Jesús Rafael Soto

Venezuelan, 1923-2005

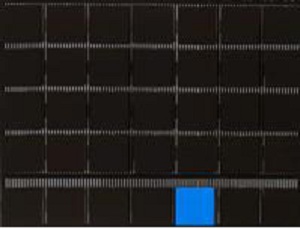

Homage to the Human Being (An American Portrait, 1776-1976, series), 1975

wood and aluminum, ed. 18/25

19 3/4 x 26 x 5 in.

SBMA, Gift of Transworld Art

1976.49.7

COMMENTS

Movement, Style, School or Type of Art:

Though most frequently associated with Op Art, Soto was, more precisely, a Kinetic artist. His works were meant to display not only the implied movement of Op, but also the actual movement Kinetic Art provides by allowing the viewer to participate, or "move through" the piece.

This was especially notable in his Penetrables series of the 1960s, where spectators were invited to walk through lots of hanging nylon filament line.

Soto is also rightly linked with the Geometric movement in Venezuela.

Born in 1923, Ciudad Bolivar, and trained in his native Venezuela, Soto's early influences were Cubism, Cézanne and Mondrian. It wasn't until he moved to Paris, in the 1950's, that he found his true calling in geometric art. (It probably helped that he also met kindred spirits - Victor Vasarely, for one - in Paris.) Besides his Kinetic works, Soto is best known for his use of modern materials such as nylon filament thread, metal rods, steel, aluminum, perspex (transparent acrylic resin) and industrial-grade paint. Energy is one of the most striking elements of Soto's work and his experiments with optical effects are representative of some of the most successful of the Op Art-Kinetic Art movements. Soto's work, however, surpasses the mere exploitation of optical effects and he presents in his paintings a concentration of energy which attain a point where the paintings become a mirage, kinesthetically like a mental tension.

Soto's use of the moire effect plays a prominent role in his early works of transition from the tradition of hard-edge abstraction founded by Mondrian to the more fluid expression he presently uses. The influence of Mondrian's balancing of lines and composition can be found in Soto's work, with Soto's added touch of a personal search for an art which would be its own master, wholly independent of the natural world, an attitude reflective of Mondrian's.

Soto's work with identical and multipliable elements was aimed at reducing the sign to total anonymity, in the effort to get away from subjective art. When the transition to kinetic art came Soto's way in 1955 he began to make plexiglass superimpositions. Spirals traced upon perspex were superimposed in depth. The optical effect that resulted was in the relationship between the surfaces. Soto's painting began to emerge and assume a sculptural dimension when he suspended wire and rods of metal in front of the background. This striping of the background seems to create the effect of attacking and partly absorbing the forms which are placed in front of it. Soto's work established a concrete relationship with the viewers perception as disconcerting and fascinating as a mirage.

In 1973, the Jesús Soto Museum of Modern Art opened in Ciudad Bolívar, Venezuela with a collection of his work - a large number of the exhibits are wired to the electricity supply so that they can move. The Venezuelan architect Carlos Raúl Villanueva designed the building for the museum and the Italian op artist Getulio Alviani was called to direct it.

Some of Soto's work adorns the ceiling of the main hall of Caracas' arts centre, the Teatro Teresa Carreño.

Jesús Rafael Soto died in 2005 in Paris, and is buried in the Cimetière du Montparnasse.

http://www.rogallery.com/Soto_Raphael/soto-bio.html

http://arthistory.about.com/cs/names_ss/p/soto.htm

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Beginning in the 1950s, Jesús Rafael Soto carried out experiments in geometric abstraction and Kinetic art that established him as one of Venezuela’s leading modern artists. The artist’s fascination with actual and perceived movement is apparent in this work in which black squares are placed a few inches in front of a ground of parallel black and white lines to create a flickering effect as the viewer’s eyes move across the work. Despite their hard surfaces, the visual effect produced seems to dematerialize the forms—transforming them into a complex patchwork of light, color, and space. The artist believed that “The immaterial is the sensitive reality of the universe. Art is the sensitive knowledge of the immaterial. To be aware of the immaterial in the state of pure structure is to cover the last stretch of the road towards the absolute.”

One year after his first retrospective exhibition at the Guggenheim in New York in 1974, Soto produced Homenaje al humano for a three-part portfolio titled “An American Portrait, 1776-1976,” organized to celebrate the United States Bicentennial. Soto’s work, and others included in the portfolio titled “Your Huddled Masses,” dwells on the role of the foreigner and his struggle for freedom, dignity, happiness, and identity. This sense of adversity is manifest in the single bright blue square in a homogenous sea of black.

- SBMA title card, 2013

Beginning in the 1950s Jesús Rafael Soto carried out experiments in geometric abstraction and kinetic art that established him as one of Venezuela’s leading modern artists. While working in Paris during the mid 1950s, Soto became interested in Marcel Duchamp’s optical machines because of the ideas they embodied and their ability to move.

- SBMA Wall Text, 2000