Everett Shinn

American, 1873-1953

Sixth Avenue Shoppers, 1903

pastel and watercolor on board

21 x 26 1/2 in.

SBMA, Gift of Mrs. Sterling Morton to the Preston Morton Collection

1960.81

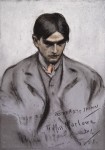

Self-portrait done in 1901 in his charcoal style.

RESEARCH PAPER

Sixth Avenue Shoppers shows the crowded sidewalk of one of New York’s major shopping avenues in the soft, late afternoon light of a winter’s day. At the left, women peruse merchandise at sidewalk stands; shoppers with bundles walk in the center; and a crowd of men and boys watch birds fight by the light of a simple lantern.

Early critics of Shinn’s pastels praised his fluidity of line but also noted how facile the pastels could be, often neither finished in conception nor execution. A story–probably apocryphal–is told about his major break into magazine illustration in late 1899 with a pastel of the Metropolitan Opera House in a snowstorm: After months of trying to have a drawing accepted for the center two-page spread in Harper’s Weekly, Shinn finally left a portfolio. Upon his return the editor, Colonel Harvey, asked to see him.

“You have here such a variety of New York street scenes,” the editor began, “that I was wondering if you have in your collection a large color drawing of the Metropolitan Opera House and Broadway in a snowstorm.” Shinn glanced out of the window at the falling snow, which would soon create the desired effect. “I think I have,” he replied. “Good,” snapped Harvey, “have it here at ten tomorrow morning.”

Shinn had his evening’s work cut out for him. On his way home, he purchased a fifty-cent box of pastels, then hurried to the Metropolitan Opera House to observe the architectural detail of its façade. Once home, he began to toy with the pastels, a medium he had not employed since his student days at the Pennsylvania Academy.

Shinn worked through the early hours of the morning. Shaky and pale, he delivered the finished drawing at the appointed deadline. Colonel Harvey stared at the artwork in silence. He scrutinized the lights twinkling dimly through the swirling snow, the dashing hansom cabs, and the scurrying ladies hoisting their voluminous skirts. “We have to decide on a price,” Harvey finally announced. “How about four hundred dollars and you own the original?”

Shinn had actually been producing pastels in New York before this. In early 1899, months before this episode, he had exhibited 48 pastels in his first one-man exhibition at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, including pastels of New York scenes. The most accurate part of the Harper’s Weekly story is Shinn’s ability in making quick perceptions and training his memory to record them. Both traits had been developed during his years as an illustrator for newspapers. Staff artists would accompany reporters on assignments and would have to be able to ‘turn in quickly’ accurate drawings for reproduction.

Just as Shinn had a remarkable memory for details, so too did he have a fine color sense. In Sixth Avenue Shoppers, he effectively creates an asymmetrical balance in an essentially frieze-like composition of figures in dark clothing through the use of one bright splash of vivid red in the dress of the woman with a muff. Moreover, he conveys the coldness of the atmosphere by liberally using light blue highlights on the snow-covered sidewalk. His method of using pastels was unusual and necessitated a complete balance already worked out in his mind before he began to draw. Edith De Shazo describes it well:

He took paper mounted on a heavy backing board and soaked it completely in a tub of water, removing excess water with his hand or a sponge. Then, with the final color composition completely in his mind, he began to apply patches of color. When these colors struck the wet ground, they turned immediately to a dark tone, losing their original coloration. Shinn worked swiftly and continued to build up his design until he had covered the whole surface. As the picture dried, the original color would return, but unlike the usual quality of pastel with its delicate, dust-like surface, evaporation of water caused the pigment to dry hard, producing brilliant color with a tempera-like quality.

It is difficult to date precisely Shinn’s pastels. His most brilliant ones are all from the period 1898-1911. In these early years, he was recording the activities of the bustling life of New York. He particularly loved the special effects of weather or light, and night scenes are among his most telling works. Although it was dated in 1959 by Shinn’s dealer as circa 1925, the costumes of the women in Sixth Avenue Shoppers would date it between 1905 and 1910.

EVERETT SHINN

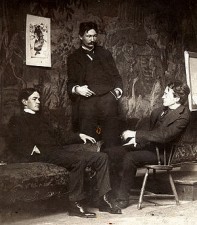

In 1891 at the age of 15, Everett Shinn left his native town of Woodstown, on the southern tip of New Jersey, for Philadelphia. There he studied mechanical drawing and worked briefly designing light fixtures for the Thackery Gas Fixture Works. In 1893 he began classes at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, studying under Thomas Anschutz. He soon became friends with fellow students Ira Glackens and John Sloan. In the same year, he started work as a staff artist for the newspaper Philadelphia Press. George Luks was already on staff and by 1895 the two were joined by Glackens and Sloan. All four came under the influence of Robert Henri.

In 1895, Shinn moved to New York City to work at the New York World where by 1904 he was joined by his three Philadelphia newspaper artist friends. It was in the early New York years that Shinn began to receive public attention. His first one-man exhibition was held in January of 1899 at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts with 48 pastels. These same works were exhibited a year later, in 1900, in New York at the Boussard Valadon Gallery where 10 were sold. Shortly after the opening, Shinn made his only visit to Europe, spending time in London and Paris. In 1901, he held his second exhibition in New York at the same gallery, showing pastels, and drawings of Europe. From then until 1911, he exhibited widely.

Shinn, in the most purple prose, wrote in 1944 of the New York art world in the first decade of the century:

It (was in) a state of staggering decrepitude . . . It was disciplined in an order of sameness, effete, delicate, and supinely refined. It revealed its pale countenance with the elegance of plush-lined shadow boxes in shrines and gilt grottos. Art galleries of that time were more like funeral parlors wherein the cadavers were displayed in their sumptuous coffins.

One day an incredulous stare came into its imported plate-glass eye which had for a decade mirrored only lorgnettes and fawning patrons. For there on its velvet lawn stood a bedraggled group of invaders. The Eight had wandered in. The interlopers paused and removed their hats. The solemnity of death had caught at their scant respect. The Eight had journeyed out to see life and found themselves in a morgue.

In reaction to the “cadavers” of contemporary painting, the four former Philadelphia artists with Robert Henri, then too in New York, and Ernest Lawson formed in April of 1907 the nucleus of “The Eight” or “Ashcan School.” They were soon joined by Arthur B. Davies and Maurice Prendergast. In February of 1908, “The Eight” opened an exhibition at the William Macbeth Gallery. Greeted with derision in New York, the exhibition traveled to good reviews in Philadelphia, Chicago, Buffalo and Toledo.

During the years that Shinn and his friends were attacking the established art world, he was also dabbling in theatricals. He built a small theater in his studio and established a group he called, after his address, “The Waverly Street Players.” Shinn was the impresario playwright, director and producer as well as scene painter. Among the plays produced were Lucy Moore or The Prune Hater’s Daughter, Ethel Clayton or Wronged From The Start, and Hazel Weston or More Sinned Against Than Usual.

By 1912, Shinn had become more and more preoccupied with his career as a decorator. He had met in 1899, the year of his first one-man exhibition, Clyde Fitch, the playwright, and Elsie de Wolfe, the decorator. Through them he met David Belasco and Stanford White, for whom he was soon painting murals and decorations. Shinn’s specialty became murals in the manner of Louis XV, and his style was referred to ironically by his friends as “Rococo Revivalism.” Indicative of Shinn’s artistic goals by 1913 is the fact that when he was asked to participate in the Armory Show, he never even answered the invitation.

In 1912, Shinn was divorced in a widely publicized suit by his first wife (he married four times). A year earlier, he had served as a model for the bohemian painter hero of Theodore Dreiser’s novel The Genius, a book in which contemporary gossip said the author had used Sloan’s paintings, Shinn’s studio, and Dreiser’s life. The two men had known each other through Shinn’s work as an illustrator for several magazines of which Dreiser was the editor.

Shinn’s work for magazines began in 1900 when he succeeded in having a pastel used for a double spread in Harper’s Weekly. From then onwards, he was a prolific illustrator, altering his style to meet the demands of a changing public. In the twenties and thirties, for example, his figures became elongated with a bloodless sophistication. In 1917, he branched out into the new movie business, becoming art director for Goldwyn Pictures in New York. He worked actively for studios until he grew tired of producer William Randolph Hearst’s constant interference while he was working on Janice Meredith, a vehicle for Marion Davies.

In the late 1930s and 1940s, Shinn returned after a twenty-year hiatus to his original Ashcan subjects–scenes from the active life on New York streets. His most famous works from this period are the murals in the Men’s Bar of the Plaza Hotel of Central Park. These works, however, lack the early empathy with people and their surroundings.

From the paper A History of American Art prepared by Mrs. Joseph E. Knowles in connection with the Young People’s Art Program, SBMA Docent Files.

Prepared for the Docent Council website by Tracey Miller and edited by Lori Mohr, fall 2012.

Ashcan School Artists, circa 1896. L-R: Everett Shinn, Robert Henri, John French Sloan