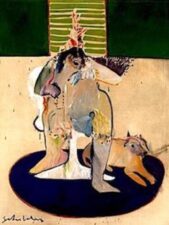

Fritz Scholder

American, 1937-2005

Indian with Three Faces, 1970

acrylic on canvas

46 ½ x 25 ½ in.

SBMA, Gift of Mrs. I. C. Kellogg

1971.56

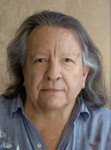

Fritz Scholder in his studio in Santa Fe, NM

“The positive does not exist without the negative, and the role of the artist is not to compromise, but to express the truth as he sees it with all the power of which he is capable.” - Fritz Scholder

RESEARCH PAPER

Painted in 1970, Indian with Three Faces is an excellent example of Fritz Scholder’s mature work on the subject of Indians. Smaller in scale than many of his canvases, it nonetheless is typical in its technique, composition, iconography and color.

Fritz Scholder was born in Minnesota on October 6, 1937 of French, German and Luseno (California Mission) Indian ancestry. His father worked as an administrator for the Bureau of American Affairs, a position which necessitated many moves on the part of his family. The family’s Indian background was not stressed, and it was not until Scholder’s involvement with the Southwest Indian Arts Project in Tucson in the early 1960s that he began to identify with his Indian heritage. Even then he refused to paint Indians because he felt that the sentimental picture given by traditional Southwest Indian painters debased their culture.

Scholder’s art education began early; in high school in Pierre, South Dakota, he studied with Oscar Howe, the well known Sioux artist. Howe had lived in Paris and painted in the Cubist manner. Another primary source was the Pop artist, Wayne Thiebaud, with whom Scholder studied for two years while attending Sacramento City College. Francis Bacon, Nathan Oliviers, Richard Diebenkorn, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg have all been influences upon Scholder’s work. Bacon inspired “monsters of crushing terror”. Oliviera implied motion in what would generally be a static figure; Diebenkorn: linear structure; Johns and Rauschenberg: paint handling and textural qualities.

In 1960 Scholder received his BA and moved to Tucson where he became a graduate assistant at the University, teaching drawing and design. There he became associated with the Southwest Indian Project for the Rockefeller Foundation. In 1962 he was given a John Hay Whitney Opportunity Fellowship and awarded the Ford Foundation Purchase prize. In Santa Fe, New Mexico in 1967, Scholder painted his first Indian painting. Quickly gaining in authority and vitality, he soon became recognized as the leader in the “new Movement in Indian Art.” Scholder said, in 1972, “I believe . . . that there is a new Indian art emerging. It will take many forms and will be vital. A merging of traditional subject matter with the contemporary idioms will give us a truer statement of the Indian.” Thus Scholder’s Indians avoid the ethnic cliché of the “noble savage.” They are radical pictures of the American Indian – abstract expressionist in technique, surrealist in content, with elements of Pop. His figures have dignity, monumentality, and earthy vitality. Sometimes he injects humor or satire. There is never any condescension or romanticizing. Instead of gazing sadly or nobly into the distance, Scholder’s Indians have expressions of rage, menace, and madness. Pattern is strong with many closed and solid forms. Distortion for emotional impact is a frequent device. Color, which Scholder considers his strongest weapon, is vibrant and unorthodox.

“Color,” Scholder says in an interview with Joe Callahan for Elaine Horwich Galleries in Scottsdale, “is very personal, first of all. We all perceive differently from our own frame of reference. . . we go to school and teachers make sure to inhibit us . . . what colors clash and color wheels, and this goes with that and none of it makes any sense. There is an old saying, ‘Have you ever seen a flower garden clash?’ And I believe it! Color is color . . . anything goes”. In Scholder’s work or in his painting color is used to define form, contrast is high, the hues are bright without being pure. Scholder works quickly and in isolation. He describes his painting state as somewhat trance-like.

While Scholder’s Indian paintings often include the traditional images associated with Southwest Indians – horses, dogs, feathers, blankets, jewelry, war paint, peace pipes, tomahawks, teepees – they also introduce other images which are considered heretical – umbrellas, cats, beer cans, the American flag, dark glasses, automobiles, ice cream cones. Scholder points out that these contemporary objects, however unorthodox they may seem to viewers conditioned by the traditional Southwest Indian painters, are nonetheless a real part of the Indian as he tries to come to terms with the present. For Scholder, the key word for the Indian today is “Paradox” - the paradox of being caught between two cultures – that of his history and traditions and that of the dominant society in which he must function.

In 1973 Scholder identified five categories of Indians in the Indian paintings: Monster Indians, Present-day Indians, Cowboy Indians, Indian massacres and Gentle Indians. In 1977 he classified the phases as: monster Indians, Indians on Horseback, the Dartmouth Portraits, and the American Portraits along with contemporary Indians in Gallup and “most recently “ the Indian Postcards.

Indian with Three Faces is a painting of a single closed figure seated – but without any sign of seated on what. The body of the Indian is a triangular form filling much of the available picture surface. Three different faces share the shoulders, and a pair of elliptical shapes jut out from either side of the combined heads. The Indian is dressed in a long dun-colored robe with a sleeveless chartreuse overshirt and a blue vest. He holds an orange peace pipe and a gray feather in his right hand; this hand rests on the knee which is slightly lower than the left. The left hand rests firmly on the left knee, and over the knee is a narrow Navaho rug. The Indian is wearing moccasins with round patterns. The top half of the painting is orange-red, the bottom half is a dark blackish color; drips from red have been spattered on the figure and on the bottom of the painting. The highly saturated red background is overpainted up to the figure and delineates it. The three faces for which the painting is named appear on first glance to be three orientations of the same face. Closer examination, however, shows them to be only tenuously related. The primary face stares out at the viewer with little flesh-encased eyes; its teeth are bared and clenched; its nose is grotesquely snubbed; its color is unnatural. It reminds us of Goya’s monsters in its deformity, madness and menace. The second head is directly behind the first and only a small part of it shows in profile. This part is chinless and ill-defined; it has a single black-rimmed eye. Behind this face is the third – this one is better drawn and is clearly the profile of a rabbit. Two curved forms which may be ears or may be feathers stick out from the heads on either side. The right ear/feather is partially cut off by the edge of the canvas. There is something profoundly disquieting about this figure with its three faces, any one of which, by itself, is too small for the body, but which, collectively are in good proportion. The tilt of the body to the left and the position of the knees – one higher than the other – imply movement. The viewer wonders what is the true function of the appendages which should be feathers if this is an Indian or ears if this is a rabbit. What is the viewer to make of his feeling that the most human face is the most frightening, the most animal, the most benign? We are witnessing a transformation of human to animal as in a shamanistic rite; but these ancient practices have no place in the alien culture – the Indian is disoriented, disturbed – disturbing.

As a composition Indian with Three Faces functions beautifully to create an emotionally charged painting and a visually dynamic one. The diagonals formed by the ear/feathers, the peace pipes, and the rug zig-zags across the surface contrasting with the static figure of the Indian. A play of light and darks on the canvas keep the eye in movement. We would like to rivet our attention on the subject matter but cannot.

Scholder’s iconography depends greatly on the triangle. This shape – either embodied by the central figure itself or as a strong compositional element organizing space, or, even more obviously, as a teepee or a road vanishing into the horizon – is the means by which many of Scholder’s works convey the feeling of monumentality and balance. Sometimes the triangle is set off to one side; more often its base is formed by the lower edge of the canvas and the triangular figure takes a central place in the composition. Other images which appear so frequently that they gain iconographic status are: the feather, the peace pipe, the Flag, Coors beer cans, Indian dogs, Indian horses and dark glasses.

The Santa Barbara Museum of Art’s acquisition is a fine example of Fritz Scholder’s Indians. In its expressionist technique, its Indian subject matter, its deliberate emotion, its iconography, its powerful and unusual color it conforms to those qualities recognized as typical in Scholder’s mature canvases. It is closely allied to – and of equal quality with – his better known and more widely reproduced Buffalo Dancer, Indian in Gallup, Screaming Indian, and Indian in Transition.

Margie Celini April, 1978

Transcribed by Virginia Cornell, 2004

POSTSCRIPT

The Ridley-Tree Gallery with its rotations from the permanent collection continues to provide reunions with many of our major works. So I was delighted to find Fritz Scholder’s "Indian with Three Faces" on display. My sister MollieO introduced me to his work after she saw his paintings in San Francisco and visited his studio in Scottsdale. I have been drawn to his work ever since. He is a powerful, assured artist with all the daring and passion of post-modernism.

Because he is able to represent his experience graphically, we need no background to enter his work. It is immediately clear that this is no idyllic Indian Chief. The background of broken/slashed scarlet strokes feels frantic, unsettled, hysterical, yet the figure is almost vague, cloaked in a bland shroud, prominently floppy rabbit ears askew. The face is blurred, reticent, almost secretive. As we observe, three faces emerge, and in my experience also reabsorb into the background: two animalistic profiles and a quietly anguished frontal face. The only details are given to two traditional Indian artifacts, a peace pipe and native woven, fringed scarf.

In Indian thought each person has his own animal identity. Our quiet, shy rabbit man shows us not only the artifacts we associate with his tribal heritage, but also his alienation, suffering voiced as a silent moan. One image captures both sides of Native American life: the widely admired crafts and myths and the desperation of tribal disenfranchisement.

Fritz Scholder saw himself as an artist from early childhood, but didn’t see himself as an Indian artist until the late 1960s. But it is a new Indian artist he embodies. In interviews with the Smithsonian in 1970 he said; “Upon my arrival in Santa Fe in 1964, I vowed that I would not paint the Indian. The non-Indian had painted the subject as a noble savage and the Indian painter had been caught in a tourist-pleasing cliché.”

Later he wrote, ”I retracted my vow of 1964 for several reasons, one of revisiting Fritz Scholder’s ‘Indian with Three Faces’, these being a teacher’s frustration on seeing a student with a good idea fall short of the solution. After class the immature struggles with paint and concept haunted me. One winter evening early in 1967 I decided to paint an Indian.” “Although I never called myself an Indian artist, it soon became evident that it was time for a new idiom in Indian painting.”

Fritz Scholder (1937-2005) grew up in Minnesota, son of a German/Indian father, himself one quarter Luiseño, a California Mission tribe, though he did not identify with the Indian traditions until later in life. In grade school, first in Minnesota and then in North Dakota, his artistic talent was recognized and encouraged, and he studied art in college, first in Wisconsin and later in Sacramento, when his family moved to California where he studied with Wayne Thiebaud, who introduced him to Pop Art and shared in his first cooperative gallery show to enthusiastic reviews. Offered an internship at the Univ. of Arizona in Tucson, he taught and completed his MFA there in 1964 before accepting a teaching post at the newly formed Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe. Many national and international exhibitions followed, highlighted by his show at the Smithsonian Museum of American Art in 1970. Most of the images and interviews in this article come from that catalogue.

In 1972, Scholder developed an extensive adobe-walled compound in Scottsdale, Arizona, at the same time exhibiting throughout Europe and the United States and traveling extensively to collect artifacts, receive honorary degrees and absorb the work of European artists. Chief among these was the painting of Francis Bacon, with whom he felt a connection. We see the presence of Bacon’s irreverence and darkness in Scholder’s figures, including in our own "Indian with Three Faces". The expression of deeply held anguish is profound in “Indian and Contemporary Chair”, so much so we almost have to look away. We identify the figure as female from the arm with bracelets, raised as if fending off a blow. The plastic chair separates her from the earth and offers her no protection. This raw confrontation with domestic violence, one of the most grievous ills in modern reservation life, becomes the artist’s subject. Scholder wrote in 1970: “But the positive does not exist without the negative, and the role of the artist is not to compromise, but to express the truth as he sees it with all the power of which he is capable.”

Fritz Scholder died at 67 of diabetes, at the height of his artistic powers.

- Ricki Morse, “Revisiting Fritz Scholder’s Indian with Three Faces, 1970”, La Muse, September, 2019

Fritz Scholder, Indian and Contemporary Chair, 1970, oil on linen, Smithsonian