John Singer Sargent

American, 1856-1925 (active France, England)

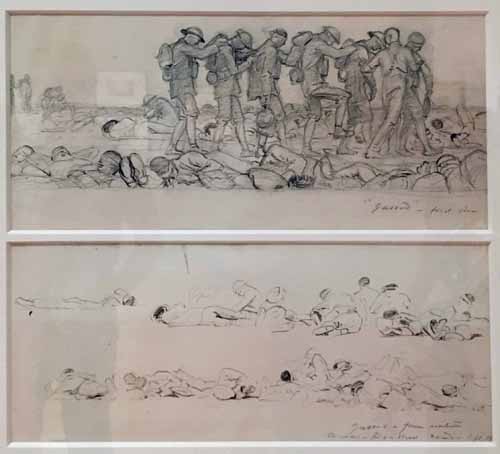

Two Studies for “Gassed”, 1918

ink on paper

6 1⁄2 x 14 1⁄4 in. ea.

SBMA, Gift of Lucius B. Manning

1955.29.1-2

Undated photo of Sargent

"While at the casualty station he witnessed an orderly leading a group of soldiers that had been blinded by mustard gas. He used this as a subject for a naturalist allegorical frieze depicting a line of young men with their eyes bandaged. Gassed soon became one of the most memorably haunting images of the war." (Spartacus Internet Encyclopedia) As always, Sargent had been interested in painting the truth. Here, an actual picture of soldiers lined up after a mustard attack.

Gassed (1919) by John Singer Sargent Imperial War Museum, London

COMMENTS

Object Description

image: a study of the second line of gassed British infantrymen as depicted in the oil painting 'Gassed'. The line is made up of eight gassed soldiers led by a medical orderly, one of the rearmost soldiers leaning over to vomit. In the top left is a study of a medical orderly holding the right arm of a gassed soldier.

A side on view of a line of soldiers being led along a duckboard by a medical orderly. Their eyes are bandaged as a result of exposure to gas and each man holds on to the shoulder of the man in front. One of the line has his leg raised in an exaggerated posture as though walking up a step, and another veers out of the line with his back to the viewer. There is another line of temporarily blinded soldiers in the background, one soldier leaning over vomiting onto the ground. More gas-affected men lie in the foreground, one of them drinking from a water-bottle. The crowd of wounded soldiers continues on the far side of the duckboard, and the tent ropes of a dressing station are visible in the right of the composition. A football match is being played in the background, lit by the evening sun.

The scene is the aftermath of a mustard gas attack on the Western Front in August 1918 as witnessed by the artist. Mustard gas was an indiscriminate weapon causing widespread injury and burns, as well as affecting the eyes. The painting gives clues about the management of the victims, their relative lack of protective clothing, the impact and extent of the gas attack as well as its routine nature The canvas is lightly painted with great skill. Sargent draws the viewer into the tactile relationships between the blinded men. There is a suggestion of redemption as the men are led off to the medical tents, but the overall impression is of loss and suffering, emphasized by the expressions of the men standing in line. Sargent travelled to France with artist, Henry Tonks in July 1918. Tonks describes the context for this work in a letter to Alfred Yockney on 19 March 1920: 'After tea we heard that on the Doullens Road at the Corps dressing station at le Bac-du-sud there were a good many gassed cases, so we went there. The dressing station was situated on the road and consisted of a number of huts and a few tents. Gassed cases kept coming in, lead along in parties of about six just as Sargent has depicted them, by an orderly. They sat or lay down on the grass, there must have been several hundred, evidently suffering a great deal, chiefly I fancy from their eyes which were covered up by a piece of lint... Sargent was very struck by the scene and immediately made a lot of notes.' Sargent was commissioned by the British Government to contribute the central painting for a Hall of Remembrance for World War One. He was given the theme of 'Anglo-American co-operation' but was unable to find suitable subject matter and chose this scene instead. ' The further forward one goes', he wrote 'the more scattered and meager everything is. The nearer to danger, the fewer and more hidden the men - the more dramatic the situation the more it becomes and empty landscape. The Ministry of Information expects an epic - and how can one do an epic without masses of men?'

History note from Ministry of Information commission, 1918

Inscription John S. Sargent Aug 1918

Imperial War Museum

http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/23722

It is a curious processional of sorts, from left to right, solemn, grave, almost religious; pathetic, too, in the way that hands reach out to touch shoulders. The side-on view transforms it into something almost sculptural – a species of low-relief frieze from Hellenistic times, for example, which might be the enactment of some homage to a god. And yet the direction of travel is entirely directed by a medical orderly. Otherwise, it would be a vague forever-onwards blundering along a duckwalk to a neverland.

What shocks us almost more than anything else is the fact that it is John Singer Sargent who has made this work of art. It seems quite contrary to how we almost always think of him, that American master of the bravura brushstroke; that fashionable painter of drawing-room equipoise; that dealer in – and doler out of – easily persuasive flattery on the grand scale.

We never think of Sargent in the context of the depiction of human suffering. And yet the man was there, in the midst of war, at the age of 62. He had been sent there, to France, by the British Government to do justice to the sobering horrors of conflict, and, unsurprisingly he was in several minds about an appropriate subject at first because, well, this was not Sargent's habitual terrain, as we have already noted.

He witnessed the scene with his own eyes, the aftermath of this terrible gas attack. When it was done and displayed – it was nominated picture of the year by the Royal Academy – not everyone liked it. E M Forster thought it too heroic by half. Forster has missed the point, surely. It is indeed on a heroic scale, and its gigantism – including the fact that it is so much wider than it is high –adds a kind of plangent cinematic forcefulness to the scene, but its theme, all the same, is the brokenness, the helplessness of humanity in the face of barbarous devices. Terrible things are often slightly serio-comic too, and so it is here. This is a kind of strange perversion of blind's man's bluff, isn't it? And yet these bandages are for real. These men may never see again. They may not even survive at all.

They are being led, with their eyes swathed in lint, towards a treatment tent – see those guy ropes. There is more than one line of men. They are converging from several directions. And, meanwhile, other things are going on too. In the far distance, a game of football is being played. Back left, we can see tents. There is a hanging moon. The light is a strangely grainy mustardy yellow – with just a tint of rose – that suffuses everything. We can almost smell the air.

Heroism? That jumble of broken and helpless men that occupies the entire foreground of the painting, and continues behind the stepping men, makes that claim even less credible. All this is human flotsam and jetsam, done down by the nastiness of war. The soldiers have been felled, bludgeoned to the ground, by some hellishly new-fangled and treacherous poison that they are helpless to resist. No steely, cocksure weapon can save them from such as this. Some of these men have been set back up on their feet, frail, confused, awkward, and are being led away. One – the third from the front – looks like a high-stepping puppet. Perhaps he has just frightened himself by stumbling against that duckboard. Many are not so fortunate. They are not moving at all. This is Owen country: the pity of war.

When we think about paintings of the First World War, we often choose to batten down upon some of the more experimental works by Boccioni, Nevinson or Lewis, works that owe a debt to Cubism, Futurism, and Vorticism. The very fact that these works belong among the achievements of the moderns lends them an atmosphere of excitable timeliness, as if up-to-the-minute art is proving that it can deal with the greatest of catastrophes. Art is keeping pace with the horrors of modernity. This painting by Sargent belongs to an older tradition of narrative realism. It claims kinship with the narrative paintings of a great Russian like Repin. It possesses a kind of trudgingly profound and monumental sobriety.

John Singer Sargent was the scion of a couple of nomadic Americans. Before his birth, his father had practiced as an eye surgeon in Philadelphia. John was born in Florence and, like his parents, spent his life on the move – Corfu, the Middle East, Florida... He trained with Carolus-Duran in Paris, and, well mannered and speaking perfect French, he soon became a society painter in great demand. Henry James found his precocious talent "unnerving".

- Michael Glover, Friday, 31 May 2013

Independent.co.uk