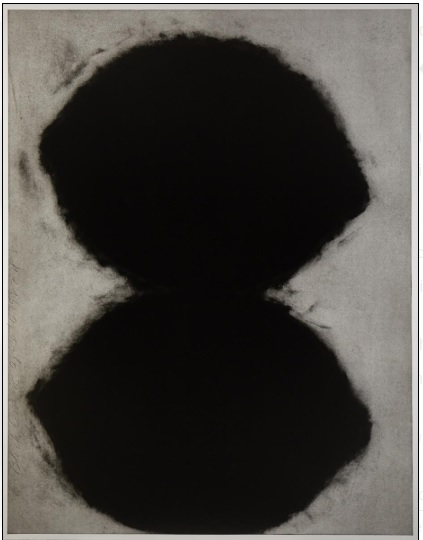

Donald Sultan

American, 1951-

Black Lemons, 1987

aquatint, ed. 7/14

63 × 49 in.

SBMA, Gift of Martha and John Gabbert

2016.18.5

Donald Sultan - undated photo

"Artists don't compare themselves to each other based on money. Nobody really knows what money other artists have. They don't care that much. The measure is the work and how you think your work is perceived. How the museums are. How you are doing."

- Donald Sultan

The artist working at Jeryl Parker Editions, New York, December 1984. Photo: Brenda Zlamany

COMMENTS

To the beholder, the whole world suddenly seems to be full of lemons. Somehow, they are magic, these lemons, like a Christmas tree all lit up with real, white candles and silver blown-glass bulbs: you look at them and see again with a child's eyes. Here they are, huge, covering the wall from the ceiling to the floor; there are only six aquatints - but they are monumental. Gorgeous, fat, velvety black, with those hazy out lines, the lemons are as powdery as if they had been covered with some mysterious kind of black icing sugar. The room is swarming with black lemons: one is floating, fat and zeppelin-like, in the middle of the print; another one decided to go a little higher up wards toward the sky, while a third, rougher and heavier, seems to swim underwater like a monstrous submarine. Then two lemons, careful not to touch each other, nearly fill up the space of the print. Further on there are two groups of three lemons each: one group tries to escape from the print, going up like balloons bunched together into a dark, solidified mass, although you somehow know they are all alike- same shape, same size. They are a bit weird: are they simply a family, or the rear of a host rising into the heavens? The three others are heavily settled, heaped into a fat pyramid, one of them nearly shoved out of the ground of the print.

A "vision" is something seldom achieved today, especially in printmaking, where technical minutiae very often seem to hinder the stream of creativity. To feel happy looking at Sultan's Black Lemons there is no need to analyze or to go fishing in a bog of cultural references, no need to ponder the labels, schools, or "isms," as Donald calls them, that feed the maniacal modern craving for classification. It is only pleasure; and one realizes one has a happy smile on one's lips and in one's heart. Of course the pleasures of the imagination are not for everyone. Some people never look at the bunches of multicolored balloons when they bump into them at the next corner, never fancy them flying away, perhaps carrying along the old vendor, right up into the sky. Some people never see the flowers. The Lemons are not for them.

There is an old guessing game called "Si c'etait" ("If it were"). Surrealists loved it. For me, Sultan's Lemons, "if they were flowers," would be those enormous Chinese poppies (if by some miracle you could happen to be there on the June morning when they have just been unfolded by the sun in their full, new glory). Those huge Asiatic flowers are twelve inches across and lacquer red, with a satin-like bright black star in the middle; the little "Chinese head" within the blossom is fringed with a ruff of pistils powdered with a sooty black dust, which, in slowly dropping down, darkens still more the heart of the flower. Perhaps, for me, this black dust is what links the miraculous and perfect poppy to the Black Lemons. A close look reveals that the empty field of the print is also powdered, with tiny aquatint particles: indeed the small, erratic spots give to it a mystery, a kind of organic depth, which attaches the lemons to the ground. If you tried to lift one of them out of the print, all would come away together: the lemon, its powdery outline, but also the black dust of the background.

Out of the blue, a name comes to mind: Seurat. In Seurat's conte-crayon drawings, the subject and the background are sealed together by that hazy mist of remnants of crayon which cling to the uneven surface of the laid paper. The same kind of effect can be seen here, but created only by the dust of aquatint particles which escaped, like sand blown by the wind. One thinks of those pure black shapes on a nearly blank background, for instance the "Femme au manchon", or the studies for the dog and the monkey in "La Grande Jatte". The paper is irregularly tinged by the smooth crayon. There too, the outlines are hazy yet sharp, a kind of shadow theater. "The art of deepening surfaces," Seurat said. The lemons spring out of the background, but, somehow, it is possible that here, also, there is an art of deepening surfaces.

There is no doubt, the use of black and white is a success: something sensual, a pleasure which sweeps away the too familiar and the feeling of being blase. Here, the interesting thing is also that the pleasure of looking at the prints rids you for a moment of intellectualism - that octopus, stickier than the tar on the beaches, which grips you all your life. Of course, you do eventually resort to your own bundle of civilization - your baggage of ready-made images, worn-out sentences, coded reflexes, and so on - but at first sight, Donald's Lemons don't immediately switch on the whole machinery; you are only happily filled with the image, its strength, its richness.

Obviously, one lemon alone, two lemons with a distance between them, or three lemons touching allude to a single person, a couple, a classical triangular relationship, fertilization, and so on. Of course, the Lemons look like full and generous bosoms. Of course, the artist himself, when doing them, had his "pack" on his back, his own bundle of images, references, reading; concocted and seasoned perhaps in slightly different ways, it is common to all of us. What makes the "difference" is the "how," the form, the style. To put it simply, it seems to me that the Lemons have that original character which makes a true work of art. Repeating old myths, old images, they somehow do so in a different language, and bend them a little in a new way.

When I happened to bump into the Black Lemons, in Paris, I have to admit that I knew nothing about Sultan. I went to see him in his down town New York studio and again in Signac's Saint-Tropez studio, which Sultan takes each year for the summer. (The result was a gift to, and an exhibition in, the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris.) In the Saint-Tropez studio there were drawings of lemons, and paintings. I find it rather difficult to talk with an artist: it should be his work itself that speaks to you; that should be enough. The artists nowadays spout a lot. Sultan did not. He was busy painting or drawing; we would exchange a few words from time to time. It is better like that: you can look freely, without being given the "directions for use."

Hanging on the wall in front of him there was a poster with an enlarged Signac drawing, one of those where he is trying to imitate Seurat's manner. The background, exaggerated by enlargement and poor reproduction, had the same speckled aspect the Lemons have. To my unnecessary question Sultan replied, "Of course I was influenced by the Seurat drawings: they are beautiful." Better to be told, any way, and to check one's own feelings.

What I learned in Saint-Tropezis how the Lemons are created. The beginning of the story lies in some tulip drawings, made with crushed charcoal; their outlines, firm but hazy, even foggy, were loaded with charcoal dust. In order to achieve the series of 1983 Black Tulips, Sultan had developed a trick, a "knack": covering the copperplate uniformly with resin particles, then blowing away the excess grains by using a glass pipe, revealing the shapes of the tulips. But because the resin dust was loose, the copper plate could not be handled before it was heated, before the grains were fused onto it. And with the Lemons project, there was a further problem: the prints' size (62 by 48 inches!) made it very difficult to move the plates without disturbing the resin dust. The printer, Jeryl Parker, had to re-do his whole workshop. The plates were laid flat on a hot table, the kind restorers use to reline a canvas. A rail system allowed the plate to go in and out of the dusting box without any handling, to keep the resin articles at rest.

Before beginning the process, Sultan would draw the shape of the lemons on the copper plate. Once the plate was uniformly grained, as with the Black Tulips, he would blow away the resin powder around the drawn shapes using a long tube. The edges would then be softened by using a Japanese brush. This kind of sand drawing being finished, the resin particles would be fused onto the plate by heating it without ever touching it. Then the plate would go directly into the acid bath: open bite, without any stop-out. Some particles of resin inevitably would be left over on the background; furthermore, while blowing, Sultan would spit a little here and there. This gives to the printed impression a hazy background, as well as the imperfections which are purposely left there.

It sounds easy and simple when you describe it. The idea actually is simple and the process, fascinatingly thrifty. Nevertheless, a real mastery is needed, and subtlety from the artist as well, as from the printer. The beautiful results hang here.

Something has still to be said: where did that lemon obsession come from? In 1983, Sultan had made the Tulips; in fact, they are not real tulips but the streetlights in New York, which, for him, were big-city tulips. Then, he went to see the Manet exhibition in The Metropolitan Museum of Art and stopped dead at the small single lemon, the one which once belonged to Dr. Proust and which is now in the Musee d'Orsay. The perfect shape, the simplicity, he says.... He began to draw and paint lemons. But he soon understood that the thing he had in mind was an industrialized thing, like his Factories, like his street light-tulips: standardized lemons, products of the terrifying consumer society; lemons you really cannot fancy as, once, hanging on a real lemon tree, in a real garden; lemons you can see only under plastic in the supermarket or already cut into halves on restaurant tables; graded lemons, each of them exactly like the next—same size, same weight, same color, same shape. You buy them by the piece, like cans. For Sultan, if I got it right, they are no more related to Nature than are the Jasper Johns ale cans. Sad lemons, these, the only ones available for the children of the cities. Their strangeness, nevertheless, is brought home to you afterward. It is like an aftertaste. It is something which gives a deepness to the clear, childish, sensual pleasure that comes first. The most solar of all the fruits is here bright black: voluptuous darkness. The most refreshing of all the fruits, here, looks a little like a choke-pear. Death and delight, pleasure and sadness. But it is only with a great modesty that those concepts ooze out of Sultan's Black Lemons: could it be one of the secrets of their achievement?

Donald made for himself a gauge, a pattern of a lemon, in paper. Both drawn and printed lemons are doomed to go through the test of that gauge, which inevitably defines their size and shape. It is only the placement that changes. It is only the dust of crushed charcoal or the residue of resin particles which later, in the process of their fabrication, gives again to them the scantist minimum of individuality that still baffles the rule, with fruits and with men alike. Both men and lemons are minutely defined by their "function"; tools, in short. Sultan, anyway, sees them like that.

As a printmaker Donald Sultan's career is still very short. One can wonder if the monumental Black Lemons are some kind of prompt miracle. If not, we can hope they are only opening the way for other things. There is hope here, a most unusual hope. The technical craftsmanship of the artist should allow him to surprise us again.

- Brigitte Baer, Donald Sultan's Black Lemons, © The Museum of Modern Art, New York, February 4, 1988

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Recognized for his use of unconventional materials and celebrated for his still lifes depicting everyday objects, Sultan began painting lemons in 1983. After creating a series of charcoal drawings on the subject, he produced a number of monumental aquatints. The result is a powerful depiction of the familiar yet abstract shape of a lemon that feels at once recognizable and mysterious.

- In the Meanwhile, 2020