Rufino Tamayo

Mexican, 1899-1991

Monumento al héroe desconocido (Monument to the Unknown Hero), 1989

steel with epoxy resin and crushed marble

80 x 23 ¾ x 19 ¾ in.

SBMA, Gift of Marshall and Helen Hatch

1997.21

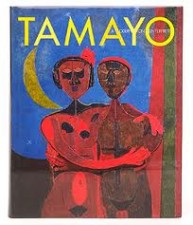

Undated photo of Tamayo, and above right, a mixed media print, Torso in Pink, 1980, with similar motif (not in SBMA collection).

COMMENTS

Tamayo’s Abstract Figuration

By 1940, Tamayo had established the definitive form of abstract figuration that made him one of the most celebrated painters of the twentieth century. After having experimented with a variety of artistic genres in his early work, he now focused on the human image as his principal preoccupation.

Tamayo’s figure painting of the 1940s and 1950s confirms the artist’s commitment to interpreting the human experience, while remaining dedicated to the modernist ethos of formal experimentation. He addressed a full range of emotion; love and hate, joy and despair, aggression and reconciliation, contentment and fear all found pictorial expression in his mature work.

Tamayo’s signature paintings exemplify the fusion of modernism he developed by freely combining modernist concepts and practices from Mexico, Europe, and the United States. Tamayo reinvented lessons of the School of Paris by adapting a Fauvist use of color and a Cubist treatment of form. He applied paint in broad areas of related tones that were non-descriptive, and he sectioned the human body and shallow spaces into geometric shapes and diaphanous transparencies that challenged traditional composition and perspective.

Tamayo was equally inspired by native sources. He intentionally drew from ancient and contemporary Mexican culture, the celebration of which was central in shaping modern national identity. In corollary, Tamayo also focused on the issue of ethnicity. By skillfully combining the indigenous and the European, a practice that had long defined art in colonial Mexico, he fashioned a new model for modern Mexican painting.

Tamayo further developed his fusion modernism by intersecting with the Abstract Expressionists who rose to prominence in New York following World War II. Tamayo exhibited with and was written about in the orbit of Abstract Expressionism because he so aptly represented the period interest in defining a specifically American modern art to counter the then-established European avant-garde.

Tamayo’s Universal Humanism

By 1968 Tamayo had developed fully the style that would mark his late-period abstract figuration. He left behind his searing and searching pictures of the 1940s and 1950s to practice, for the most part, a sentimental humanism, reinforcing a romantic definition of the human condition. Dramatically simplified figures with little or no features began to typify his painting. An aesthetic of similarity took hold, carrying with it the illusory message that the human condition was the same the world over.

Tamayo reinforced this lack of specificity by the materiality of his painting, for which his work is legendary. Rich, textured surfaces, with plenty of visual incidence and manipulation of color, went hand in hand with his genericized subjects. Even if there is a token reference to Mexico, it is superficially symbolic, because now the focus is on the value of sameness, while local differentiation is obscured. Tamayo’s late paintings thus shift from a conception of art as part regional, part international, to a universalized art.

Besides their message of universal humanism and their tour-de-force ability to show how late modern painting is still capable of arresting the eye, some of Tamayo’s great works of the 1970s and 1980s deal with a reality that cannot be sentimentalized: death. These pictures do not treat its actuality but rather the process of reflecting on a life lived and anticipating what is to come.

Adapted from the overview panels’ text for Santa Barbara Museum of Art exhibition Tamayo: A Modern Icon Reinterpreted (February 17 - May 28, 2007)

Born in 1899, Rufino Tamayo's brilliant career spanned seven decades. The celebrated Mexican painter, along with his notable contemporaries, Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros, embodied the spirit of his country's 2Oth-century art and was the focus of international attention. A native of Oaxaca in Southern Mexico, Rufino Tamayo was born to descendants of Zapotec Indians on August 26, 1899. Orphaned at the age of 12, he was raised by an aunt who owned a wholesale fruit business in Mexico City. His signature vivid palette may in part be based on the tropical fruits and images of his youth.

In 1917, he entered the San Carlos Academy of Fine Arts, yet soon left this institution in favor of independent study. Four years later, Tamayo was appointed the head designer of the department of ethnographic drawings at the National Museum of Archaeology in Mexico City. Here he was surrounded by pre-Colombian objects, an aesthetic force that would playa pivotal role in his life.

Recognition and celebrity came swiftly. The first exhibitions of Tamayo's artwork were held in 1926 in Mexico City and New York, where a one-man show was held at the Weyhe Gallery.

Rufino Tamayo married Olga Flores Rivas, an accomplished concert pianist, in 1934. At the same time, he began to exhibit his work internationally. Expanding his horizons, he spent long stretches in Paris and New York. Tamayo was exposed to the work of major European artists for the first time. From 1933 to 1980, Tamayo painted 21 murals for an array of universities, libraries, museums, civic and corporate clients, hotels, and an ocean liner. He was also an influential printmaker, and, in the latter part of his life embarked on the creation of sculpture.

Tamayo eschewed the highly politicized themes explored within the works of his peers, the three other Mexican titans, Rivera, Orozco and Siqueiros. He favored lyrical imagery and incorporated elements of Cubism, Surrealism, and Expressionism. Mexican folklore and his Indian origins provided a constant source of inspiration for Tamayo, producer of some of the finest murals and paintings in modern Mexico. Critics have extolled the artist's bold and saturated use of color as his most significant contribution to Modern art.

The Palace of Fine Arts, Mexico City, celebrated Tamayo's twenty-fifth year as a painter with a retrospective exhibition in 1948 (and a fiftieth anniversary show in 1968). Two years later, in 1950, three rooms at the Venice Biennale were devoted to his works. Tamayo won the Grand Prix for painting at the Sao Paulo Biennale in Brazil in 1953. He was made a Chevalier of the Legion d'Honneur by the French Government in 1957 ( elevated to officiel in 1970 and a Knight Commander of the Order of Merit in 1974), and was elected an honorary member of the American Academy and National Institute of Arts and Letters in 1961.

Some of the world's most prestigious museums, including the Guggenheim Museum and the Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo honored him with one-man shows. The largest Tamayo exhibition ever held was mounted in 1987; the Palace of Fine Arts and the Tamayo Museum in Mexico City brought together more than 700 paintings. Rufino and Olga Tamayo donated the Museum of Pre-Hispanic Mexican Art to their native State of Oaxaca in 1974. Their personal holdings of more than 1,000 pieces of ceramics and sculpture formed the cornerstone of the collection.

The Rufino Tamayo Museum of International Contemporary Art opened in Mexico in 1981. It displays many of the artist's works, as well as paintings, sculpture and drawings from his private collection, by luminaries such as Picasso, Miro, Leger and Dali. At the time, it was the first major museum not run by the Government.

Rufino Tamayo died in 1991 at the age of 92 in Mexico City

Copyright 2005 by the Artistic Gallery (http://www.artisticgallery.com/biographies/tamayobio.htm); edited by Ralph Wilson for the Docent Council, January 2013

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Beginning in 1989, during the last two years of the artist’s life, Tamayo began producing steel sculptures with a hand-applied patina, bestowing a sense of age and wear. As in some of his paintings, Tamayo used crushed marble to create a rich surface texture. These colossal sculptures reveal the artist’s longstanding interest in pre-Columbian art and culture, in particular stone sculpture. In 1922, Tamayo was appointed director of the Department of Ethnographic Drawing of the National Museum of Archeology, History, and Ethnography, tasked with examining and reproducing thousands of pre-Columbian objects as drawings for others to study.

Monument to the Unknown Hero mimics the form of a funerary bust atop a pedestal composed of geometric shapes, highlighting the interplay between positive and negative space. The “unknown hero” of this monument offers a universal alternative to the specific political and mythological figures represented by artists during and immediately following the Mexican Revolution.

- SBMA title card, 2013