Yinka Shonibare

British, 1962- (active Nigeria)

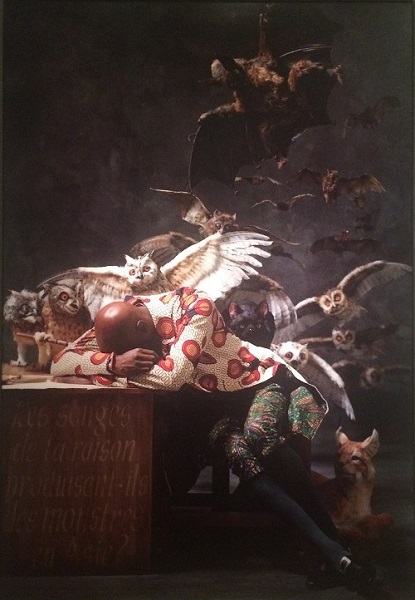

The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (Asia), 2008

chromogenic print mounted on aluminum

72 x 49 1/2 in.

SBMA, Museum Purchase, the Austin Fund in Honor of Wright S. Ludington

2009.14

Yinka Shonibare MBE. Photograph by Marcus Leith

RESEARCH PAPER

The Trojan Horse, a magnificent offering to the goddess Athena and the city of Troy, is not unlike this chromogenic photograph by Yinka Shonibare, CBE, and it is similarly impressive. It is large, rich in color and form and like the Trojan Horse, is beautifully deceptive!

To begin, light filters down from the top left corner, bathing the man, desk and three owls in light, focusing our eyes there as well as highlighting the central focus within Shonibare’s print. “Relativity is what I want to highlight and play with.” (Downey, #93) The other creatures are tinged with light but recede into the grey shadows of the background. Each aspect of the scene is representational and nothing is what it seems.

A black man rests with his head in his arms on a desk. Shonibare has clothed him in colorful Victorian style garments that are synonymous with African cultures. This Dutch wax fabric, a bright and distinctive cloth, was actually originally produced by the Dutch in the 1850s and eventually sold to West Africans, for whom it became popular and representative of their cultures. A colonial invention, Dutch wax fabric represents an “authentic” sign of being of Africa the world over and yet there is a different truth as to its origin.

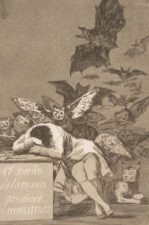

The desk, associated with learning, reason, and the cultivation of the intellect, bares a question on its side - “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters in Asia?”, is posed as a question (unlike that of Goya) and is written in French, a nod to the origins of the Age of Reason or Enlightenment (1715-1789). The whole scene in fact, is staged to resemble the original aquatint etching by Spanish artist Francisco Goya y Luciente (1797-1799), created for his series “Los Caprichos”. The pieces of both artists are saturated with references to our ways of reasoning both then and now.

The man, would seem to be asleep and perhaps his sleeping on the desk would signify a greater question: Is humanity ‘awake’ and guided by wisdom and reason or is it ‘asleep’ and ignorant in thought and behavior? In “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters in Asia”, Shonibare “re-contextualizes the question of reason (or the absence thereof)” (Madrid, EIL, Escapeintolife), referencing humanity’s awareness as a whole. What arises from this piece and his other works, are questions regarding our perceptions of authenticity, class, race and cultural identity.

We might assume that the man might be Asian given the title references Asia, but he is instead a black man. Issues of identity, authenticity, and colonization extensively inform Shonibare’s work and it’s nowhere more apparent than in this series of five chromogenic prints titled “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters in (Asia, Europe, Africa, Australia, America)”, created in 2008, in which Shonibare plays with off balancing our stereotypical assumptions by using men of five different ethnic cultures, associating each with a different continent. “Different cultures want to group together, they want to stick to their own culture, but what I do is create a kind of mongrel. In reality most people’s cultures have evolved out of this mongrelization, but people don’t acknowledge that.” (Downey, #93), not unlike his own self view as a ‘cultural hybrid.’

Owls which are featured prominently in this piece, were said to represent foolishness during the Middle Ages “because (they were) active at night and almost blind by day” and thus “became associated with stupidity”. (Rijksmuseum.nl) And yet during our contemporary time, owls have also been attributed to truth and wisdom. (Harris. Spirit Animal) They are gathered close to the man, and the two to his left peer at him with their orange eyes wide. They prod him with a brush as if to awaken him or offering a tool for his use on the papers under his arm. There is a third white owl with wings outstretched that hovers just behind them to conceivably also help waken the man. Above the sleeping scene, a dark and sinister bat-like creature (symbol of ignorance and stupidity) descends

from the top of the photograph leading a host of other flying bats and owls. It matters not whether these creatures represent wisdom or foolishness, for in the end, Shonibare’s desire is to present a picture of mankind in need of being ‘awakened’ into wisdom from his sleep of ignorance and lack of awareness. He does not pass a judgment, but instead leaves that to us to determine.

A second black cat (or perhaps it’s another bat?) crouches, peering at us from just behind the man, his direct stare drawing us in. Black cats often are shown prior to something occurring. They are not ‘bad’ in and of themselves but serve as a warning of something to come. Is its presence a further warning for us, the viewer, to ‘wake up’?

Alert and lying quietly to the right of the man is a lynx who watches as he slumbers. The lynx known for its strong vision and hearing, is said to carry supernatural properties and is also a symbol of secrets. His ‘awareness’ is keen, an absolute necessity for survival.

To further understand “The Sleep of Reason Produced Monsters in Asia” and the other four chromogenic prints, one must know something of Shonibare’s background. Yinka Shonibare was born in London (1962) and his family moved to what was a newly independent Nigeria when he was three, as part of the “newly elite”. Although raised in Nigeria, he spent summers in London and later attended Bm Shaw School of Art and then Goldsmiths College, receiving his Master’s in Fine Art. Being bicultural, he experienced the effects of colonialism all around him while growing up in Nigeria and although unknown previously to him, the searing effects of racism hit him while in England at school. These shaped the artist he was to become.

While in school, a tutor stated that his work did not reflect who he was, an African, and asked why wasn’t he producing authentic African art? This question coupled with his experiences growing up in different cultures and continents, along with his interest in the signifiers associated with mythology, laid a creative foundation which to this day, are at the heart of Shonibare’s work. In his paintings, sculptures, photography, film and installations he seeks to challenge implicit notions of authenticity, class, race and identity that are globally inherent in people’s thinking.

In 2004, Shonibare was offered the prestigious distinction of becoming a “Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire” (MBE). Some questioned whether he would refuse the honor given his work was often a critique of colonialism and the thinking of the time but he embraced it, feeling it “better to make an impact from within rather than from without” (Downey, #93), effectively making it a vehicle not unlike the Trojan horse. In 2019, the Queen further bestowed on him an even higher award, CBE, in the “Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire”, recognizing his great contribution to the culture and the arts.

Using references to well-known images in art lends a degree of power to these images, and Shonibare uses the “iconography of power to deconstruct power itself.” (Downey, Shonibare, p.45) as well as act “as a mechanism by which he can insert himself into the historical narrative, creating a place for himself within art history.” (Chambers, p.187)

“There’s the promise, or the fallacy, that enlightenment will liberate you, and that if you can forget your superstition and your religion and your culture you can be “like us.”(Goldstein, Artspace) Unfortunately, the narrowing of awareness also informs everything from our contemporary policies to the way we perceive others. “I think if we had a simple understanding that these places had their own systems of law and culture before the West arrived on their shores—if we had a mutual respect for everybody’s culture—it would be very nice. But instead we go on wanting to impose a 19th-century Enlightenment view on these people.” (Goldstein, Artspace)

There is a beauty and indeed a seductiveness in the colors and forms of “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters in Asia” but the fallacies presented in it transcend the “constructed boundaries of cultural and ethnic identity”, offering us “alternative realities” that challenge our assumptions. Within this ‘Trojan Horse’ are unsettling truths about society that await not only our consideration but also the reshaping and ‘awakening’ of our cultural narratives.

ENDNOTES

PHOTOGRAPHIC METHOD

First developed in 1942, chromogenic printing gained popularity during the 1980s. It spans both digital and chemical processes and prints are essentially made up of 3 monochromatic layers that have been combined into a full color image using silver crystals, called silver halide, which is most often used in the development of black and white images. Chromogenic prints can withstand approximately 60 years of light exposure, more than pigment prints but less than archival pigment prints.

SHARED INSPIRATION

Shonibare’s series restages the satirical suite produced by Spanish artist Francisco Goya y Luciente (1797-1799), The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, the 43rd etching in the suite, Los Caprichos. Like Goya, his work challenges assumptions of the day. Goya’s series was a bold critique of Spanish moral values, political corruption and the debauchery associated with the church, prominent during the Age of Enlightenment (1715 – 1789). During “The Age of Reason or Enlightenment”, European intellectuals marked an emphasis on reason and scientific method with increased questioning of the monarchy and religious orthodoxy, paving the way for the political revolutions of the 18th and 19th centuries.

“The Dream of Reason Produces Monsters” is a caption that admits of more than one interpretation in both artists work “When reason sleeps, the absurd and loathsome creatures of superstition wake and are active, goading their victim to an ignoble frenzy. But this is not all. Reason may also dream without sleeping, may intoxicate itself, as it did during the French Revolution, with the daydreams of inevitable progress, of liberty, equality, and fraternity imposed by violence, of human self-sufficiency and the ending of sorrow…by political rearrangements and a better technology.” (Huxley, p. 218-219) Goya, who moved in sophisticated circles of writers, artists and intellectuals, was courageous in his judgment on both his patrons and employers, even as he remained in their service. This could be seen as similar to how Shonibare has used his MBE and CBE status.

Both artists also experienced serious illness prior to creating their series – Goya became ill and it left him deaf for the remainder of his life and similarly, Shonibare experienced a disease that affected his mobility causing him to be hospitalized for a year and wheelchair bound for three before regaining some ability to walk despite leaving his left side impaired.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Welmoet (April) Glover in 2020.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Chambers, Eddie. Black Artists in British Art: A History from 1950 to the Present. (London ; New York: I.B. Tauris, 2014), 187

Kent, Rachel. “Yinka Shonibare MBE. (Sydney; Australia : Prestal, 2008), 45

Micko, Miroslav, and Roberta Finlayson Samsour. Francisco Goya Y Lucientes, Caprichos. (London: Spring Books, 1960), 7

Stilling, Robert. "An Image of Europe: Yinka Shonibare’s Postcolonial Decadence," 304

WEBSITES

Anonymous. “Yinka Shonibare MBE”. NMAFA.

https://africa.si.edu/exhibits/shonibare/intro.html

Downey, Anthony. “Yinka Shonibare by Anthony Downey”. Bomb.

http://bombmagazine.org/article/2777/yinka-shonibare

Fenstermaker, Will. “From C-Print to Silver Gelatin: The Ultimate Guide to Photo Prints”. Artspace.

https://www.artspace.com/magazine/art_101/collecting-101/whats-a-chromogenic-pigment-or-gelatin-

print-the-ultimate-guide-to-digital-and-chemical-photo-54752

Goldstein, Andrew. “Yinka Shonibare MBE on Art, Africa, and Why He's So Fond of the Queen”. Artspace.

https://www.artspace.com/magazine/interviews_features/meet_the_artist/yinka-shonibare-interview-52566

Harris, Elena. Owl Spirit Animal. Spirit Animal.

https://www.spiritanimal.info/owl-spirit-animal/

Huxley, Aldous. “Dream/Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, Franscisco Goya, 1799.

http://www.19thcenturyart-facos.com/artwork/dreamsleep-reason-produces-monsters

Madrid, Aurelio. “Yinka Shonibare”. EIL Escapeintolife.

https://www.escapeintolife.com/art-reviews/yinka-shonibare/

Mathiasen, Helle. “El sueño de la razon produce monstruos (the sleep of reason brings forth monsters)”. NYU Langone Health.

http://medhum.med.nyu.edu/view/12796

Pen, Dominique. Prospero's Monsters: Authenticity, Identity, and Hybridity in the Post-Colonial Age.

https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1051&context=africana_studies_conf

Rijks Museum. Owls.

https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/rijksstudio/subjects/owls

Stavrianou, Jennifer D. “Yinka Shonibare-Post Colonial Discord and The Contemporary Social Fabric Of 2017”. College of the Arts of Kent State University.

https://etd.ohiolink.edu/!etd.send_file?accession=kent1492814338595612&disposition=inline

Goya, Plate 43, "Los Caprichos": The sleep of reason produces monsters, 1799, etching, aquatint, drypoint, and burin, plate: 21.2 x 15.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)