Portrait of Mexico Today: A Resource for Students and Teachers

Preserving a Masterpiece (video 29:49)

David Alfaro Siquieros

Mexican, 1896-1974 (active USA)

Portrait of Mexico Today, 1932

fresco on cement

99 x 384 x 100 13/16 in.

SBMA, Anonymous Gift

2001.50

Siquieros at age 42

"The mural is a wonderful gift." said Robert Frankel, executive director of the Santa Barbara Museum of Art (2001). "It's an astounding object in wonderful condition."

"To have [a] mural of such importance that has never been seen before put before the public is amazing," said Luis Garza, who studied the work from 1993 to 1996 when he was the Getty Conservation Institute's community liason in the restoration of a Siqueiros mural at Olvera Street in downtown Los Angeles. "That mural was the front-runner of his work that followed, a turning point. When I saw it, the pigmentation was very strong. The colors were vibrantly coming through."

RESEARCH PAPER

The Imagery and Aesthetics of David Alfaro Siqueiros' Portrait of Mexico Today, 1932

Portrait of Mexico Today, 1932 is one of three murals painted by David Alfaro Siqueiros while he was a political refugee in Los Angeles between April and November 1932. It is the only surviving intact mural in the United States by the world-renowned Mexican muralist. Street Meeting was destroyed due to the elements and Tropical America, due to its controversial subject matter, was whitewashed and left abandoned for decades until the J. Paul Getty Museum undertook to maintain it.*

Painted on the interior walls of a semi-enclosed garden structure in the private Pacific Palisades home of filmmaker Dudley Murphy, Portrait of Mexico Today, 1932, fortunately, escaped the ravages of protest and neglect. Cared for over the years by the Murphys and the successive owners of their home, this landmark artwork was generously donated to the Santa Barbara Museum of Art in 2001. Through the additional generosity of anonymous patrons, the Museum subsequently launched a major conservation effort with the express goals of preserving this historic work of art for future generations and making it available to the public for the first time ever. As a result, Portrait of Mexico Today, 1932 was moved intact, meaning the painting and the entire building in which it was housed, was moved from the Pacific Palisades.

Of the three murals painted by Siqueiros while he was in Los Angeles, Portrait of Mexico Today, 1932 is direct in its commentary on the social and political conditions in Mexico in the early 1930s. From a position of political exile in the United States, Siqueiros depicts his contemporary viewpoint of his native country and its relationship to the United States.

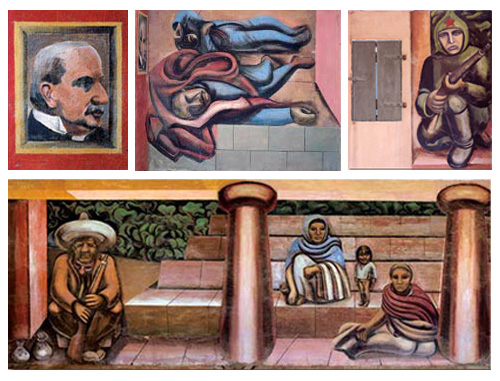

Central Wall: The long central wall presents the work's main tableaux, two Mexican peasant women wearing traditional rebozos (shawls) and seated on or near a stepped pyramid with a child standing between them. Taking advantage of the garden portico's existing architecture, Siqueiros framed this pivotal image between two painted columns that echo the two wooden columns that help support the structure.

To the left of the anguished women and child is a portrait of Plutarco Elías Calles, one of a generation of military generals who presided over Mexico during the Revolutionary Period of 1910-1940. A dominant force both in front and behind the scenes from 1924-34, first as president (1924-28) and then as Supreme Chief of the Maximato (the six-year period, 1928-34, during which Calles ruled unofficially from back rooms), Calles is seen wearing revolutionary garb, epitomized by the sombrero he wears and the rifle he holds perched against his knee. Next to him are moneybags, which bear, specifically, on the meaning of the mask that Calles has removed from his face, but left hanging around his neck.

Left Front Wall: Again, using the building's physical configuration to advantage, Siqueiros painted a portrait of the United States financier, J.P. Morgan, on the small wing wall opposite of Calles's portrait. As a result, the two portraits are in dialogue, even if Morgan's is in profile. The images themselves and their proximity reveal Siqueiros' interest in addressing the relations between Mexico and the United States in the early 1930s. At the heart of this relationship between the two countries was oil. Mexico wished to retain its sovereignty over oil, while United States wanted the Mexican government to protect the ownership rights of its businesses operating in the oil industry in Mexico. J.P. Morgan, a symbol of US commerce, is significant, because in 1927 Dwight Morrow, a senior partner in Morgan's famous financial firm, was appointed ambassador to Mexico. Siqueiros, as well as the Mexican government, understood this appointment to be another example of the United States financial community exerting pressure on Mexico in order to benefit economically.

Left Side Wall: Between the portraits of Morgan and Calles, Siqueiros placed two murdered workers, blood streaming from their mouths. By locating these corpses in between Morgan, a symbol of U.S. economic power, and Calles, a symbol of Mexico corruption unmasked, he dramatically expresses his view of the high social cost of the dealings between Mexico and the United States in the late 1920s-early 1930s. Originally a liberal, even a radical, Calles became increasingly conservative over his ten-year reign. As the years passed, he became less tolerant and began using the force of the military to suppress his foes. As a result, an increasing number of political prisoners began filling Mexican jails. In the case of Siqueiros, he was under house arrest in Taxco before coming to Los Angeles for an extended stay in1932.

Right Side Wall:Adjacent to a window with a wooden shutter that is part of the existing architecture, Siqueiros painted an image of a Communist soldier, kneeling with his rifle perched on his knee. By using this image, Siqueiros identifies the Mexican Revolution with the Russian Revolution. More specifically, Siqueiros calls attention to how Calles handled Mexico's relations with the Soviet Union. Proactive in supporting a growing labor movement within Mexico, Calles claimed that he was addressing popular grievances and, thus, felt that there was no need for a strong Communist presence within Mexico. Eventually, Calles broke off diplomatic ties with the Soviet Union, satisfying groups within the United States concerned about Communist activity in Mexico. As a member of the Communist Party in Mexico, Siqueiros opposed Calles' anti-Communist actions--including political persecution to which he was personally subjected--and was critical of the Mexican leader's growing friendship with the United States, represented specifically through the special relationship that he built with U.S. Ambassador Dwight Morrow.

Aesthetics: If Siqueiros believed in a modern, revolutionary art, he was equally committed to the modernist ethic of formal and technical experimentation. His period of political exile in Los Angeles marked the beginning of a relentless search for new mediums and methods intended to serve the social purposes of his art.

Siqueiros' restless experimentation included his use of new and/or unconventional materials. Conversations with the Los Angeles-based architects Richard Neutra and Sumner Spaulding convinced Siquerios that his mural painting should relate to the modern buildings being constructed in Southern California. Accordingly, Siqueiros' Los Angeles murals inaugurate his innovative use of cement rather than the traditional fresco materials of lime and sand. In preparing to paint Portrait of Mexico Today, 1932, Siqueiros, as in Street Meeting and Tropical America, applied a top layer of cement to the original plaster walls. He then painted the wet cement with oil-based pigments, which is counter to traditional fresco technique that uses water-based paints so that when applied to the wet plaster the paint dries within the plaster to become part of the wall. While Siqueiros applied the cement in conventional fresco fashion, adhering "giornato," or in other words an amount that he could paint in a given session before it dried, he ended up producing images that rest on the surface of rather than embedded in the cement due to the inability of oil to mix with water.

In creating his Los Angeles murals, Siqueiros also began exploring how the newer, modern mediums of film and photography might enrich his mural painting. Critical to this development in Siqueiros' work were the artist's lively conversations with the world-renowned Russian filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein, whom he first met while he was under house arrest in Taxco during 1930-32. Eisenstein's belief in the emotional and visual power of film and photography and the creative use of montage was central in the formation of Siqueiros' new approach to mural painting.

Aiming to emulate in mural painting the dramatic impact and scale of film, Siqueiros began using filmic and photographic devices in the making of his Los Angeles murals. In writing about Street Meeting at the time of its making, Siqueiros reveals how projecting the photographic image assisted in the process of underdrawing for the mural: "After making our first sketch we used the camera and motion picture to aid us in elaboration of our first drawing, particularly of the models." (Goldman article, 12) In a later statement, Siqueiros remarked "The still camera and the motion picture camera for the first time in history offer us...the subtlest and amplest elements of space, of volume in space, of movement in all its complexity." (Micheli book, 9) Siqueiros continued his use of photographic projection in his succeeding mural Tropical America. In her research of Portrait of Mexico Today, 1932, Shifra M. Goldman has shown that Siqueiros also used photography as actual source material, not only as a means for projection. She discovered that the artist based his painted portrayal of J.P. Morgan directly on a photographic portrait of the financier by Edward Steichen.

Among the other factors that make Portrait of Mexico Today, 1932, significant is that in this third and final Los Angeles mural Siqueiros attempts his earliest formulations of what he eventually called "polyangular perspective." Like other modernists of his generation, Siqueiros was responsive to modern physics, especially to the discoveries about the fourth dimension, and thus sought new artistic conceptions of space and time. Here, the example of Eisenstein and his use of the novel technique of montage proved instrumental. Portrait of Mexico Today, 1932, is a fascinating study in how Siqueiros begins these new spatial explorations. While the mural's forms are grandly simplified and made monumentally arresting, the composition they comprise can only be read and understood by viewing all of the painted walls, which requires moving around the architectural space and then synthesizing the distinct but interrelated sections to arrive at meaning. Like montage Siqueiros calls upon the viewer to synthesize disparate elements across time and space. Additionally, his treatment of the top edges and corners is an early effort at unifying mural painting with architecture by incorporating it into the building rather than merely applying it to a wall. In rendering architectonic forms and varying their angles along the uppermost reaches of the mural, Siqueiros aims to connect the ceiling with the walls. Similarly, he presents the central pyramid from multiple perspectives so that its base appears to join the actual floor. These deliberate connections between the painted walls and the ceiling and floor attempt to activate the physical environment; they are compositional inventions that Siqueiros fully develops in his next mural as a way of mirroring the dynamism of the modern age.

Portrait of Mexico Today, 1932, remains the legacy of an intense period of theoretical and practical experimentation for Siqueiros. It sets the stage for the artist's completely articulated use of "polyangular perspective" in his tour de force Ejercicio plástico (Plastic Exercise) painted in 1933, once again in political exile, at the Buenos Aires home of newspaper editor Natalio Botana.

*Los Angeles-based art historian and Siqueiros expert, Dr. Shifra M. Goldman, and Jean Bruce Poole, Curator of El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument, spent years trying to interest the community in saving Tropical America. Their pioneering efforts were eventually recognized by the J. Paul Getty Museum.

- Diana C. du Pont, Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, SBMA (2001)

POSTSCRIPT

Newspaper Articles published at the time of the mural installation at SBMA

"Work by Famed Mexican Muralist to be Preserved," by Keith Davidhamm and Susan Brenneman,

Los Angeles Times, August 22. 2001

A little-known Los Angeles art treasure--a monumental mural by David Alfaro Siqueiros, one of Mexico's most renowned and controversial artists--has been dontaed to the Santa Barbara Museum of Art.

PORTRAIT OF PRESENT DAY MEXICO, painted nearly seven decades ago across four walls enclosing the patio of a Pacific Pallisades estate, is scheduled to go on display at the Santa Barbara Museum in December.

Siqueiros belonged to the triumvirate of 20th century Mexican muralists known as Los Tres Grandes (the Big Three)--including Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco. The mural, a gift from Siqueros to movie directory Dudley Murphy, is one of three the artist completed in Los Angeles during a six-month sojourn here in 1932. They are the only murals that Siqueiros executed in the United States.

Fleeing house arrest in Mexico, Siqueiros, an avowed Communist then in his 30s, finished PORTRAIT OF PRESENT DAY MEXICO shortly before U.S. authorities deported him. The artwork, which depicts martyred workers and a corrupt Mexican government, is arguably the most important of his Los Angeles murals and the only one to survive relatively intact.

Robert Frankel, executive director, stated the mural's donors wish to remain anonymous. However, according to the Los Agneles County tax assessor's office, the property on Amalfi Drive has belonged to Robert and Justine Bloomingdale, since 1986. (Alfred was heir to the department store fortune, a founder of Diners Club and a member of President Ronald Reagan's "kitchen cabinet.") The Blooningdales have declined to comment about the mural or their gift to the Museum.

Moving It Will Take 4 Months

The Museum must remove the mural from the estate and transport it to Santa Barbara. Each wall is 8 feet tall, the longest measuring more than 30 feet. The process, which involves a team of conservators working with construction and transportation firms, began the second week of August [2001] and is expected to take four months. The work will be moved as a unit and installed at the Museum just as it was at the estate.

Museum officials would not reveal the cost of moving the mural, nor would they disclose its current value. However, Frankel acknowledged that it is roughly in line with an appraisal conducted by Christie's in 1991, when the Bloomingdales attempted to sell the mural through the auction house.

According to Christie's public relations manager, Margaret Doyle, PORTRAIN OF PRESENT DAY MEXICO, considered to be in mint condition, was valued between $1.5 million and $2 million. . . .

Frankel declined to comment on how the Santa Barbara Museum of Art won the donation. The Museum has a nationally recognized collection of Latin American art, and in 1997 it presented "Portrait of a Decade," an exhibition of Siqueiros' work organized by the National Museum of Art in Mexico City. Frankel said he learned that the mural might be available 2 1/2 years ago."That's when we began a conservation and the donors chose to work with us," he said.

The balance of this article is available in the LATimes archives for August 22, 2001.

****************************************

PORTRAIT OF PRESENT-DAY MEXICO

Excerpt from The Mexican Muralists in the United States by Laurance P. Hurlburt, University of New Mexico Press, 1989

Siqueiros painted his final Los Angeles mural – the only one surviving today in good condition -- Portrait of Present-Day Mexico, in the semi-enclosed patio of the Santa Monica home of the film director Dudley Murphy, a close friend of S. M. Eisenstein. If, in its small size and semi-exterior environment, the mural closely resembled Rivera’s Stern mural, in contrast Siqueiros exhibited a far greater degree of political combativeness. The dimensions, some sixteen square meters, necessitated a smaller work force, composed of Siqueiros, Luis Arenal, Rueben Kadish, and Fletcher Martin, and the artists worked in traditional buon fresco.

According to Fletcher Martin, Dudley Murphy asked for an introduction to Siqueiros, saying, "Wouldn’t it be great if Siqueiros would do a fresco on the wall in my garden?" Siqueiros quickly agreed, not only for the mural opportunity, but also because living in Murphy’s residence near Malibu would keep him out of the clutches of immigration authorities (his visitor’s permit had expired). Martin recalls the working procedure for the mural:

Siqueiros would indicate a section for that night. I would mix the mortar and prepare the section. This would take maybe a couple of hours… Usually Siqueiros painted each section himself, but he occasionally would let me develop an unimportant part. He always contended that public murals should be done as a collective effort, but in practice he couldn’t stand to have anybody else paint parts that were of any importance to the composition.

He usually painted between midnight and three or four in the morning. There was always a sense of elation and accomplishment after the night’s work.

Arthur Millier remembers Siqueiros accepting the commission, planned for two and one-half months, as payment for summer rent, and that originally the artist painted "flower girls around a fountain." On Murphy’s insistence for "stronger" subject matter, Siqueiros came up with his portrait of the administration of the current Mexican president, Plutarco Elías Calles.

While obvious in content and direct in treatment – the familiar generalized, monumental figural types appear with strong light and dark modeling contrasts – Portrait of Present-Day Mexico exudes a more somber mood than the other Los Angeles murals, recalling the gravity of the Taxco political paintings. The mural was Siqueiros’ most personal in content of the Los Angeles works. Instead of depicting the general condition of North American racial discrimination or United States economic imperialism in Latin America, Siqueiros here dealt with the more specific topic of contemporary Mexican political conditions. His bitter description of the political theme of the mural surely resulted from his experiences at the hands of the Calles regime:

It represents General Plutarco Elías Calles, dressed in a Mexican outfit and armed to the teeth, with a mask, raised upon a mountain of money. One could represent Calles as the lowest symbol of corruption… About the "Highest Chief" (thus he had been ponderously named in Mexico as he received the Mexican "throne") appear anguished women, in the state of greatest misery, and many, many corpses. Possibly one of them represents José Guadalupe Rodríguez, one of the first Communists sacrificed by the ascending oligarchy.

On the three adjoining walls of the far left area, Siqueiros delineated the cause, and result, of the "corruption" of the Calles administration. He placed Calles, with mask, moneybags, and rifle, directly opposite United States imperialism, in the person of J.P. Morgan, whose presence was intended to recall that a Morgan employee, Dwight Morrow, served as United States ambassador to Mexico during the Calles era. Between Calles and Morgan lie martyred progressives and workers, the result of illicit dealings between foreign business interests and the Calles administration. Protecting the women and child (framed by two painted columns repeating the actual patio columns and seated in front of a recessive pyramid), the living victims of Calles’s politics, an armed "Red Guard" stands at the far right position analogous to the attacking revolutionaries of Tropical America. As realistic as the rest of the mural was in its depiction of the grave state of leftist opposition to Calles, the falsely positive aspect of this figure makes little sense since at this time there existed no viable leftist resistance to Calles in Mexico.

The hard-hitting political criticism of Siqueiros’ Los Angeles work made it impossible for him to obtain another mural commission after Portrait of Present-Day Mexico, political pressure against his presence in the United States led to his deportation in November 1932. Nonetheless, the "Bloc of Mural Painters" continued to function for a period after Siqueiros’ departure. And indicator of the social conditions that brought about Siqueiros’ deportation and of general opposition to the political art he espoused was the raid on the Bloc exhibition of socially oriented portable murals in February 1933 by the Los Angeles Police "Red Squad." The police actually shot and bashed with rifle butts the figures of blacks in the paintings.

Laurence B. Hurlburt, The Mexican Muralists in the United States, 1989, Univ. of New Mexico Press. pp.213-14.

COMMENTS

Conservation, Construction, and Transportation

of Portrait of Mexico Today (1932)

Conservation

Perry Huston, Chief Conservator of the project and principal of Perry Huston Associates in Dallas, Texas, called the conservation and transportation of David Alfaro Siqueiros’ mural Portrait of Mexico Today (1932) "one of the most interesting projects in America." Two factors distinguished this project from all others: the building housing the mural was transported in its entirety, including its foundation, from its original location in the Los Angeles area to its new home outside the Santa Barbara Museum of Art; and the pioneering use of a state-of-the-art conservation material called cyclododecane.

Many murals have been moved from one point to another. Those that are part of the wall, such as true frescoes, often require moving much of the wall with the mural. All possible approaches were considered in moving the Siqueiros mural. Among these were moving the mural in sections or in one piece. The mural had been painted on the inside of five walls of a semi-enclosed garden structure. The recommendation to the Museum by the Huston conservation team was to move the mural as one piece. This approach would preserve as much of the original surroundings of the mural as possible. The Museum’s decision to move the whole structure was proven to be the correct approach for a number of reasons. Among them was the later discovery that the actual mural extended below the wall four inches onto the foundation.

Huston’s conservation team included Andrea Rothe, senior conservator for special projects at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; Scott Haskins of Fine Arts Conservation Laboratory (FACL) of Santa Barbara; and longtime Huston team members Anne Rosenthal from San Francisco, Deborah Selden of New York, and Maura Duffy and Larry Keck of Washington, D.C. Also consulting were conservator Gary McGowan from New York, three assistants from the J. Paul Getty Museum, Santa Barbara Museum of Art Facilities Manager John Coplin and his assistants Jay Ewart, Ignacio Salcedo, and Nancy Rogers. The team began by documenting the mural’s condition, including photo-documentation. Photographers were Anthony Peres of Los Angeles and Scott McClaine of Santa Barbara.

The mural had been studied for a couple of years by Museum staff. Independent conservators had been asked to recommend approaches. After the Museum accepted the approach Huston recommended, Huston’s conservation team was assembled before the mural to complete the final study and begin the conservation work. Earlier analytical studies had confirmed that Siqueiros had used a true fresco technique in painting the mural. However, he had not used the traditional materials. He had used cement as a final "plaster layer" and an oil medium rather that the traditional water-soluble medium for applying the pigmented (paint) layer. The paint layer had not become locked into the wall as with true frescoes.

The conservation team was dealing with the problems associated with fresco secco (dry fresco) rather than true fresco. The team was surprised to discover that the paint solubility varied throughout the mural. "Some passages were soluble in water, and some in naptha (a mild solvent), some in alcohol and hydrocarbons," explained Mr. Huston. "Commonly, facings using materials with solubilities different than that of the paint are applied to mural surfaces to protect them when moving. However, the traditional water or solvent materials could not be used in this case because of the varying solubility parameters of the mural."

Huston called in Gary McGowan, an expert in the use of cyclododecane, a material originally developed in Europe for industrial applications. Fine art conservators have been using it with great interest for the past few years because it turns directly from a solid to a gas, with no liquid state. It could be applied to the mural and would, over the course of several months, disappear on its own, obviating the usual need to remove such a protective coating with a solvent. The use of cyclododecane would make the varying solubilities of the paint irrelevant to the conservation process. "As far as I know, this is the first time cyclododecane has been used on a project this large," said Mr. Huston. "We seemed to have procured the available world’s supply of it for this project!"

The conservators also performed more standard conservation processes, including reattaching and consolidating several flakes of paint that had come loose from the wall to hold them in place during the move. They removed the grime layer from the surface in preparation for the application of the cyclododecane. A layer of gauze was incorporated within the heavy facing layer in order to provide additional protection to the mural.

Carpentry, Construction and Transportation

John L. Sullivan, executive project manager of Armstrong Associates, Inc. of Santa Barbara, masterminded the necessary construction and carpentry for the stabilization and movement of the mural. After several meetings with Perry Huston and structural engineer Greg Van Sande of Howard Van Sande Structural Engineers, he agreed that the best approach would be to move the mural in its entirety. "I knew it could be done," said Sullivan, "and it all worked perfectly, but I had never before moved wooden studs with a priceless fresco on them."

Van Sande came up with the idea of a steel understructure, which would in essence prevent the building from twisting, or flexing, at all. While the safety of the mural was paramount, other factors had to be taken into consideration once the decision was made to move the building in its entirety and transport it by truck up the freeway to Santa Barbara. Huston, Van Sande and Armstrong all wanted to reinforce the building as much as possible, yet the whole structure had to be 12 feet, 6 inches wide and no more than 14 feet high to fit under the bridges on the highway.

After selecting expert subcontractor for the steelwork and the actual moving, Sullivan proceeded right into the carpentry and demolition work. He and his crew had to remove the plaster ceiling and take off the whole roof structure in such a way that it could be reproduced in Santa Barbara. The crew couldn’t use hammers or nails for fear of damaging the mural; they relied exclusively on drills and screws.

After the roof was removed, the construction crew moved to the foundation. They dug around the existing foundation and determined a location 16 inches below ground level to cut off the foundation. Before cutting, they cored 10-inch holes in the foundation to accept the steel cross beams, which would form the new foundation. The crew then saw-cut the whole foundation off, using diamond-cutting saws to insure minimum vibration, inserting high density plastic shims as they made each incision. After trimming the core holes so that the steel beams would fit precisely, the crew propped the beams in and put them snugly against the concrete, while welding them from below. Once the structural steel was in place, the crew erected plywood walls for even greater stability, installed in sections so that they could be easily removed and put back in place after routine inspections of the mural’s condition were performed. Once the painting was completely protected, the roof and the brick floor were removed. Each of the bricks from the floor was carefully numbered so that each could be put back in their original location. Then the whole structure was coated with the fiberwrap, a heavy-duty fiberglass that adheres to stucco and creates a very strong shell. Now the mural was ready to be put on the truck and driven to Santa Barbara.

Ted Hollinger of the Los Angeles-based company Master House Movers took charge of the move. He and his crew brought in a 120-ton crane with 110 foot of boom and moved it as close to the mural as possible. They hooked four nylon straps to the steel armature under the mural and lifted it onto the transporter, an air–ride double drop trailer pulled by a Peterbilt truck. They drove the truck from the original site to Sunset Boulevard and the 405 freeway and then up the 101 freeway to Santa Barbara. A larger crane was needed to unload the mural in Santa Barbara, because its new location outside the Museum on Santa Barbara’s main street prevented the crew from getting as close as they could at the mural’s original site. They brought in a 300-ton hydrocrane, with the capacity of 180 boom, although they only needed to use about half of the crane’s boom capacity for the unloading. The crew made the final adjustments by hand, guiding the mural to sit exactly on its new foundation.

The final phases of the conservation took place in Santa Barbara. Any loose areas within the walls were infused by hypodermic injections with appropriate materials and old losses were filled and inpainted with reversible materials.