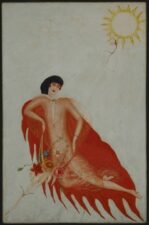

Florine Stettheimer

American, 1871-1944

Journey to the Sun, 1927 ca.

oil on canvas

58 × 33 1/4 in.

SBMA, Gift of the Estate of Ettie Stettheimer

1958.15

Florine Stettheimer - Self-Portrait with Paradise Birds, detail, oil on canvas, n.d.

“I was pure white

You made a painted show-thing of me

You called me the real-thing

Your creation

No setting was too good for me

Silver--even gold

I needed gorgeous surroundings

You then sold me to another man”

“The Unloved Painting” poem by Florine Stettheimer (McBride, p. 51)

RESEARCH PAPER

The art of Florine Stettheimer is undeniably complicated regarding style and subject matter. Her paintings have been characterized as Camp (Nochlin, p. 67), feminine and fragrant and highly decorative (Bloemink, “The Life and Art of Florine Stettheimer”, p. 125). These assertions are rather limiting in nature, and do not allow for a full understanding of Stettheimer’s artistic practice. She was born into an upper-class New York family in 1871 and spent many of her early years in Europe receiving a privileged art training prior to World War I. Upon her return to New York, she was an active participant in the burgeoning avant-garde art movement in New York. As a result, her paintings are often intricate, highly constructed images relative to the concerns of modern life between the wars.

“Journey to the Sun” is an oil on canvas painting completed by Stettheimer around 1927. The focal point is a large, centrally placed bouquet of flowers floating against a flat background. The stems of the bouquet direct the viewer’s eye diagonally across the canvas from the lower left edge to the upper right edge in which a dragonfly floats towards a partially visible sun. In the upper left are a pair of large wings, also partially cropped, that blend into the light blue and white background. The subject matter is familiar, yet it is presented in a unique and whimsical style. The imagery is large in scale and placed into shallow space. The scale and lack of depth is both disorienting and intimate emphasizing the fantastical qualities of the image.

The use of color organizes and unifies the painting. Stettheimer’s palette often included layers of highly saturated colors adding an aspect of artifice to her paintings. Such lavish paint application is particularly evident in the large red, pink and yellow flowers. Each of the three flowers consist of gestural brushstrokes of numerous hues, and the impasto adds to the striking quality of this work. Such dramatic swirls of color appear theatrical and give an expressive quality to the flowers reminiscent of the color combining found in early paintings by Matisse. The painterly quality of the three central flowers contrasts with the small light pink flowers and the diaphanous dragonfly which are painted with thin, more translucent washes of colors.

Stettheimer, along with other modern artists, philosophers, and writers, was very interested in exploring theories of identity, especially theories that emphasized the intangible aspects of identity. She painted numerous portraits and self-portraits during the 1920s that utilized specific visual symbols to represent the mutable aspects of the sitter’s identity (Bloemink, “Florine Stettheimer: A Biography”, p. 214). In 1923, she painted “Portrait of Myself” in which she depicts herself as an artistic seer, floating in the sky beyond the earthly realm, and she employs similar motifs to those in “Journey to the Sun”. Stettheimer wears an artist’s black beret and a diaphanous dress with a wing-like cape. Her eyes are large, outlined in red, and she gazes directly at the viewer as if in a trance. She holds a bouquet of flowers while floating toward the sun and is joined in the sky by a dragonfly whose thin, curved body mimics the artist’s form. The title perhaps refers to Stettheimer’s favorite author Marcel Proust and his concept of the “different self”. The goal of the different self was not to provide a narrative, but to breakthrough to a deeper more human self (Bloemink, “Florine Stettheimer: A Biography”, p. 236). Like “Journey to the Sun”, the forms freely float against the flat background devoid of any clear reference to time or place.

Bloemink describes the art historical iconography of the butterfly and dragonfly as “symbols of metamorphic transformation and concepts of the feminine” (“Florine Stettheimer: A Biography”, p. 236). Stettheimer saw the dragonfly as her alter ego and she often described herself as an éphémère, which is French for short-lived and refers to short-lived insects like the dragonfly. Stettheimer made up a word for the éphémère – “the flutterby” - and she wrote several poems about the flutterby focused on their short life and impending death:

“An Ephemère:

I broke the glistening spider web

That held a lovely ephemère

I freed its delicate legs and wings

Of all the sticky, untidy strings

It stayed with me a whole summer’s day

Then it calmly simply flew away”

(Bloemink, “Florine Stettheimer: A Biography”, p. 237)

Like the dragonfly, Stettheimer was deeply interested in flowers. She painted many still lifes with flowers throughout her life, and she often arranged extravagant bouquets for parties. On her birthday every year she would gather herself a bouquet which she called an “eyegay”. The “eyegay” is a play on the term “nose gay” which refers to small bouquets that smelled sweetly and were given as delightful gifts. For Stettheimer, an eyegay is not an olfactory delight, but a short-lived, visual delight that pleases and intrigues the eye.

Dragonflies, flowers and identities are ephemeral and in flux. Stettheimer’s visual motifs offers a challenge to the notion of the traditional singular self; the “different self” is fluid, shifting and transitory. In “Journey to the Sun” and “Portrait of Myself”, everything is moving toward the sun, and close to being burned or consumed further emphasizing temporality. The wings in both paintings perhaps reference the downfall of Icarus who flew too close to the sun.

Stettheimer’s interest in the temporal and transitory emerges from her personal experiences. In 1914, while living with her mother and sisters in Europe, she and her family were forced to flee due to the outbreak of WWI. Stettheimer was deeply affected by the plight of war refugees and upon her return to New York, she vowed to be democratic, liberal, and modern. She identified as a “New Woman”, and due to her financial independence, she could live free from societal expectations and consider artmaking as a career (Bloemink, “Florine Stettheimer: A Biography”, p. 95). The artist Marcel Duchamp became a close friend, and they mutually influenced one another with the shared belief that the artist’s role is to provoke sensations of a more authentic self. As the writer Gertrude Stein commented “instead of projecting one forward in time to a single resolution, a modern narrative should force one into the fullness and depth of each moment and should proceed as a succession of such moments” (“Florine Stettheimer: Manhattan Fantastica”, p.72). To this end, Florine Stettheimer developed a unique visual language to emphasize the intangible nature of identity.

Prepared for Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Elizabeth Russell, February, 2023

Bibliography

Bloemink, Barbara. “The Life and Art of Florine Stettheimer”. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995.

Bloemink, Barbara. “Florine Stettheimer: a Biography”. Munich: Hirmer, 2022.

“Florine Stettheimer: Manhattan Fantastica”. Exhibition Catalogue. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1995.

McBride, Henry. “Florine Stettheimer”. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, distributed by Simon and Schuster, 1946.

Nochlin, Linda. “Rococo Subversive,” “Art in America” 68 no. 7 (September 1980) pp. 64-83.

Florine Stettheimer - Portrait of Myself, 1923, oil on canvas

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

The unforgettable and always original Florine Stettheimer recently enjoyed the attention of a retrospective exhibition at the Jewish Museum in New York; a fitting repetition of the same honor that her close friend, Marcel Duchamp, helped to organize at the Museum of Modern Art right after her death at the age of 73. Interestingly, although she continued to paint throughout her lifetime, she chose never to exhibit her work in public after its tepid reception in a solo show held at Knoedler Gallery in 1916. Instead, her paintings were bestowed upon friends and family as gifts, or made for her own personal pleasure alone. That is likely the case in the instance of this flower picture, which may be one of the series that she produced upon the occasion of her birthday. She called these pictures “eyegays,” a reference to their visual rather than olfactory interest, as in the small bouquets of flowers known as nosegays. The fantastical ascent of these fading flowers, powered by angels’ wings and led by a dragonfly is typical of Stettheimer’s whimsy, as is the faux naiveté of its childlike execution. Famously, Stettheimer was named by Andy Warhol as his favorite artist -- a choice one well understands given their shared understated sophistication.

- Preston Morton Reinstallation, 2022