Lucas Samaras

Greek, 1936- (active USA)

Reconstruction #107, 1979

sewn fabric on canvas

83 1/2 x 76 3/4 in.

SBMA, Gift of Alan Shayne

1998.75

Lucas Samaras, Self Portrait, manipulated photograph

“I cannot separate beauty from pain.”

“Making art was essential. It was the distillation of my distance as well as the backboning of my sloppy sentimentalizing. It was also passport and proof. I was an intruder who had attached to his baggage stickers of ancient glories. It was essential to fill the bags as soon as possible with modern equivalents.” – from ‘On Immigrancy’

RESEARCH PAPER

Reconstruction #107 is numbered the 107th in a series of sewn patchworks mounted on large rectangular canvases which Lucas Samaras made in the late 1970s. He began this series in 1976, the year after his mother died, as a tribute and remembrance. Consistently autobiographical in his work, Samaras included letters, symbols and fabrics with personal meaning in the first of these constructions. The project expanded when he discovered in fabric stores “knock-offs” related to recent art movements such as op art and abstract expressionism. He was attracted to inexpensive, cheesy, and even gaudy fabrics, which he turned into an artistic medium by loosely sewing strips of cloth to the canvas. The psychedelic and optical quality of these works is reflective of the 70’s. Samaras suggested that the Reconstructions psychologically “envelop you, soft and soothing,” perhaps giving you “some bad dreams, but at the same time stroking you." Jay Grimm of Art News said the works “look like the giddy effects of a quilting bee on acid—raucous tributes to kitsch and craft.”

Looking at the Reconstructions for formal elements is like finding “logic in a crazy quilt,” as one critic put it. The fabrics in Reconstruction #107 are placed diagonally over and under each other for optical effect: which fabric is forward, which is back? Which fabric “pops?” The diagonals surround angular areas of more intense interaction, kaleidoscopes made from smaller pieces of fabric containing flashes of color. Left of center, a bright green contrast catches the eye; upper left center and lower right are small clashes of pink. Careful examination of the fabrics in these areas reveals see-through polyester and glitter components. Repetition of an orange-outlined geometric cloth holds the work together. This fabric is an op-art knock-off containing black and orange crosses upon a green ground. It interacts with a bold black and white abstract print to create tension, and large strips of bold black tinseled fabric overlie the whole. It is difficult to find a place for the eye to rest in this visually dynamic fabric collage.

Lucas Samaras was born in Kastoria, Macedonia, Greece, on September 14, 1936. He immigrated with his family to the United States in 1948, after witnessing first-hand some of the horror and deprivation of World War II. He studied art at Rutgers University from 1955 to 1959, where he had several solo shows. His first commercial exhibition was at the Reuben Gallery in New York in 1959, and he became involved in the activities of other artists associated with the gallery such as Claes Oldenberg, Jim Dine and Red Grooms. He performed in some of their first “Happenings.” In 1960 he stopped painting in oils and began working on pastels, assemblages and boxes. One of his boxes was shown in the exhibition “Art of Assemblage” at the Museum of Modern Art in 1961. In 1966 he exhibited his Mirrored Room at the Pace Gallery in New York. His mirrored “Corridor,” 1967, which visitors walk through, can be experienced at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

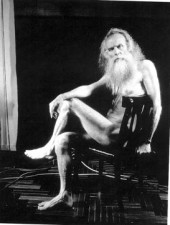

Working in New York City for five decades, Lucas Samaras has been productive in many mediums. However, photography is primary, and the almost 400 works included in his second retrospective exhibition at the Whitney Museum of Art in 2003-4 (the first exhibition was in 1972) were mainly photographs and boxes. The exhibition was entitled "Unrepentant Ego: The Self-Portraits of Lucas Samaras." The boxes, like the photographs, are self-referential and most contain his image in some form. Some of the boxes glitter with pins, nails, or costume jewelry, displaying the same decorative flair and the use of unexpected materials as the sewn Reconstructions. Some are reminiscent of the boxes of Joseph Cornell with objects like marbles, feathers, mirrors and toys placed inside, creating what one critic describes as “precious, message-laden relics.” In the 1970’s Samaras also began making what he calls “photo transformations” by manipulating Polaroid emulsions before they are fixed. Currently (2005) Samaras is a recluse in his Manhattan apartment, where he still makes thousands of photos which he may digitally alter and deconstruct, most of them exploring the changes of his aging face and body.

Mark Stevens of New York Magazine has the following explanation for Samaras’ self-absorption:

“Samaras seems to look into a hot, murky, turbulent cauldron. He finds as much self-loathing there as self-love. More important, he is essentially a religious artist—and not one who builds a cathedral to himself. He is instead the modern reincarnation of a Byzantine hermit in a cave, an artist who stares into “the self” the way a monk relentlessly, desperately, longingly, convulsively, idiotically, boringly stares into a skull—searching for something beyond reason’s body.”

Samaras is still considered and has been considered during all of his long career to be a cult artist with “outsider” status, although he has been represented nearly 40 years by the Pace Gallery, a New York powerhouse. Vince Aletti, art critic for the Village Voice, sums it up this way: “Samaras always seems to be screaming "Love me! Love me!" and muttering "Fuck you" under his breath.” But the artist’s contradictions, Alleti maintains, do not detract from the work, which is “self-contained, sophisticated, and relentlessly experimental,” which accurately describes the Santa Barbara Museum’s Reconstruction #107 considered as a 1970’s work of art.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Ellen Lawson, Feb. 2006.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

“I Examination,” Vince Aletti, Village Voice, December 1st, 2003

“Lucas Samaras,” Jay Grimm, Art News, Summer 1999

“Lucas Samaras’ Artist’s Biography,” Pace Wildenstein Gallery

“Lucas Samaras: Whitney Museum of American Art, New York,” Jeffrey Kastner, ArtForum, March, 2004

“Me Veneration,” Mark Stevens, New York Magazine, December 1, 2003

POSTSCRIPT

Art Review, Me Veneration

Lucas Samaras’s favorite subject is himself—but as the Whitney’s huge retrospective reveals, he sees things you might not expect in a narcissist.

By Mark Stevens

Unrepentant Ego: The Self-Portraits of Lucas Samaras opens with this quotation from the artist: “Professional self-investigation—which is what a good self-portrait is—is as noble a search as any other, and I have always shared what I have learned with the public.” The use of the word noble is slyly defensive, as is that of unrepentant in the exhibition’s title. They suggest a concern that viewers may find something ignoble—something that should be repented—in Samaras’s art. That something is, of course, narcissism. For most of his life as an artist, Samaras has focused upon himself with an intensity that goes well beyond “professional self-investigation.” He has made thousands of Polaroids of his face and body; he has a childlike love of glitter and a morbid preoccupation with the decay of the body; his significant other is himself. Alone in his Manhattan apartment, he permits no one to come between him and his object of desire, creating a me-myself-and-I theater of the self in which he claims every role. The “noble” narcissist casts himself as performer, audience, critic.

Lucas Samaras Self-Portrait, June 6, 1996 Published in Aperture Magazine, Summer 2002 "When you get older, you say, 'Okay, now it's time for me to play Lear." So I had to play it, and I would photograph it. . . . you give yourself the opportunity of resigtering the way you look at this particular time, and making it look the way you want it to look. . . ."