Kay Sage

American, 1898-1961

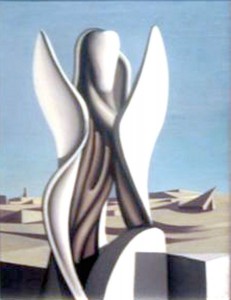

Second Song, 1943

oil on canvas

24 x 18 in.

SBMA, Gift of Estate of Kay Sage Tanguy

1964.32

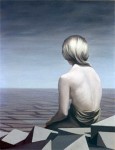

Kay Sage, "Le Passage (The Passage)," 1956, oil on canvas, 36 x 28". Kay Sage expresses in this painting her sorrow at the death of her husband, Yves Tanguy, the great surrealist painter.

RESEARCH PAPER

Kay Sage was a well-known American Surrealist. Like many of the Surrealists she was a poet as well as a painter. She was married to Yves Tanguy, one of the foremost French Surrealists, and thus her accomplishments may have been overshadowed by his.

Katherine Linn Sage was born into the wealthy family of Henry Manning Sage, a New York State Senator. In 1900 her parents separated, and Kay and her unconventional and restless mother traveled between the United States and Europe. Kay attended many schools and became fluent in English, French and Italian. In the 1920s, as a beautiful young woman, she met and married an Italian prince. The marriage lasted ten years. She then moved to Paris and lived a Bohemian life. There she met the Surrealists and began to paint abstract pictures.

It was in Paris that she met Andre Breton who was impressed by the strength and thought of her paintings. Breton was the self-appointed leader, spokesman and critic of the Surrealists. Breton wrote that “surrealism had one foot in automatism and the other in the dream.”(1) Literature, medicine, psychoanalysis and the ideology of political revolution influenced the Surrealists. Europe at this time was overwhelmed by catastrophe. The Surrealists expressed feelings of universal desolation. Another Surrealist Kay Sage admired was the Italian, Giorgio de Chirico. His paintings express the anxieties found in our century, unexpected jumps in scale, backward glances at antiquity, unfathomable architecture and strange combinations of unrelated objects. Kay Sage’s paintings display his influence.

Kay met Yves Tanguy in the late 1930s. They moved to the United States and were married in 1940. They lived in the artistic community of Woodbury, Connecticut. Here they painted separately but happily until his death in 1955. His work influenced her, but she profited and went her own way.

In 1958 her eyesight began to fail due to cataracts and she ceased painting. She did some constructions or Surrealistic game boards which used combinations of glass, beads, reeds, rocks and other small objects. These games were concerned with space, shape and shadow. She was despondent and attempted suicide twice. She succeeded the second time shooting herself fatally in 1961.

Style: A devoted friend, Regine Tessier Krieger, said Kay Sage never talked about her paintings. She would say “Let them talk for themselves.”(2) Their distinct messages come through in her treatment of infinity, space and obstacles. Her arid landscapes look extraterrestrial and recede through curious geometric forms toward infinity. Her structures appear uninhabited except for shadows. Fairfield Porter, art critic for Art News, wrote that her worlds are not inhabited by creatures, only by ghosts intent on purposes which are not understandable.

Sage felt her perspective treatment of space developed when she painted on the great plains surrounding Rome. She saw the city from a great distance or from down a long road. The scale is uncertain. You can’t tell how large the images are. The Museum’s painting Second Song is typical of her work during and post World War II. The central figure of a draped “goddess” or “angel” has a monumental, protective quality about her. Space interpenetrates her form so that one can see through to the abstract landscape and sky beyond. Her inner substance has an organic roundness suggestive of femininity. The ovoid, featureless head is seen in her other paintings as well.

There is an interesting contrast between the bold, flowing curves of this female figure and the sharply delineated and precise structures beyond. Sage uses Cubist inspired forms to create a Surrealistic effect. The repetition of these geometric forms sets up unity and rhythm creating balance in the lower pictorial area. The outward thrust of a small triangular structure to the right of the “angel” combined with her forward facing position balances her left of center placement.

The large area of clear aqua sky is in sharp contrast with the pure white wings but the total effect is balanced. The monochromatic scheme of gray shadows and earthen tones of clay, khaki and pale yellow in the landscape does not distract from this strong contrast. The colors become less intense toward the background. The light source appears to come from the front right leaving shadows of gray and charcoal on opposite surfaces. A marked difference in values on these surfaces gives a strong three-dimensionality.

The linear quality of this painting is further enhanced by the precise definition of flat color areas. The weave of the canvas can be seen and there are very few noticeable brush strokes. Typically, Sage seems to use color to emphasize form and space.

After the death of Kay Sage her paintings were distributed to museums throughout the United States as designated by her will. Second Song in our collection demonstrates the Surrealist attributes of an abstract dream world, unfathomable architecture, the combination of unrelated objects, a Freudian image of woman, and infinity. Because she never spoke about her paintings, their intended symbolism may elude us. We might conjecture about the “Second” in her title referring to World War II, which was raging at the time. The palpable rhythm could suggest a “Song” or message. No matter what interpretation is reached, her art creates it’s own serenity and eloquence.

(1) John Russell, The Meanings of Modern Art, Harper and Row. New York, 1974. P. 195

(2) Regine Tessier Krieger, Kay Sage, 1977, unpaginated.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Joanne Adamowski, March, 1984

Website preparer: Fran Adams, March, 2004

Bibliography:

Baron, Michael, “Fifty-Seventh Street in Review,” Art Digest, Vol. 22, No. 2, October 15, 1947, p. 22.

Campbell, Lawrence, “Reviews and Previews,” Art News, Vol. 59, No. 2, April 1960, p. 14.

Campbell, Lawrence, "Reviews and Previews", Art News, Vol. 57, No. 7, November 1958, p. 14.

Canaday, John, Mainstreams of Modern Art. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1959.

Dorra, Henrik, Art in Perspective. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc.

Feldman, Edmund Burke. Art as Image and Idea. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1967.

Levy, Julien, “Tanguy Connecticut Sage,” Art News, Vol. 53, No. 5 September 1954,pp. 24-27.

Lonngren, Lillian, “Reviews and Previews,” Art News, Vol. 60, No. 2, November 1961, p. 18.

Porter, Fairfield, “Reviews and Previews,” Art News, Vol. 50, No. 7, December 1951, p. 49.

Porter Fairfield, “Reviews and Previews,’ Art News, Vol. 51, No. 4, June 1952, p. 82.

Porter, Fairfield, “Reviews and Previews,” Art News, Vol. 4

54, No. 9, January 1956, p. 56.

Russell, John. The Meanings of Modern Art. New York, New York: Harper and Row, 1974.

Soby, James Thrall, “Double Solitaire,” Saturday Review, Vol. 37, No. 32, September 1954.pp. 29-30.Exhibition Catalogs:

Catherine Viviano Gallery, Kay Sage Retrospective Exhibition, New York, 1960.

Catherine Viviano Gallery, A Tribute to Kay Sage, New York, 1960.

Catherine Viviano Gallery, Your Move, New York, 1961.

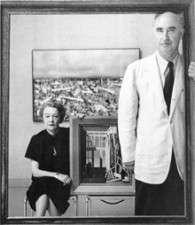

TWO OF A KIND Kay Sage and Yves Tanguy, here shot for Time magazine on the occasion of their joint exhibition at the Wadsworth Atheneum in 1954.

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Sage developed her own distinctive brand of surrealism after meeting the French artist Yves Tanguy, whom she brought back with her to the States upon the outbreak of World War II. They eventually settled in Connecticut, where they lived and worked for the remainder of their lives. Like Tanguy, Sage sought to achieve a dream-like effect through hallucinatory, airless landscapes, devoid of human inhabitants but populated by unsettling draped figures, whose humanity cannot be ascertained. Though overshadowed by her more famous husband, Sage was determined to be taken on her own terms, and in retrospect, it is now evident that Sage was as influential for Tanguy’s later work as he was in her early development. The muted palette and nearly invisible brushwork are a constant feature of Sage’s work, lending her images the illusion of having materialized without human agency.

- Highlights of American Art, 2020