Charles Marion Russell

American, 1865-1926

Where the Best of Riders Quit, 1920 ca.

bronze

14 3/4 x 8 x 8 3/8 in. (object w/o base)

SBMA, Gift of Malcolm P. Aldrich in memory of Edward S. Harkness

1966.8

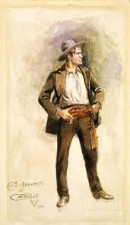

Undated photo of Charles M. Russell.

“The west is dead… you may lose a sweetheart but you won’t forget her.” - Charles M. Russell

RESEARCH PAPER

Charles M. Russell was born into a well-to-do family in Oak Hill, Missouri. His parents tried to give him a good formal education and even sent him east to military school hoping to get him to keep his mind on studying. There, he spent most of his time on guard duty for being negligent in his studies. It seems his mind was on art and the west. He would trade drawings for homework problems in math. His parents sent him to Montana for a summer visit, hoping he would be ready for school in the fall. He stayed on and for a while worked on a sheep ranch, but this was not for him. He was a cattle man; for the next 15 years, Charles worked on the range as a cowboy. It was during this time that he gathered such a backlog for his art and recollections of western life.

As the story goes, he always had a piece of clay or wax in his pocket. Many a time, he’d be talking to a friend, not looking down while modeling a wild animal or figure in his pocket or under his hat, only to pull this out to everyone’s surprise at the end of the conversation. He would then smash it down and come up in the next few minutes with another one.

He loved the free and wide open spaces; his philosophy was “live and let live”. He was very much in tune with the Indians and their philosophy of life. In fact, at one time he considered living with a small Canadian Tribe, the Blood Indians. His Indian friends had even picked a wife for him and given him the name meaning “antelope”. His experiences living with the Indians and the paintings he made of their lives are, in some cases, our only historical record of those particular tribes.

In 1893 he gave up his job as a cowboy and began living on his earnings as an artist. His commissions were quite small in the beginning, mostly due to his own choosing, which wasn’t rectified until his marriage. His wife, Nancy, demanded and got much more for his paintings. She also suggested they go to New York for a time, where they met some well-known artists. He also spent much time in California, utilizing the Hollywood market and vacationing in Santa Barbara. He knew such personalities as Marchland, Edward Borein, Will Rogers, etc. In fact, he was quite the humorist. When he and Will Rogers were around, it was Charlie’s stories of the Old West that everyone wanted to hear.

In his sculpture, one can see the emotion he is expressing. Once asked if he ever used a live model, laughing, he said, “A human model would have a hell of a time posing for me, I’d have to spike him onto a wall”. If he had difficulty forming a figure in a painting, he’d shape it out of clay and his difficulties would be ironed out. From Working from his memories, he created objects in action.

His lack of formal training was a source of pride. In fact, he ridiculed the European schools, particularly Impressionism. He had his life on the range, his honesty, humor and love of people, particularly Indian people.

Prepared for the SBMA Docent Council–L.C. VS:mf 5/1/69

Prepared/typed and edited for the web site by Rosemarie Gebhart and Lori Mohr, fall 2012

Self portrait of Russell dated 1900.

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Largely self-taught, Russell specialized in representations of the Old American West. A realist, his subjects came from direct experience as a rancher and a cowboy. He also spent time living among a tribe of the Blackfeet Nation in 1888, which specialists believe is the reason for the detailed authenticity of his depictions of Native Americans.

This is one of his best-known sculptures. His wife Nancy described it thus: “The horse is making a fight and is figuring on landing on his rider. The rider, being of the best, is thinking too. As he steps off his horse he will be standing beside him when he lands and, having ahold of the cheek piece of the hackamore, will have the horse bump his head a little harder when he hits the ground. As the horse comes up the cowpuncher will grasp the horn and be in the saddle when he gets on his feet again. Most horses think twice before they throw themself a second time.”

- Preston Morton Reinstallation, 2022