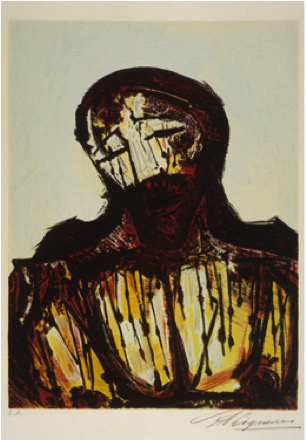

David Alfaro Siqueiros

Mexican, 1896-1974

Christ, 1968

photolithograph

21 1⁄4 x 15 1⁄2 in.

SBMA, Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Robert J. Emmons

1997.12

Siqueiros in self-portrat, 1961

"While Rivera was an incredible illustrator, in Siqueiros you see modernism in every sense of the word — the brush stroke and use of painterly vocabulary that was coming out at the time." Siqueiros served as a soldier, diplomat, union organizer, and L.E.A.R. activist. "His color lithograph ‘Christ,’ exemplifies the modernism of his work," according to Moreno. "This is very typical of the Christ figures in Puebla, Mexico, which were known for showing the bloody, Good Friday, crucified, suffering Christ with skin hanging off the ribs. It has a connection with the violence of the pre-Columbian gods who wanted sacrifice — people skinned alive and their hearts taken out — versus the U.S., where the Christ of Easter is risen and triumphant."

COMMENTS

David Alfaro Siqueiros is one of Mexico's most important artists. Born in Chihuahua, Mexico, the artist attended the Open Air Art School in Santa Anita, Mexico. In 1914, he enlisted in the army, fighting in the Mexican Revolution. He painted his first mural in 1923, the beginning of a long career that would make him famous throughout Mexico and the United States. The Santa Barbara Museum of Art recently celebrated the installation of a Siqueiros mural that had been moved from a private home in Pacific Palisades. Another important mural painted in downtown Los Angeles is now being restored by the Getty Museum.

David Alfaro Siqueiros is receiving more recognition now than ever before in his history. Museums in Los Angeles, as well as in other major cities in the United States in recognition of the Centennial of the Mexican Revolution and the Bi-Centennial of Independence are mounting major exhibitions. Museums have chosen to highlight the art of this great Mexican Master artist. He is known as one the three Mexican Master artists, along with Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco.

Siqueiros was a social realist artist, always concerned with the lot of the Mexican common people and their struggles. Throughout mid and later life, his politics became highly intertwined with his art, and he spent time in prisons, drawing much attention for his strong political views. In 1919 Siqueiros traveled to Europe for the first time, meeting Rivera in Paris and traveling with him to Italy to view Renaissance frescoes. He participated in the Venice Biennale in the early 1950's with Rivera, Orozco and Rufino Tamayo. In the 1960's the artist became an active lithographer, and it is during that period that a number of editions were published, making the work of this great master more accessible and affordable.

“The Mexican Suite” was originally complete with ten original color lithographs, signed. [Paris: Mourlot, 1968]. Very large folio (20-1/2 by 27 inches), 10 loose lithographs in original salmon cloth clamshell box. A large folio depicting social conditions during the Mexican Revolution, each impression numbered and signed by Siqueiros in pencil. The bold and vividly-colored lithographs of contorted and emotional figures, reflecting the social and polemical issues of his time. His use of montage, along with photographs and the air-brush, created the illusion of movement, which has become a “signature aesthetic in his work… [and] a characteristic which in his best known works places him among the masters of the line in this century” (Margarita Nieto).

Siqueiros focused on dynamic revolutionary themes, rooted in the Spanish Civil War and the Mexican Revolution, in which he personally participated. The 30-year period of 1920-50 has been called the Mexican Mural Renaissance, and he was a key figure in an attempt to establish an indigenous art that would be at the same time universal.

Tolstoy said the purpose of art is to transmit man’s "highest and best" feelings. Diego Rivera said, "All art is propaganda."

It’s not unusual that Tolstoy and Diego Rivera, coming from different cultures, held seemingly dissimilar viewpoints on the purpose of art, and that, depending upon the perceptions of the viewer, examples of both interpretations might be found in the museum’s permanent collection. Still another visitor might conclude that the two perceptions are not at odds, but one and the same — that the yearning for social justice may be one of man’s "highest and best" feelings.

Some of the most well-known examples of what some might consider "Art as propaganda" came later, born of the economic and political programs of President Porferio Diaz, and other latter-19th century Mexican presidents, when Indians and farm workers were exploited by large companies, and when, in 1910 on the eve of the Mexican Revolution, only a few hundred families owned most of the land in Mexico.

"During the Mexican Revolution from 1910 to 1921, all the people of Mexico left their homes and towns and traveled across the country to fight." says Mareno. When they returned home, after seeing other towns and villages, an education of the masses had taken place that solidified Mexican culture. That later became known as Mexicanidad.

"After the revolution, two artistic movements, the printmakers and the muralists, took it as their mission to celebrate the culture and history of Mexico and educate the people."

Printmaking was commonly used in Mexico for social protest. Prints could be easily mass-produced for wide distribution.

Meanwhile, the most well known of the muralist movement artists were Jose Clemente Orozco (1883-1975), Diego Rivera (l886-1957), and David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896-1974), who painted murals of the revolution on walls of public buildings.

Jean Charlot, who was born in 1898 in Paris and moved to Mexico in 1921, actually created the first true fresco murals in Mexico in 1922. Orozco, Siqueiros, and Rivera followed his lead. Charlot, a prolific artist and writer, promoted Mexican art in the U. S. and Mexico, including the engravings of Jose Guadalupe Posada.

"Leopoldo Mendez was one of the premier printmakers to come out of the movement," says Moreno. The SBMA’s prints (linocuts) — exemplify his mastery and demonstrate the power of graphic arts. A member of the League of Revolutionary Artists and Writers (L.E.A.R.) and contributor to its periodical "El Machete," he founded The Workshop of Popular Printing. Mendez attacked the treatment of the rural poor.

Diego Rivera, the most publicized Mexican painter of his era, was born in Guanajuato, studied in Europe and returned to Mexico in 1921 to become a leader in the muralist movement, redefining the Mexican heritage and breaking free from the constraints of classical European art. "These were," says Moreno. "He was famous for drawing everyday people. Drawings from his sketchbooks were used in the murals. People knew what they were looking at and could appreciate their own culture, because they could see it celebrated in art."

Bob McCray, The Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum

heritagegallery.com