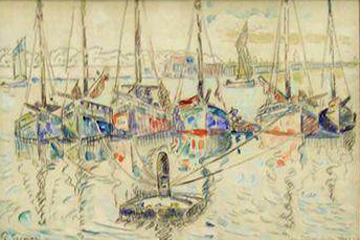

Paul Signac

French, 1863-1935

Croix de Vie, 1920

watercolor and pencil on paper

11 x 16 3/8 in.

SBMA, Gift of Dwight and Winifred Vedder

2006.54.13

Undated photo of Paul Signac

"If, therefore, you’ve already considered that Signac and the others who are doing pointillism often make very beautiful things with it, instead of running those things down, one should respect them and speak of them sympathetically, especially when there’s a falling out. Otherwise, one becomes a narrow sectarian oneself, and the equivalent of those who think nothing of others and believe themselves to be the only righteous ones." - Letter to Emile Bernard, December 1887

In the words of Paul Signac, "Oil painting is a stern struggle; watercolor is only a playful game" (qtd. Francoise Cachin 123).

RESEARCH PAPER

Paul Signac was born into a well-to-do family in Paris in 1863. His father and grandfather, who had been a sea captain, owned two elegant saddlers shops in the centre of Paris. This family business made it possible for Signac to be financially independent. In 1880, when Signac was only 17 his father died and the family moved to Asnieres, on the outskirts of Paris. It was also in 1880 that Signac bought his first painting by Paul Cezanne which would become the beginning of his lifelong collection.

In 1882 Signac had his first studio and started to paint; he was a self- taught artist with no academic training. His grandfather's seafaring influence and Signac's own affinity to sailing can be seen throughout his career. His early paintings were influenced by Monet; Signac would work in oil and in watercolour on paper. He helped set up the 1884 Salon des Independants and later became its president in 1908. His contemporaries included Seurat, Pissarro, Guillaumin and Van Gogh whom he visited in 1889 when Van Gogh was in a mental institute in Arles. Signac was also influenced by Seurat's style of Pointillism, also known as Divisionism. In 1886 he exhibited in the eighth and last Impressionist exhibition alongside Pissarro, Seurat and their friends.

As well as a painter, Signac was also a traveler. In 1890 he visited Italy and summered in the south of France, sailing in his boat L'Olympia. In 1891 Seurat died and the following year Signac met Berthe Robles, a distant cousin of Pissarro, in St Tropez. They married and bought a house there, thus 'discovering' St Tropez. Signac began experimenting with watercolour as his medium.

In 1894 he renounced plein air painting and worked primarily in his studio, elaborating drawings and watercolours begun outside into paintings composed of small mosaic like squares of colour quite different from the variegated dots of pointillism/divisionism.

During the next 10 years he continued to travel, as well as to write. His books include "From Eugene Delacroix to Neo-Impressionism", and "Jongkind", a book about the Dutch painter whom he admired. In 1902 he had his first solo exhibition of watercolours. Watercolours became an important part of Signac's work, allowing more freedom than the rigidity of oil. In the summer of 1904 Matisse joined him in St Tropez where it is believed that Signac influenced the young Matisse in the use of primary and secondary colours. His sojourn in St Tropez was followed by travel to Constantinople, Venice and London. During his presidency of the Salon des Independants, Signac encouraged young artists, including Henri Matisse and Andre Derain, and authorized the exhibition of the none-too-popular works of Fauvism and Cubism. In 1910 the Seine flooded, prompting him to commence his first series of watercolours, Les Ponts de Paris (The Bridges of Paris).

With World War I (1914 -1918) approaching, he moved to Antibes in 1913 with his new partner, the painter Jeanne Selmersheim-Desgrange, and their daughter, Ginette. He was very unsettled by world events; the Russian Revolution was also at this time, 1917-1920, and he did very little painting during this period.

In 1919 he returned to Paris, now preferring drawing and watercolour to oil. He continued to move around, renting a house in St Paul de Vence on the French Riviera in 1921 and again in 1922 in Vivier on the Rhone. Later, his favourite holiday location was Lezardrieux in Brittany. In 1928 he met Gaston Levy who collected Signac's works and began a catalogue of his work. Signac was invited to join M. Levy and his family and friends in La Baule, Brittany. At this time Signac suggested that Levy commission a series of watercolours on the harbours/ports of France (Les Ports de France). The idea was to paint two watercolours of each chosen French harbour, 100 in total. Levy agreed. This collection is rather like a diary in that we can follow Signac around the French ports, as each watercolour was dated. He set out in 1929 with his boat to tour the French coastline; the series was completed in 1932.

On the completion of this commission, he purchased a house in Barfleur on the coast of Normandy. He spent the rest of his days overlooking the harbour and lighthouse, watching the comings and goings of the boats. He enjoyed the unsophisticated local fishermen as well as the wild Normandy coastline. Having always been fond of the sea and boats, his natural attire was a fisherman's polo neck sweater and a sailor cap; his jacket pocket would have been large enough to hold a small sketch pad and a paint box. He remained an avid sailor and explorer until his death in 1935 at the age of 72.

Croix de Vie, 1920 - The Painting

This vibrant pencil and watercolour drawing was made in the Brittany harbour of Croix de Vie in 1920. It is a view of the harbour, possibly from Signac's own sailing boat, as the scene appears to be mid-channel with the fishing boats moored to a floating buoy. This is the type of open air sketch in which Signac took such delight, enjoying the ability to capture the moment and movement of the boats on the water. He, indeed, had a whimsical approach to his subject, making use of contrasting pure and opposing colours for vibrancy. His compositions were simple, yet factual. One might see some of the same landmarks today. Note the reflections on the water; it would appear to be a calm day, very little wind to ruffle the surface of the water. The sails of the two fishing boats in the background leaving the harbour confirm the lack of wind as their sails are not full, the boats are moving slowly. We can see that the sky has light cloud and is overcast; hence there are no bright reflections of the sun on the water. The town of Croix de Vie can be seen in the background.

As this was painted in 1920 it is not part of the Ports de France series commissioned by Gaston Levy. However, Signac did include Croix de Vie in this series with another scene of the harbour painted in 1929. He would often paint the same harbour several times but from a different angle and with a different subject matter. Signac's works are full of life and bright colour, perhaps reflecting his own personality into his paintings.

Prepared for the SBMA Docent Council by Ann Hammond, March 2007

Bibliography

Paul Signac - A Collection of Watercolors and Drawings by Marina Ferretti Bocquillion and Charles Cachin (SBMA Library)

Paul Signac by Charles Cachin (SBMA Library)

SBMA Docent Files

Tate Online Collections Glossary / Salon

Tate Online Collections Glossary / Neo-Impressionism

www.artchive.com/artchive/S/signac.html

www.renoirinc.com/biography/artists/signac.htm

blogs.princeton.edu - A Brief Biography of Paul Signac

POSTSCRIPT

It was Camille Pissarro who in 1888 had first suggested the medium to Signac in a letter: "I recommend watercolor to you; it is delicate and very practical. In a few minutes you can take notes you could get in no other way: the fluidity of a sky, certain transparencies, a whole lot of little pieces of information that hours of work would never give you" (qtd. Francoise Cachin 77).

"His nature predisposed him less to inner torments than to the masterful development of his own gifts, which were not imagination or introspection, but observation and a taste for action and life" (Francoise Cachin 9). His taste for "action and life" manifests itself mostly clearly in his love of the outdoors since he remained an avid sailor and explorer until his death at the ripe old age of seventy-two.

Signac - Herblay - The Riverbank (Op. 204), 1889

COMMENTS

To discover what influences affected Van Gogh in Paris, one should recall the artistic developments there between 1886 and 1888. In June, 1886, the last Impressionist exhibition closed. Monet, Renoir, and Sisley, prime movers in Impressionism, had refused to exhibit because Pissarro had insisted that Seurat and Signac be included. Nevertheless, while Impressionism as a movement was disintegrating, its members were still very productive and the colorful vibrancy of their brush strokes, suggesting the shimmer of sunlight, must have revolutionized Van Gogh's conception of coloring.

More immediately, however, he was affected by the advice of the Neo-Impressionist Signac, who under Seurat’s influence had won over Pissarro to the pointillist technique of using tiny spots of color in a really systematic way. Van Gogh, always fascinated by color theories, was already familiar with Delacroix’s ideas, which he had reported faithfully to Theo in an earlier letter. But Delacroix had not liberated him from using dark colors, because as Signac pointed out in his book, From Delacroix to Neo-Impressionism, Delacroix had combined pure prismatic hues with earth colors so that his pictures lacked real brilliance. Although Delacroix had understood that juxtaposed complementary colors — red-green, yellow-violet, blue-orange — augment each other’s intensity, he had diluted their effectiveness with dark shades. In contrast, the darkest tones Signac used were the pure colors. Further, Delacroix had mixed his colors on his palette instead of relying on "optical mixture,” a new and highly recommended technique behind which lay the researches of Eugene Chevreul of the Gobelin tapestry factory, as well as other scientists who had also analyzed color vision. Optical mixture depends upon the ability of the eye to merge the light rays from very small dots of color so that from a distance one color of light would appear added to another to give the effect of a new, more brilliant hue. (One can see this effect in most color reproductions; if they are examined under a powerful magnifying glass, separate dots of color appear which are not evident to the naked eye.)

Signac charged that the Impressionists had failed to achieve real brightness because they had not used touches of paint small enough to permit optical mixture, and also because, with their intuitive procedures, they had not methodically juxtaposed complementary hues to gain maximum color intensity. Curiously enough, however, the Impressionists’ works appear brighter than Seurat’s or Signac’s. This may be due to several reasons: the pointillist touches of paint may be sometimes too small to register on the eye from a reasonable viewing distance, and hence are lost, while the broader touches of the Impressionists are really more effective; or again, the tiny touches of paint may actually merge their colors and merely give a dull gray effect of light. Finally, the more generous tonal contrasts in Impressionist pictures may suggest brighter effects of light than Neo-Impressionism could command.

Whatever the reasons, one can see that Van Gogh did not take pointillism seriously for very long. Although painting with Signac, he rarely submitted to the tedious discipline of painting in small dots; in fact, he soon lengthened his touches of paint until they assumed a very distinctive rhythmical calligraphy, which has nothing to do with either Impressionism or Neo-Impressionism. He was really not interested in pinning down vivid sensations of light as such, so that his brushwork soon served instead to increase the feeling of life in the surfaces he painted, and to reinforce his draftsmanship.

- Grose Evans, Van Gogh, The National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., 1968, 20-22