Walter Richard Sickert

British, 1860-1942 (active England and France)

View of Dieppe, c. 1899

oil on board

6 1/8 x 9 3/4 in.

SBMA, Gift of Mary and Will Richeson, Jr.

1974.35.1

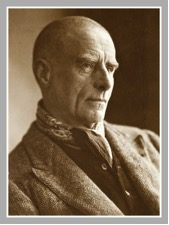

Walter Sickert, photograph by George Charles Beresford, 1911

"To justify our likes and dislikes, we generally say that the work we dislike is not serious." - Walter Richard Sickert

RESEARCH PAPER

This small oil on wood panel painting shows a simple landscape with the town of Dieppe, where his wife had grown up, in the background. Like most of Sickert’s paintings, this one is not dated and since he spent so much of his time in Dieppe off and on during his life, it is not easy to assign a date to the work. However, likely it is from one of his early visits there when he concentrated on landscapes and also from the time when he was still more under the influence of Whistler, since he copied Whistler’s proclivity to paint oil on wood panel. This was also a time when he painted more loosely and quickly with the paint more thinly applied, as seen here. In some areas the paint has been washed on in such a thinned down manner that it is almost possible to see the wood grain through the paint. In the foreground is a large green grassy area with a great strip of road running horizontally across the picture plane. The colors are lighter, but still retain a gray, slightly muddy quality, perhaps from his practice at that time of painting a grey ground on his canvas which gave a somber glow to his work. The buildings in the background almost impart an industrial smoky quality, which was not actually the character of the town.

To understand the work of Walter Richard Sickert one must gain insight into his life, times, and background. For, to a much greater extent than for many artists, Sickert was one whose painting was almost totally entwined with the events of his own long and full life. He has been called the most important English painter since Turner and there is no question that he remained the pre-eminent English artist throughout his working life. In spite of all these accolades from the artistic community, the general public has not granted Sickert the same popularity, perhaps because of the difficulty in appreciating some of the characteristics of much of his painting, such as his often dark and muddy palette, his lack of detail in execution, and his continual experimentation with new styles and techniques.

Although classified as an English artist, Sickert’s actual background and heritage is more European. He was born in Munich in 1860, the eldest son of a Danish artist who had become a German citizen through the annexation of Schleswig-Holstein by Prussia in 1868. Sickert’s mother was the illegitimate daughter of an eminent English astronomer and an Irish stage entertainer. She had been brought up in Dieppe and later in Germany. It was not until after the Prussian annexation that Oswald Sickert moved his family to England, mainly so that his sons would escape conscription into the German army. During his own lifetime, Sickert spent much time in Dieppe which he painted frequently, and in Venice, and these escapes abroad further gave a more European and less English character to his work. This potpourri of national heritage plus his home environment in a large, gregarious, active family of six children where art, music, literature and the stage always played an important role, created the atmosphere in which his genius could flourish.

Sickert’s first career was as an actor from 1877 to 1881, an interest which never totally left him, as is evidenced by the immense and outstanding collection of his works which deal with the theater and specifically with scenes from the music halls of England. After a short sojourn at the Slade School of Art, he joined Whistler’s studio as his student, etching assistant, and helper. It was on an errand to Paris in 1883 that Sickert first me Degas who proved to be the second great artistic influence in his life. By 1885m when he again met Degas in Dieppe, he was beginning to turn away from some of the teachings of Whistler, and incorporate the more studied and less spontaneous methods of Degas. It was at this time also that Sickert married his first wife, Ellen Cobden, twelve years his senior and the wealthy daughter of a well known politician. It was during this period that he spent much time in Dieppe during the summers. He alternated paintings with Dieppe as the subject and with drawings of the English music halls. In 1898, after his divorce from his first wife, he moved to Dieppe and remained there until 1905, when he returned to London, a time interrupted only by a year spent in Venice from 1903 to 1904.

After his return to England, Sickert plunged into a period of work known as his Camden Town Period from the area of London in which he lived; it was a time of rediscovery for him of his previous interest in the music halls, of a new dimension in both subject matter and exploration of different techniques. This period also coincided with his second marriage to Christine Angus and World War I, which forced the Sickerts to remain in England and not visit their beloved Dieppe until they returned there permanently in 1919. Christine died there in 1920. The paintings and drawing of this period convey the sadness and loneliness that Sickert was struggling with in his life. In 1925 he returned to London, engaged himself busily both in teaching and writing again, in addition to painting. In 1926 he married his third wife, Therese Lessore, a longtime friend and fellow artist. Walter Sickert died at the age of 82 in 1942. His body of work is immense; his subject matter is extremely varied, from wonderful landscapes and architectural scenes, to portraits and narratives of the poignancies of life, scenes of the theater, and drawing, etchings, and paintings.

From the paintings by Sickert presently in the collection of the Santa Barbara Museum of Art it is not possible to grasp the tremendous versatility and range of techniques of Walter Sickert. He is an artist who defies classification into any one school or style. Instead he was able to experiment and explore on his own, grasping those techniques of other artist that suited his temperament and talents, and applying his talents to a broad spectrum of work.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Nyna Mahan, April 1986

Bibliography

Arts Council of Great Britain. “Leeds” Painting: 20th Century British Art from Leeds City Art Gallery”, 1980

Arts Council of Great Britain. “19th and 20th Century Drawings and Painting from the Courtauld Collection”, 1977

Arts Council of Great Britain. “Paintings, Drawings and Prints of Walter Richard Sickert 1860-1942”, 1977-78

Walter Richard Sickert with his Head Shaved c.1920 Tate Archive TGA 8120/2/3

COMMENTS

Unlike the majority of the Camden Town Group, Walter Richard Sickert was recognized during his own lifetime as an important artist, and in the years since his death has increasingly gained a reputation as one of the most influential figures in twentieth-century British art. He was universally acknowledged throughout his life as a colorful, charming and fascinating character, a catalyst for progress and modernity, yet someone who remained independent of groups, cliques and categories. As a younger man he was widely reported to be an entertaining and skilled raconteur, popular within cultural and social circles and friendly with numerous famous personalities of the era. In his old age he cultivated his many eccentric habits and courted a level of celebrity, frequently appearing in the newspapers for having changed his appearance, his name, or for his latest controversial painting stunt. His art, like his personality, is multifaceted, complex and compelling.

Sickert was a cosmopolitan figure. The eldest of six children, he was born in Munich on 31 May 1860 to a Danish father (with German nationality) and an Anglo-Irish mother. His early years were spent in Germany, but in 1868 the family moved to England. London remained his principal home for the rest of his life, although he also lived for periods in France and Italy. He spoke fluent English, German and French, and had a good command of Italian. His father, Oswald Adalbert Sickert, was a painter and woodcut illustrator for a comic paper, the Fliegende Blätter, and although his young son received no early formal training, art and culture formed an integral part of his upbringing. His schooling was undertaken in a variety of establishments including the King’s College School, London.

At eighteen, Sickert was discouraged from pursuing an artistic career by his father and turned instead to his other great passion, the theatre. Under the alias ‘Mr Nemo’, he took up acting and appeared in minor roles in several touring productions. Art, however, continued to occupy him and in 1881 he signed up for a year’s ‘General Course’ at the Slade School of Fine Art. The final step towards his chosen path came in 1882 when Sickert abandoned the stage in order to become an apprentice in the studio of his great hero, James Abbot McNeill Whistler (1834–1903). The American artist advised him to leave the Slade, remarking with characteristic acerbic wit, ‘You’ve lost your money, no need to lose your time as well’.1 Sickert’s role under Whistler was largely that of a studio assistant and he learned a good deal of technical and practical knowledge about painting and printmaking. By observation, he also imbibed lessons about Whistler’s painting techniques and began to produce work himself in the style of the master. In 1883 he was entrusted by Whistler to courier his famous Portrait of the Artist’s Mother to the Paris Salon,2 a trip which led to an introduction with the other great influence in his life, Edgar Degas (1834–1917). Over the next five years he continued to learn from the example of these two great figures of modern painting and began to establish a reputation for himself as a painter of low-toned landscapes. In 1885 he married his first wife Ellen Cobden and the couple spent the summer touring Europe, culminating in a prolonged stay in Dieppe, the town that was to become a beloved fixed constant in his life. He renewed his acquaintance with Degas and made friends with many other young French writers and artists including Jacques-Emile Blanche (1861–1942).

Following Degas’s example, Sickert began to move away from Whistler’s instruction to paint from nature with a wet-in-wet technique. Instead, he established the regime he was to follow for the rest of his life of painting in the studio from drawings made on the spot. By 1887 he had fixed upon the theme which would occupy him intermittently for most of his career, the world of the British music hall, exhibiting his first painting of this subject, Le Mammoth Comique, at the Society of British Artists. A natural platform for his work at this time was the recently formed New English Art Club, which Sickert joined that year. His arrival crystallized a split within the group between the more conservative artists and those who looked to the example of French impressionism. The latter appeared as a breakaway group, the ‘London Impressionists’, in an exhibition at the Goupil Gallery in December 1889, and included, as well as Sickert, Philip Wilson Steer, Frederick Brown, Theodore Roussel, and Sickert’s brother, Bernhard.

Sickert continued to focus on the music hall as a source of inspiration, but also began to concentrate on portraits, domestic scenes from everyday life, and landscapes of Dieppe and Venice, which he visited for the first time in 1895. Following his separation and divorce from Ellen (on the grounds of his adultery) and a growing disillusionment with the New English Art Club, Sickert moved to Dieppe where he remained (with occasional sojourns in Venice) until 1906. He continued to exhibit in England, but did not return to live there until a chance meeting in Dieppe with the young artist Spencer Gore tempted him back to join the new generation of progressive artists in Britain. Back in London, Sickert established himself in rooms in Camden Town and began to hold Saturday afternoon ‘At Homes’ in his studio in Fitzroy Street. His regular core of visitors became the more formalised ‘Fitzroy Street Group’, an independent, modern exhibiting society which, in 1910, evolved into the Camden Town Group. Sickert exhibited at all three of the group’s exhibitions, although his contributions were markedly different from both the subject matter and visual appearance of the other members. The paintings which drew the most interest from the critics were those which formed the ‘Camden Town Murder’ series, a number of low-toned scenes depicting a naked woman on an iron bedstead, observed by a fully clothed man. The Camden Town Group later reconfigured into yet another permutation, the London Group, from which Sickert resigned in 1914. That same year he rejoined the NEAC where he exhibited his most famous painting, Ennui (Tate N03846).

During the First World War, Sickert was unable to take his usual summer vacation in Dieppe and began for the first time to form associations with other places, first Chagford in Devon, then Brighton and later Bath. The war years also saw a concentrated period of etching in a studio in Red Lion Square, London. After the war, Sickert promptly returned to France and settled in Envermeu with his second wife, Christine (whom he had married in 1911). In 1920 Christine died after a long illness and by 1922 Sickert once again moved back to London, this time eschewing Camden Town for nearby Islington. In 1926 he married his third wife: friend and fellow artist Thérèse Lessore (fig.3).

In the later years of his life, Sickert reinvented himself physically, professionally and artistically (fig.4). In 1927 he dropped his first name, Walter, and chose instead to be known merely as Richard Sickert. His paintings still featured a familiar range of subjects including domestic interiors, portraits, townscapes and theatrical subjects but increasingly relied on photographs, instead of drawings, as the basis for his compositions. His work gained a new level of publicity attracting both controversy and respect. Despite some considerable success and the attainment of a level of established respectability (during the 1930s he was elected to the Royal Academy and received honorary degrees from the universities of Manchester and Reading), his poor financial management brought him into difficulties. In 1934, partly as a cost-cutting exercise, he moved to St Peter’s-in-Thanet, near Broadstairs in Kent. In 1938 he moved once again to his final home in Bathampton, Somerset, where with the assistance of Thérèse and his long-term supporter Sylvia Gosse he continued painting until just before his death on 22 January 1942.

Sickert’s contribution to British cultural life was not restricted to his artistic output alone. He also exerted considerable influence as a writer and teacher and was a generally proactive, political force in artistic circles. He was a member of numerous societies and groups and played a vital role in the dissemination of new ideas and concepts from France to England. He taught intermittently throughout his life, both in established art institutions such as the Slade, the Westminster School of Art, and the Royal Academy Schools, and in his own private schools which he opened and closed with optimistic frequency. He was widely applauded as a gifted and inspirational tutor, teaching, among many, David Bomberg, Winston Churchill and Lord Methuen. His career as a writer lasted for nearly fifty years, during which time he regularly wrote for a number of publications including the Burlington Magazine, New Age, Art News and Speaker. In addition, like his former mentor Whistler, he was an inveterate letter writer to the press and bombarded the newspapers with commentary and opinions. His importance as an art critic has been somewhat overlooked, overshadowed by the pre-eminence of contemporaries such as Clive Bell and Roger Fry. Unlike his Bloomsbury colleagues, Sickert did not highly rate the work of the post-impressionists Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso and the progressive nature of his writings was therefore underestimated. The publication of his collected writings in 2000, edited by Anna Gruetzner Robins, fully revealed for the first time his extensive contribution to shaping British attitudes to art in his own lifetime.3

The first retrospective of Sickert’s work, organized during his lifetime by Lillian Browse, was held in 1941 at the National Gallery.4 In the same year, the first biography of the artist appeared, written by a friend and pupil, Robert Emmons.5 After his death Sickert remained a notable but underestimated figure. His work was well represented in the nation’s public galleries, but he was perceived as problematically independent of the major identified movements in British art. In the latter half of the twentieth century, however, his work was reassessed and his importance revalued. Artists such as Frank Auerbach and the Euston Road School acknowledged a direct link to Sickert’s figurative and domestic interiors. The scholarly work during the 1960s and 1970s of Lillian Browse and Wendy Baron established and formed the invaluable basis for all later Sickert studies.6 In 1975 Richard Morphet compared Sickert’s use of photo-based source material to the later developments in pop art,7 and an exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in 1981–2 established the contribution to British modernism of his previously ignored late paintings.8 In 1992 Wendy Baron and Richard Shone curated a major show at the Royal Academy which provided the first major overview of his entire oeuvre.9 Anna Gruetzner Robins’s 1996 publication, Walter Sickert: Drawings, enhanced his growing reputation with a survey of his work as a draughtsman,10 while in 2000 Ruth Bromberg produced a catalogue raisonné of his achievements as a printmaker.11 The nearest publication to a catalogue raisonné of paintings and drawings is Wendy Baron’s comprehensive Sickert: Paintings and Drawings published in 2006.12

The twenty-first century has seen a sustained period of Sickert research and exhibitions, crystallising his reputation as one of the most significant British artists of the early modern period. In addition, his celebrity was assured by the crime fiction writer, Patricia Cornwell, who published a book in 2002 claiming that Sickert was Jack the Ripper. Her assertions caused a schism among Sickert scholars, but were widely agreed to be improbable and unsubstantiated. The arguments she propounded in Portrait of a Killer: Jack the Ripper – Case Closed were systematically countered by Matthew Sturgis in the last chapter of his extensive biography, Walter Sickert: A Life, published in 2005.13

Nicola Moorby, Comments from Tate Research Publications, May 2006

Notes

1

Hubert Wellington, Walter Sickert 1860–1942: Sketch for a Portrait, 10 February 1961, BBC Home Service recording, LP 26656, Side 2.

2

Arrangement in Grey and Black No.1, Portrait of the Artist’s Mother 1871 (Musée d’Orsay, Paris).

3

Anna Gruetzner Robins, Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford 2000.

4

Sickert, National Gallery, London, August–December 1941. Introduction by Lord Methuen.

5

Robert Emmons, The Life and Opinions of Walter Richard Sickert, London 1941.

6

Lillian Browse, Sickert, London 1960, and Wendy Baron, Sickert, London 1973.

7

Richard Morphet, ‘The Modernity of Lake Sickert’, Studio International, vol.190, no.976, July–August 1975, pp.35–8.

8

Late Sickert: Paintings 1927 to 1942, Arts Council tour, Hayward Gallery, London, November 1981–January 1982, Sainsbury Centre for the Visual Arts, University of East Anglia, Norwich, March–April 1982, Wolverhampton Art Gallery, April–May 1982. Texts by Frank Auerbach, Richard Morphet, Helen Lessore and Denton Welsh and catalogue by Wendy Baron.

9

Wendy Baron and Richard Shone (eds.), Sickert: Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 1992.

10

Anna Gruetzner Robins, Walter Sickert: Drawings, Aldershot and Vermont 1996.

11

Ruth Bromberg, Walter Sickert Prints: A Catalogue Raisonné, New Haven and London 2000.

12

Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006.

13

Matthew Sturgis, Walter Sickert: A Life, London 2005.

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Sickert mingled freely in the artist’s colony in Dieppe, where he got to know, among others, Edgar Degas, Henri Gervex and Jacques- Emile Blanche, who described him as the Canaletto of Dieppe. Degas’s great 1885 pastel Six Friends at Dieppe - the Halévy brothers, Sickert, Blanche, Gervex and Albert Boulanger-Cavé - is in the collection of the Rhode Island School of Design.

- British Modernism Whistler to WWII, 2016