David Alfaro Siqueiros

Mexican, 1896-1974 (active USA)

Dos Mujeres Indias (Two Indian Women), 1930

oil on canvas

28 x 22 in.

SBMA, Gift of Charles Grayson

1971.55.1

RESEARCH PAPER

It would be impossible to understand Siqueiros as an artist, a writer, or a social activist without a quick glimpse at the political and socio-economic realities of the Mexico of his time.

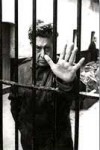

David Alfaro Siqueiros, represented here in an incredibly dynamic self-portrait, was born in 1896 from a traditional middle-class family. His formative years were spent in the political climate of the last few years of the Diaz presidency and during Mexico’s Revolutionary Period (1910 to 1934).

The socio-economic realities of Mexico were grim. Mexico’s land was still owned by a few very wealthy families while the almost illiterate masses, peons as well as Indians, lived in oppression and abject poverty. The Indians were also subject to persecution and discrimination. Foreign corporations controlled the natural resources of the country, such as petroleum and minerals, with no financial benefit trickling down to the very poor.

The long Diaz presidency (1877-1911) was marked by an almost total lack of social progress. Diaz’s main goal was to keep the status quo as much as possible. The greatly needed agrarian reforms were often discussed without much implementation. This political inertia increased social discontent and culminated in armed rebellion in 1910. Diaz was deposed the following year.

The years between 1911 and 1934 witnessed several revolutionary governments that failed to address the country’s great social problems in any meaningful way. The problems were discussed at length, but little action was taken.

PORTRAIT OF PRESENT DAY MEXICO

Aware of the terrible social injustices, Siqueiros became deeply involved in social issues and in labor struggles from an early age. A passionate communist, he was often jailed or detained under house arrest and from time to time he was also ordered to leave the country because of his political activities. So, he visited the Soviet Union in 1928, Los Angeles in 1932, participated in the Spanish Civil War from 1937 to 1938 and visited Central and South America on several occasions.

Unlike his other two great contemporaries, Rivera and Orozco, Siqueiros was not very well known as a painter during those early years. As MacKinley Helm writes in his book, Mexican painters, "..Siqueiros spent all of his time writing and talking about what he meant to do in Mexico. Meanwhile his contemporaries went to work making murals…"

During the period 1920-1940, most of the Mexican painters’ work reflected, to a degree or other, the social struggles of the time. Of the three "grandes" (Rivera, Orozco, Siqueiros), Siqueiros was by far the one who most felt the dialectics between social realities and art. He was the one who theorized the concept of Mexican social realism, the hallmark of the mural movement.

A member of the Communist party and political activist, Siqueiros defined himself as the only faithful exponent of revolutionary art for the masses. His aim was to use his dynamic revolutionary themes to inspire the masses towards the struggle against capitalistic oppression. His wall paintings are bold in composition, striking in color, a free mixture of realism and fantasy, and an expression of raw emotional power. In those murals one can always find a clear dynamic urge to struggle, expressed with sheer energy. All of these qualities make Siqueiros’ wall art very accessible to the masses.

In the painting of his murals, Siqueiros often used new techniques such as air guns, new materials such as synthetic pigments and incorporated photography in his artistic productions.

By contrast, he considered easel art quite trivial. He wrote in 1932: "We repudiate the so-called easel painting and every kind of art favored by ultra-intellectual circles, because it is aristocratic, and we praise monumental art in all of its forms because it is public property."

In spite of this statement, Siqueiros did paint several small paintings during these years. Being in and out of jail or under house arrest restricted his artistic production to smaller, more manageable sizes that could also be sold for much-needed income. However, I have found several references that Siqueiros considered his small paintings almost like pictorial drafts for larger murals. That would explain their monumental and sculptural qualities.

DOS MUJERES INDIAS

Dos Mujeres Indias, one of the paintings of female figures he produced during these years, was painted in 1930 during one of the most active political periods of Siqueiros’ life. It depicts two Indian women waiting at a train station. The figures are starkly simple, sculptural and quite anonymous. There is a somber quality to this painting in spite of the blue garb of the women and the bright red of the columnar structures defining the positive space. One can feel a deep sense of sorrow and helplessness in the women’s faceless, anonymous and humble figures. Siqueiros is telling us that they, too, are the victims of social and political oppression and exploitation. Even more tragic for them, society forbids them to actively participate in any struggle. They can only wait and endure.

By eliminating all anatomical details, Siqueiros has universalized this image and given it a sense of timeless monumentality.

Ever the innovator, Siqueiros used oil paint mixed with copal, a tree resin, in the painting of the Two Indian Women.

In closing, I would like to refer again to Mr. Helm’s book, Mexican Painters, for a practical explanation of the darkness of some of the paintings of these early years. Due to extreme poverty, Mr. Helm writes, Siqueiros used to mix his own paints. He was not very skilled in that endeavor and that resulted in paints of inferior quality which easily oxidized thus darkening the whole effect of the painting.

In conclusion, I would like to quote Sergei Eisenstein, the great Russian film director and friend of Siqueiros. He stated, "a really great artist has, above all, a great social consciousness and a great ideological conviction." Of course, this could have been a reference to himself; however, it perfectly fits the life and work of David Alfaro Siqueiros.

Prepared for the SBMA Docent Council by Gabriella Schooley