David Alfaro Siqueiros

Mexican, 1896-1974 (active USA)

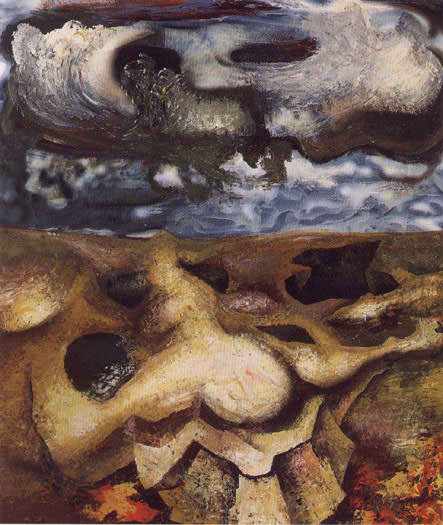

La colina de los muertos (The Hill of the Dead), 1944

Duco (pyroxilin) on board

37 1/4 x 27 in.

SBMA, Gift of Mrs. MacKinley Helm

1969.35.51

RESEARCH PAPER

Siqueiros was born in Chihuahua, Mexico in 1896 and by the tender age of 15 he had found his two great loves: art and political activism. A leader of the student strike at the Academy of San Carlos, where he was studying, he had his first experience in prison and came out exhilarated. This was the first of many run-ins with the law. During the course of his life he was arrested 7 times, was imprisoned on several occasions and spent many years in exile. During the Mexican Revolution he enlisted in the "Baby's Brigade" (Batallon Mama) of Carranza's army and at 17 was a staff officer. He traveled to Europe as a military attaché and encountered the stimulating artistic movements of the time. Upon his return he became a leader of the Syndicate [Union] of Technical Workers, Painters, and Sculptors. The group executed the social realist murals of the 1920's, commissioned by the government in support of the Revolution. Along with Rivera and Orozco, Siqueiros was one of the Tres Grandes of Mexican mural painting. Siqueiros always insisted that easel painting was subordinate to mural painting, which could be viewed by all people. For him art and politics were inseparable. In his mind, to be important art must be politically useful. Siqueiros traveled throughout the America's, frequently while in exile. He was Director of the Laboratory of Modern Techniques in Art, which opened in New York in 1936. This experimental studio school was operated by the League of Revolutionary Authors and Artists with support from the American Communist Party. Jackson Pollock was one of his students at the time and appears to have taken special note of Siqueiros' technique of dripping industrial paints. An anti-fascist, Siqueiros spent 1937-38 fighting alongside the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War. Siqueiros was to be active in leftist politics throughout his life. With the great Stalin-Trotsky schism that divided the Communist world, Siqueiros was a Communist of the Stalinist strain. So devotedly, that he was involved in an unsuccessful attempt on the lives of Trotsky and his family, who were ultimately murdered in Mexico City. Siqueiros became virtually as famous (or infamous) for this act of political intrigue as he was for his art. He died in his adopted city of Cuernavaca, Mexico in 1974.

MATERIALS AND TECHNIQUE

Siqueiros was a great innovator and strongly advocated the use of industrial materials and unconventional media in works of art. He was of the view that both an artist's subject matter and materials should be "modern". A widely told story has Siqueiros entering a paint store while in exile in Montevideo, Uruguay. The only paint available was a new industrial paint from the United States, made by DuPont, so he bought several large cans and began to experiment. Duco, or pyroxylin, was a fast-drying automobile body topcoat, which was extremely durable. He was ecstatic with the expressive potential that pyroxylin offered and soon acquired the nickname "El Duco", for his extensive use of the product. Siqueiros placed great emphasis on innovative process, as well as innovative materials. He embraced new tools developed for commercial and industrial painters, particularly the spray gun. He also used pyroxylin applied with a brush or using a controlled "dripping" technique. If the colors of the rapidly setting paint were encouraged to flow together momentarily it produced dynamic, and often surprising, shapes and forms. He referred to such a practice as a "controlled accident".

"It's a matter of using happenstance in painting, or, in other words, of using a special method of absorption of two or more superimposed colors, which blend with one another and produce the most fantastic and wondrous forms the human mind can imagine; something that resembles nothing so much as the geological formation of the earth, the polychrome and polyform streaks of mountains....In these absorptions there are the most perfect forms you can imagine. Shells of an infinite number of forms shaped with incredible perfection, forms of fish and of monsters that no one could create directly by using the traditional media of painting."

THE PAINTING

Siqueiros painted The Hill of the Dead Man in 1944, having recently returned to Mexico after several years in exile, the result of his suspected role in the first attempt on the life of Leon Trotsky. He spent the first half of the year living in self-confinement in Mexico City, attempting to avoid possible attacks from his enemies. His subject in the painting was the tragedy of war, a topic upon which he had already touched many times. Siqueiros had been dealing with themes of anti-war and anti-fascism in both easel paintings and murals since the late 30's, and he continued to take up these subjects as the war wound to a close. Other examples of similar subject matter include Echo of a Scream (1937), Museum of Modern Art, New York, Portrait of the Bourgeoisie (1939) Electrical Workers Union, Mexico City, New Democracy (1944-45) Institute of Fine Arts, Mexico City and Explosion in the City (1945) Museo del Arte Carrillo Gil, Mexico City.

The painting depicts a parched, lifeless landscape in the aftermath of war or some other great cataclysm. A smoke-filled sky is dominated by ominous clouds. They appear menacing, as if harbingers of impending doom. The sky itself seems to have been executed with an airbrush, one of Siqueiros' favorite tools. The colors swirl together, creating fantastic shapes. A barren, craggy hill or mesa lies in the foreground, edged by fires that continue to burn or perhaps blood that has been spilled. The black gouges in the earth are reminiscent of craters left by bombs. The work's abstract vocabulary invites endless speculation. Some see the eyes of a distorted skull in the clouds, or a pair of galloping horses. The foreground appears to some to contain a lifeless body or even a hideous face with a bulbous nose.

In The Hill of the Dead Man, Siqueiros creates a rich surface texture through a build up of layers of paint. This expressive handling gives the work a three dimensional, almost sculptural quality with rich textural effects. Heavy and dense, the landscape exhibits certain corporeality. Many of the shapes and forms appear to be organic. The landscape has great force and the masses give it an almost excessive weight. Siqueiros is as creative with optics as he is with textures. He manipulates the perspective in a powerful way. A foreshortening of the picture plane pushes the desolate landscape toward the viewer, creating an increased sense of anxiety or tension. It is as though the landscape is being thrust into the viewer’s space. The scene is something that cannot be avoided or viewed from afar.

Also intriguing is the repeating motif of a coiled serpent which adorns the painting's frame. There does not seem to be any information as to how the painting came to be with this frame. Perhaps it is a reference to Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent deity shared by many Mesoamerican cultures. In the Old Testament the serpent came to embody evil, as it was he who brought Eve forbidden knowledge or sin. In some cultures the snake is a symbol of renewal and regeneration, as it is able to shed its skin and begin fresh and new. The coiled snake has been considered a protector, sheltering the meditating Buddha from a fierce storm, for example, or watching over the Egyptian pharaohs.

It is interesting to note that The Hill of the Dead Man came into the collection of the SBMA as a gift from Mrs. MacKinley Helm, whose husband was a famous American art critic and a renowned collector of Mexican art. Having lived for many years in Mexico, Helm was a personal friend to many of the Mexican artists of the period. His book, Modern Mexican Painters is a must read for anyone interested in the modern Mexican movement, particularly during the 1920's and 30's. In it he discusses over 40 Mexican painters with whom he was acquainted, including Siqueiros.

Prepared for the SBMA Docent Council by Laura Creasey 2006

Bibliography

Helm, MacKinley. Modern Mexican Painters. Dover Books on Art, New York, 1941.

Micheli, Mario di. Siqueiros. Harry Abrams Inc. Publishers, New York, 1968.

National Gallery of Canada Exhibition, "Mexican Modern Art 1900-1950", February 25 2000 - May 17 2000.

Paz, Octavio. Essays on Mexican Art. Harcourt Brace and Co., New York, 1987.

Rochfort, Desmond. Mexican Muralists. Chronicle Books, San Francisco, 1993.

Stein, Philip. Siqueiros: His Life and Works. International Publishers, New York, 1994.

White, Anthony. Siqueiros: A Biography. Floricanto Press, Encino, CA, 1994.

Quote

[1] Paz, Octavio. Harcourt Brace and Co., page 158.

[2] Paz, Octavio. Harcourt Brace and Co., page 158.

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

In the mid-1930s, David Alfaro Siqueiros underwent a reevaluation of his methods, if not his aims for art. Seeking to find a revolutionary technique for a revolutionary art, he founded the Siqueiros Experimental Workshop in New York in 1936. A member of the workshop later recalled how they began using commercial automotive paint, “We poured it, dripped it, splattered it, and hurled it at the picture surface.” The artist’s radical experiments proved influential for Abstract Expressionist artist Jackson Pollock, in particular, who was a member of the Workshop.

Upon his return to Mexico in 1944, the year he painted The Hill of the Dead, Siqueiros continued his search for technical innovations in the portrayal of the horrors of war. To depict a violent storm swirling over a parched, tumultuous landscape, he used Duco (pyroxilin), an automotive lacquer produced by DuPont that he began working with in 1933. The medium allowed for a variety of surface textures, which, combined with dramatic angles and distorted views, evoke an ominous turbulence.

- SBMA title card, 2013

In the mid-1930s David Alfaro Siqueiros underwent a reevaluation of his methods, if not his aims for art. Seeking to find a new pictorial means that would be “modern” yet maintain art’s social and political function, he founded the Experimental Workshop in New York. On his return to Mexico in 1944, the year he painted El Cerro del muerto, Siqueiros continued his search for technical innovations in this portrayal of the horror of war.

In depicting a violent, stormy landscape, he used Duco (pyroxilin), an industrial product he had discovered in 1933. This new medium allowed for a variety of surface textures which, combined with dramatic angles and distorted, close-up views, suggest dynamic movement and contribute to the painting’s ominous turbulence. The expressive paint handling accentuates the abstracted organic shapes and represents a distinct phase in Siqueiros’s work in which he develops a symbolic abstraction in order to convey his personal reaction to violence as well as his long-standing commitment to humanist concerns and revolutionary change.

- SBMA Wall Text, 2000