Ena Swansea

American, 1966-

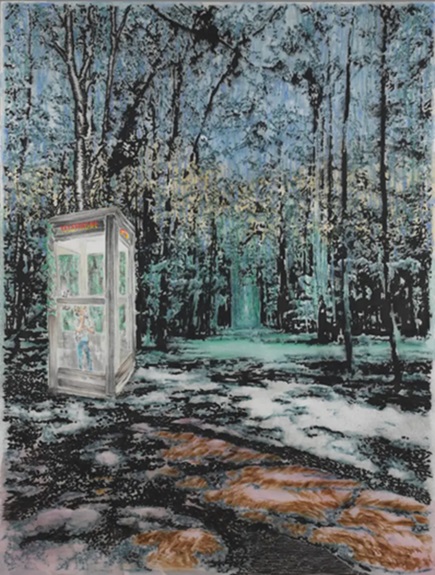

area code, 2019

oil and acrylic on linen

SBMA, Museum purchase with funds provided by Kandy Budgor; Luria/Budgor Family Foundation

2023.49

Portrait of the artist by Phong Bui, 2008, pencil on paper

"the ground is important in that every painting is backlit by it, and it is reflecting the light back out. oliver koerner von gustorf wrote that my ground reminded him of a television screen that is switched off. i like for the paint to change with the light, and be transparent, almost like a skin or glass on the ground.” - ena swansea

COMMENTS

Robilant+Voena is pleased to present Ena Swansea: New Paintings, the first exhibition at the gallery of American painter Ena Swansea, on view from 28 December 2019. The exhibition premieres a series of new paintings that blur the distinction between abstraction and figuration.

Using the artist's own photographs of the world around her as source material, the large-scale city scenes, rural studies and seascapes she paints have the evasiveness of dreams and intangible recollections. Ena Swansea creates spaces that are simultaneously ethereal in their shifting forms while remaining grounded in the atmosphere and symbols of the city.

https://www.robilantvoena.com/exhibitions/ena-swansea-new-paintings

Ben Brown Fine Arts presents “green light”, our third solo exhibition of American artist Ena Swansea, at the London gallery.

The gallery's first solo exhibition since lockdown, the title “green light” implies the chance to at last put one's foot on the gas, after being stopped and daydreaming outside of clock time, not knowing what day it is. Swansea's new series is representative of her decontextualised and timeless style, directing attention back to painting itself.

“green light” features recent large-scale canvases exploring motifs that recur within Swansea's practice, including snow, sea and the urban landscape, all bordering on abstraction and demonstrating the artist's ingenuity with the painted surface.

The brilliant and the muted colors of cinema, the velvet blacks, have stayed with Swansea's work since film school. These complex, layered paintings often collapse the subtle greys found in film into a dense and impenetrable dark field. Suspended in a plane of radiant color, the tension between light and darkness is simultaneously attracting and repelling. Swansea's attention to the effects of transparency can be seen in her experimental investigations into the myriad ways in which an image itself can be migratory, invoking an oblique political critique.

https://www.artrabbit.com/events/ena-swansea-green-light

There’s an aura of mystery to Ena Swansea’s big, impressive paintings at Ben Brown Fine Arts (‘green light’ to 30 July), and I wanted to know more. Just how are they made, and why do they show what they do? So I arranged a Zoom with the artist in her New York studio…

How does your use of graphite in paintings operate?

I discovered that graphite had this curious quality that it both sucks the light out of the image and also reflects and so brings light back into the image as you move around it. I’ve made many paintings on graphite grounds, but they only really thrive in perfect lighting – they can die otherwise. So I evolved into using what you might call graphite and its cousins… there’s oil, acrylic, mica, pulverized marble, ink, graphite and pastel in these paintings, including luminous and metallic pigments.

What effect does that intend?

I hope my paintings feel as if they could be turned on and off. As if you have just a nanosecond ago pulled the plug on an old TV. The images look unstable, as if part is missing or out of focus. That echoes how, when I was a kid, US TVs only had 525 lines. Now, of course, we live by these glowing screens: it’s as if we have a doppelgänger which has another life, who lives in the screen and thinks everything is real in there…

You have a background in film, but I think it’s your photographs which provide your starting points?

Yes, looking back over the last few hundred paintings (see enaswansea.com) they feel like frames from a film which cannot be made. I’m revisiting things which I haven’t quite figured out. But I don’t shoot much moving stuff – rather, I have a library of 165,000 photos organized by ideas, sometimes literary, sometimes particular subjects like “pollarded” trees. They look weird to an American, we don’t control our trees like Europeans. To me, they become anthropomorphic.

What places are we seeing?

Many different locations, for example the North Carolina woods where I grew up, and the ocean near LA, as well as New York. People have said, though, that they are all infused with an urban feeling, even when they are landscapes. I’m not sure how that happens, but you could say that Frank O’Hara’s great poem ‘Meditations in an Emergency’, 1957, catches the mood: ‘One need never leave the confines of New York to get all the greenery one wishes—I can’t even enjoy a blade of grass unless I know there’s a subway handy’.

These works were made while you were locked down in New York. How did that influence them?

I think they benefited from the isolation. In New York life just collapsed, there was nowhere to go and time crawled by… The studio was – technically speaking – the same, but it felt very different…. And that affected what I was doing, and for me it made the paintings talk about time.

Are there also political aspects to that difference?

I think so, yes. Lockdown made us realize together – collectively, wordlessly, like bees communicating in a hive – that we are vulnerable. I think that made it clear that a lot of work is needed to make things more balanced in society. I’m a Southern woman who was indoctrinated in Victorian values that resist being too explicit about such matters, but in a strange way I think that’s in the show.

I was particularly struck by ‘area code 2019′. What’s happening there?

You could say that dropping a phone booth into this location makes no sense, but I’m drawn to phone booths as a plot device – miniature stages, places where superheroes go to get transformed… I started to take photos of them, but they’re vanishing – apparently only four working phone booths remain in Manhattan. I got the idea of small child – not really old enough to make a call – trying to use a phone booth at night in the woods, leaving you to wonder what the problem might be. It’s a mysterious painting of something you’ve never seen – yet feels familiar.

https://paulsartworld.blogspot.com/2021/12/interview-of-month-with-magnus-plessen.html

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

In this composition, ambiguity about the time of day hints at the disparate sources from which the artist drew. Swansea’s process begins by perusing the more than 80,000 digital photographs she has taken with an iPhone and archived on her computer. This painting unites some of her interests: the once ubiquitous phone booth, the deciduous forests of the eastern United States, an abandoned NASCAR racetrack in North Carolina, and her son, the child in the booth. As she shared recently, she starts by looking at photographs on the computer monitor and “stays in that world until it becomes clear to me what the image will be. Only then is it translated out of the digital realm into the studio.” She does not directly copy the photographs onto the canvas; instead, they serve as a digital mood board, stimulating her mind and guiding but not dictating how she paints.

- Made by Hand / Born Digital, 2024