo made clear over and over again that he was only trying to express the essence of things, to simplify and to restrict and that subject matter was not his primary concern and that it should be sublimated to painting design, space, form and color. Tamayo has achieved a monumentality in his works due not to dimensions but because they are austere and uncluttered with an unmistakable strength.

Gray is the comfortable shade of Tamayo’s palette. He has said, "Whiteness of canvas bothers me. The first thing that I usually do when I begin a painting is to lay down a coat of grey, but when white is called for as in Two Figures in White (1988), the white is actually a mix of grays, blues and pinks."

DUALITY is the essential principle of the pre-Cortesian world as regards Gods, nature, lore and art. For example: sowing and harvest, birth and death and Noche y Dia etc.

In this painting, duality is everywhere; light and dark, earth and sky, liquid and solid, a moon divided into dark and light sides, constellations that are dark and geometric by day starry and luminescent by night.

Tamayo frequently included time references and clocks in many of his paintings and while Noche y Dia does not have a clock, per se, it has other pulses of ancient America, as the pre-Columbians knew it, time charted by the omnipresent moon and stars and most of all, the sun. This painting is divided into quadrants. The upper quadrants signify the heavens and the lower quadrants signify the earth but again there is duality and this time between ancient and modern because the curve of the earth’s surface is ever so slightly recognizable, a phenomenon not adopted until after Columbus.

PRE- COLUMBIAN art had an enormous impact on Tamayo. One of his first jobs was as Chief of the Department of Ethnology for the National Museum of Archeology in Mexico City. In his position, he drew many pre-Columbian artifacts and developed a lifelong affinity for this art form. In the fifties and sixties, Tamayo explored the heavens and the metaphysical beliefs inherent in ancient Mexican art, namely the gods of the heavens and the cosmic movements associated with time. Perhaps significantly, this period also involved the beginnings of modern space exploration. Though Noche y Dia does not explicitly depict these Gods and associated creatures, it does give us a good look at their homes; the heavens themselves and the constellations contained therein. This painting was done in l953 but it looks as though it would have been comfortable having its genesis in 1500 B.C. The Nobel Prize winner, Octavio Paz has said that Tamayo’s attitude in all things is ancient and very near the source.

THE POPULAR ARTS OF MEXICO contain no aesthetic revolutions and really encourage no creative changes. It’s origins were probably the magic that is part of all religions and beliefs, the talismans, the relic, the figurines. In 1979, the Guggenheim Museum assembled a show of Tamayo’s works, coupled with the popular arts of Mexico and pre-Columbian artifacts. The show was a wild success and demonstrated the palpable relationship between these art forms in Tamayo’s works.

In Noche y Dia, the magic that unites all beliefs runs as a current throughout every segment.

CONCLUSION

Tamayo’s art is elemental and yet complex, it is monumental regardless of size due to the essence of the colors he uses and generally the spare forms utilized. An example of both is Square Head done in 1978. The head has been reduced to a square, a rectangle, two small circles and a body being held to the head with the thinnest of lines. The square head is backed by a blue square, giving depth to the work and contrasting to the rest of the background. A "typical" Tamayo is easily brought to mind’s eye because of its voluptuous theme, form and color.

Rufino Tamayo’s art has something for all of us as it is about us and for us and expresses universal themes. Who in this world has not admired a daytime sky, the color of water or the changes apparent in the heavens after dark? It is a distillation of what we see about us, not unlike the art of the pre-Columbian who had no other direction but that which was presented daily to him in his corner of the universe. In researching this piece, it has occurred to me that one could present Noche y Dia to a tribe in the jungles of Borneo, to a group in a Parisian art gallery and to a fourth grade class from Santa Barbara (as I have done) and without exception, they would all be able to divine what the artist has given us in this painting. Truly, an example of the universality, that Tamayo consciously sought throughout his career.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

NOCHE Y DIALewin, B. Galleries. Rufino Tamayo.: B. Lewin Galleries Publisher,

Beverly Hills, California. (No date).

Marlborough Gallery, Inc., Rufino Tamayo. September 26 – October 16, 1990.

Partridge, T., Maillard,L., and Peacock, M., eds. Dictionary of Modern Painting.

Oxford University Press, New York, 1954.

Paz, Octavio and Lassaigne, Jacques. Rufino Tamayo. Barcelona, Spain:

La Poligrafa, South America. 1995.

Phoenix Art Museum and Friends of Mexican Art, Tamayo, Phoenix, Arizona,

March 1968.

The Soloman R. Guggenheim Museum Foundation, Rufino Tamayo: Myth and

Magic, New York, New York, 1979.

Prepared for the SBMA Docent Council by Nancy Estes, 1999

Rufino Tamayo in his San Angel District studio in Mexico City.

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Rufino Tamayo is recognized for the manner in which he blended the lessons of international modernism with his personal interpretations of Mexico’s folk traditions and pre- Columbian history. Noche y día belongs to the artist’s “Constelaciónes” (Constellations) series begun in 1946, in which the celestial sphere becomes a means to investigate natural and metaphysical concerns. For the artist, the cosmos represented a vast, formidable field of the unknown—extending from ancient Maya sky watchers to modern space exploration. In 1960, the artist declared, “All the old molds of art and science have been broken. A new era has been opened with interplanetary space travel. And if everyone is now looking for a new language, the painter cannot remain behind.”

- SBMA title card, 2013

Rufino Tamayo’s importance in the history of twentieth-century art is based on his exploration of the poetic and formal possibilities of painting. Widely recognized as one of Mexico’s major modern artists, he is highly regarded for the distinctive manner in which he interwove the lessons of international modernism with his personal, apolitical interpretations of Mexico’s past, particularly its folk traditions and pre-Columbian history.

Noche y día reflects Tamayo’s fascination with the heavens, which was stimulated, in part, by his appreciation of pre-Columbian cosmology. During the 1950s and 1960s, in a sequence of interesting variations on Joan Miró’s Constellations of the late 1940s, he used the theme of constellations to explore the natural and metaphysical concerns prompted by these cosmological beliefs. Tamayo developed these ideas in an extended series of works that also addresses the issue of modernity and its implications as suggested by the new era of space exploration. Symbolizing the cosmic cycle of day and night, Noche y día belongs to this series of abstracted celestial landscapes.

- SBMA Wall Text, 2000