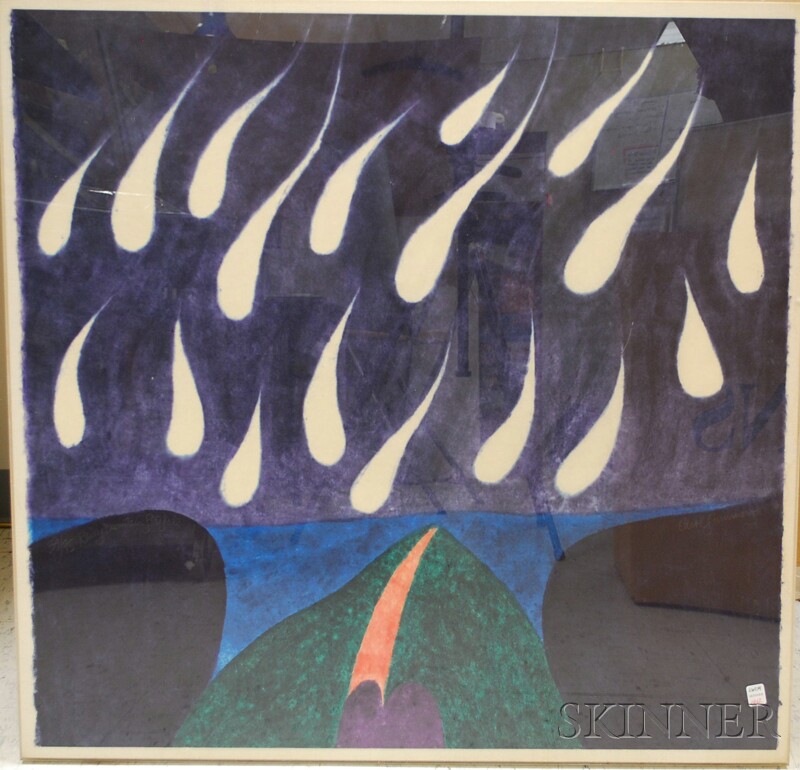

Carol Summers

American, 1925-2016

Rainy Mountain - Starfall, 1975

woodcut

SBMA, Museum purchase with funds provided by the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Contemporary Graphics Center and the William Dole Fund

1976.23.3

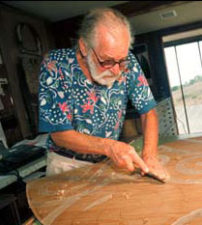

Summers in Santa Cruz studio, 1999

This print is from the mid-seventies. It's called "Rainy Mountain Starfall." It relates to a legend of the Kiowas. The Kiowas saw themselves as having reached their - the apogee of their power about the early part of the last century. It seems that in 1832 I think it was - it might of been '34 - there was a particularly wonderful display of shooting stars. And the Kiowas saw that - were struck by the grandeur of the display that year - and associated it with the height of their power. It was just at the time when they had amalgamated their empire - it was in Oklahoma - and just before the arrival, of course, of the white man, which of course, destroyed them.

- On a rainy November Saturday in 1984, people from around the Northwest came to Seattle to see the California artist, Carol Summers, making a woodblock print. This is the description he gave during a slide presentation of his work.

POSTSCRIPT

For an explanation of technique and interview check out this website:

http://printmakingworld.com/emeralda/vi/viprod/VT/print/transcripts/vtsum.HTM

Summers in his studio at work, 1999

COMMENTS

Carol Summers is renowned for his vivid colors and the revolutionary woodblock techniques he introduced in the 1960s. In the course of printing he frequently used solvents to transform the pigments into dyes, which then tend to penetrate the paper and result in a watercolor effect. This allows for rich colors and soft blurred edges. Although his work is traditionally known for its big, bold, beautiful forms and joyous colors, these saturated colors and exuberant shapes can also be effective in expressing contemporary issues. For his subject matter, Summers drew from a variety of countries and cultures, both exotic and local, and reflect his extensive travels abroad and around his home state of California.

American artists have had a long history of creative works on paper, including watercolorists, printmakers, collagists, bookmakers, etc. During the last 50 years especially there has been a strong revival of interest in the woodcut. Among the very best practitioners of the color woodcut and surely the most consistent as well as persistent of all is Carol Summers. Deeply involved in his preferred medium, he has brought to it a passion and artistry of a very high order.

A love of color, often high-keyed and richly saturated, its expressiveness and above all its power to evoke rather than depict or narrate something literal or specific. The color he chooses, like the man himself, is direct, forthright, and clear. While his works are joyous and generally life-affirming, color chords at times may be strident and off-putting or uncanny, at time mysterious. His deep blues can convey a gravity of emotion as for example in Sunset after Storm 1988 or Night 1996. Summers uses color daringly and, like Pail Klee whom he admires, he is a modern fabulist of the imagination.

Summers' prints are frequently large - very large as woodcuts go. He obviously is not afraid of hard work, doing the cutting, coloring and printing himself. His prints resemble the stuff of dreams, but the man himself is fully alert. He is technically expert and has developed a personal way of coloring and printing. Well traveled, well read, cultivated and witty, he creates works that spring forth from specific places or historical events, utterly transformed. His love of non-western art shines through.

-Matt Phillips, from Carol Summers Woodcuts

Woodcut artist Carol Summers looks at life with a worldwide perspective

By Rob Pratt

THE WOODCUT PRINTS of Santa Cruz artist Carol Summers have a way of haunting you--the rolling forms and vibrant colors flash in your eyes long after you see them.

That's what I think as I drive up Empire Grade past the entrance to UC-Santa Cruz and look west across grass-covered hills toward the ocean--or where the ocean would be if a thick fog didn't obscure the view. I know I saw those hills--but indigo or green instead of yellow-brown--somewhere among the prints hanging in the Museum of Art and History's Solari Gallery as part of a 50-year retrospective of Summers' woodcuts.

Or maybe not. I drive farther into the hills and deep into the redwoods atop the mountains along the county's North Coast. The towering shapes, the canopy lowering on mountain canyons, the sheen of drizzle on a snaking road. All of these images flash back to the woodcuts I saw--but something's different. The color's not exactly right. And the experience of it--a fleeting charge of the moment--feels different than the ground swell of timelessness in Summers' seemingly age-old scenes.

"I didn't understand what a trickster he is until we put this show together," MAH curator Kathleen Moodie tells me later. She's talking about his technique, the way he prints on both sides of the paper, smears ink and deeply saturates colors to fool the eye. But, I think, he's also a Zen-like trickster, a not-teacher who shows you that you can't always believe your eyes, that there's more to life than the individual and that the world changes every time you look at it--unless you look for the long view.

There's no way that Summers could have planned the lesson when I drove up to his mountaintop studio, but he stood there watching when I learned it. Or rather experienced it. Days later I stopped to think about that seemingly insignificant moment and learned that my eyes had fooled me.

I had come up the driveway that circles his studio, driving around to a cluster of cars. The odd-shaped gap amid them seemed far too narrow for my Chevy Cavalier, so I circled around again, stopped in the middle of the driveway, left the car to meet Summers at the door to his studio and apologized for my parking job.

"Oh, there's plenty of room," he said, ushering me back outside.

I got into the car, backed to the spot and miraculously angled between a mini-truck and a Honda with ease. Watching from atop a rock wall, Summers declared, "Yards to spare!" as I climbed out of the car wearing a sheepish grin.

Seeing Isn't Believing

SUMMERS, 73, wiry and white-bearded, is a quiet man (written in 1999). The fog outside and hushed symphonic music from a radio tuned to KBOQ at the far end of the studio only underscore the point as he shows me around. His studio is a weathered place, the wooden structure brown-gray from the seaside air. Inside it's more like the eye of a storm than the tempest. The world may whirl around outdoors, but the studio is obviously a place of repose and focused concentration.

Summers comes off as quiet not from shyness. He easily talks of his techniques, why he favors Japanese paper (for tactile qualities and the way it absorbs ink) and where his imagery comes from (folk arts of the world). Instead, he chooses words carefully because they can limit true understanding: they're specific, narrative and inextricably intertwined with emotion--and they mean different things to different people.

"I see my work one way--my eyes lie on the outside, and what I see doesn't strike me as unexpected," he says. "If there's something else in it, you bring input to it when you look at it. And sometimes a person's experiences might blind them to what's there."

It's a difficult question for him. I asked what his works mean--what ideas he tries to express. He growls and sits forward before answering, and I get the impression that I missed the point.

"I don't feel very compelled to define that in advance," he explains. "So I'm often surprised at the response of others. Certainly I've found some works are more popular than others, but I can't say why."

Maybe that's the point I missed. His works draw on epic landscapes and centuries of tradition--scenes and experiences from his world travels and images drawn from the folk arts of the many places he has lived. Individual events and points of view come up in his pieces, like The Grave of Santa Ana's Leg (1992) or Fontana (1965) and Basholi (1980), but generally his works are more concerned with geologic time than human history.

"Humans are a tiny little family looked at from a geologic point of view," he says. "I don't look at divisions as all that striking--not as much as the similarities. I look at all of mankind as if we're one body. Sometimes we can only focus on the differences, but we're 99 percent the same. We're living in a time when there aren't too many secrets as far as the diversity of the world."

A World of Colors

BORN THE DAY after Christmas in 1925, Summers grew up in Woodstock, N.Y., and, after a four-year stint in the Marines during and after World War II, studied painting and printmaking at Bard College. Soon he traveled to Italy, moving his studio there on a grant from the Italian government in 1959, to India and, later, to Mexico. All of those places--and all of their traditions--have left their mark on his work.

"You can see that he bursts into reds and oranges when he gets to India," Moodie says, showing me around the MAH exhibit.

"I put these two a little closer together than I usually space things because they're essentially the same fountain," she continues, walking up to a pair on a far wall, Fontana (1965) and Dream (1966). "This one [Fontana] looks like he's there in Italy looking at the fountain, and this one [Dream] looks like he's doing it from memory. It's darker, and the shape of the trees is changed."

Works completed after his move to Santa Cruz in 1972 have mountainlike horizons and dark, starlit skies. His colors are earthy, heavy with blue and green and frequently jarring with splashes of red and yellow.

It was in Santa Cruz that he met his second wife, Joan Ward Toth, a textile artist. They married in 1973.

MAH director Chuck Hilger met Summers shortly after he came west from New York City. It was through Joan that they were introduced--Hilger's children went to DeLaveaga Elementary with Joan's.

"I thought, he's got to be a good guy if he's with her," Hilger says. (Moodie explains that Hilger has wanted for years to mount a major retrospective of Summers' work at the MAH. The 50-year anniversary of his art-making provided a "great opportunity.")

With Joan, Summers once traveled to Mexico in search of a traditional potter and ended up buying a hacienda, which they converted to a bed-and-breakfast still open in Guanajuato.

"We needed a house in Mexico like we needed a hole in the head," he says. "But we fixed it up and turned it into a B-and-B that became Casa de Espiritus Allegres, the house of happy spirits. I moved my studio down there. Joan was a weaver, and Guanajuato was a weaving village, so she taught the weavers there her techniques and would buy weaving from them and dye it."

He smiles when I ask if they still live together. "She died last year," he says, and I don't follow up the question.

It's Moodie who hints at the deep personal effect of his loss. The final work in the show, hung just inside the double-doors to the Solari Gallery, is titled Farewell (1998) and shows a simple, wide line crossing a hill-like expanse toward a sunset-red horizon. It's one of the few pieces in the show not titled after a place, she adds.

Places, however, aren't the key to understanding Summers' woodcuts--even though they do hint at the underlying theme. Most important are the roads between the places, the stories of the people of the world, the artful solutions to problems of personal expression and the experiences of a lifetime instead of the aggregate product.

"Not only does he make art that has other pieces of the world, but he travels constantly--he's a walker, a trekker," Moodie says. "He goes to the places he draws from, and he brings it all together in his woodcuts."

For Summers, the journey isn't his alone. It's a road that all of humanity travels, an easily recognizable thoroughfare. Moodie says that local museum visitors and tourists alike easily understand the themes of Summers' prints. A class of Japanese students summering in Santa Cruz as part of a UC Extension program, she adds, found the prints particularly amazing, and one of the group penned a telling remark in the gallery's guest book:

"I love around the world people," reads the note, signed only "Masai."

Carol Summers Woodcuts: 50-Year Retrospective

Museum of Art and History, Santa Cruz

From the August 18-25, 1999 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.