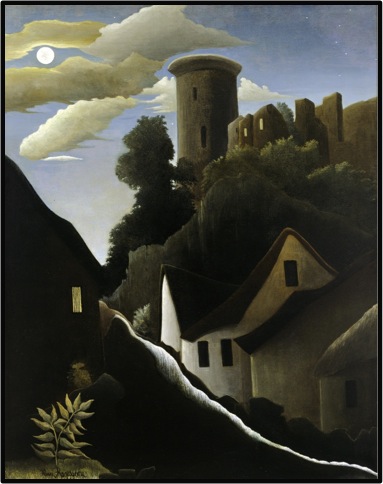

Henri Rousseau

French, 1844-1910

Castle in Moonlight (Le Donjon), 1889

oil on canvas

35 1/2 x 27 3/4 in.

SBAMA, Bequest of Wright S. Ludington

1993.1.9

Henri Rousseau, Myself Landscape Portrait, 1890, oil on canvas

RESEARCH PAPER

Le Donjon [since retitled Castle in Moonlight (Le Donjon)], is by the French artist Henri Rousseau, who painted this work in 1889. The Provenance states that Rousseau gave the painting to his baker (he was always ready to barter and a fair amount of his paintings were found after his death in the households of local traders.) It then found its way to Bela Hein and her collection in Paris. It was exhibited in Paris in 1926 and from there went to the Marie Harriman Gallery in New York City. It was frequently exhibited in the United States until it was purchased in 1942 by Wright Ludington. The painting was donated to the Santa Barbara Museum of Art in 1993.

The serene French countryside at night takes on a quality of fantasy or dreamland-muted greens, dull blacks, the quietly mysterious darkness of the trees silhouetted against the starry sky, and the flowing silvery light of the stream and its reflection on the hillside, all blend together to create this enchanting scene. The moon, clouds, and stars painted in the background give distance and add perspective to the picture. The apparent simplicity of large monochrome areas, the path of water dividing the canvas, the clouds floating in the sky are not mere accidents. Some detail has been added in the dungeon window, clouds, cottages, and plants in the bottom foreground for balance, contrasting it with huge areas of plain color. His palette makes a major contribution to the mood of this painting. It has a dream-like effect of stillness and repose. The bright light of the midnight moon adds emphasis to the stillness. It shines equally from all sides and never reduces the blackness of the shadowless trees, castle, and dungeon. Rousseau's inspiration may have been fantasy or dream. He seemed obsessed with one repeated theme, imagining a strongly lighted distance, against which he silhouetted darker forms. This same dream reappears from his first painting titled Carnival Evening to the last jungle pictures, painted toward the end of his life.

The tropical looking plant in the left foreground seems to be incorporated with his signature. "Rousseau considered that his signature was an integral part of a total painting and carefully worked out not only its position on the canvas and its size, but its color."1 (There is a peculiar smudge directly below the dungeon window. Perhaps a mistake, this part of the painting is a bit odd, and out of character.)

Henri Rousseau was born in Laval, the capital of Mayenne, in northwest France in 1844. Rousseau did poorly in school, did not graduate, but enlisted in the 52nd Infantry in 1864 and served for seven years. His first wife Clemence died after twenty years of marriage at age 36. He remarried and was given a post in the Municipal Toll Service in 1871. His poet friend Jarry gave him the affectionate nickname "Le Douanier", or Customs Inspector.

It was about 1885 when he began to paint full-time having retired on a small pension. Too poor to enroll in art school, he was entirely self-taught. He studied the flora at the Paris Conservatory, visited the zoo, and used postcards and books as his inspiration, as well as his own dreams and imagination. According to Carolyn Keay, he was the first and greatest of what we now call modern primitive or 'naive' artists. Redon, Gauguin, Lautrec, and Signac were among the first artists to admire his paintings. Gauguin admired Rousseau for his use of black at a time when black had practically been eliminated from the palette. The Impressionists used other tones of colors for dark value. His first exhibition was in 1889. Poet Alfred Jarry introduced him to the intellectual world of Paris.

At this time in the world, Perry had opened up Japan, the Franco-Prussian War had been fought in 1870-71, the Suez Canal was opened, and the Boer War between Britain and the Dutch in South Africa had started. Up until his death in 1910, the world saw the motion picture, sound recording, the beginning of aviation, Freud's psychoanalysis, Einstein's theory of relativity, the model touring car, Marconi's radio, and the camera.

At the turn of the century, Paris was alive with young artists and new stimulating ideas. The musicians were Tchaikovsky, Debussy, Georges Bizet wrote the opera Carmen, and Stravinsky composed the Rite of Spring Ballet. Picasso's early painting Les Demoiselles d'Avignon was painted in 1907 and was an example of cubism. Norwegian artist Edvard Munch, an expressionistic painter, painted The Cry, which is a study of human terror. The years 1907 to 1910 were the fullest period in Rousseau's life. At 63,he found himself in the center of the most advanced group of artists and writers in Paris, among them Max Webber, Apollinaire, Delaunay, and Jarry. He received his first large commission from Madame Delaunay for the Snake Charmer, which now hangs in the Louvre.

Rousseau's approach to painting was far from literal. Because he was untrained, he was clumsy and awkward when he painted the human form, especially the face. He also had a problem with linear perspective, but was perfectly at ease when he painted trees and vegetation. He painted still-life, landscapes, and portraits, but landscapes were the core of his work. In the late 19th Century, a keen interest in the exotic was present. Colonial expeditions and religious missions, success of writers such as Jules Verne and Pierre Loti bear witness to this trend toward the exotic. His distinctive style gained approval from Picasso, Brancusi, and Kandinsky.

In his studio, Rousseau painted in a trance-like stillness from morning to night, slowly proceeding from the top to the bottom of his canvas. A picture might take two or three months, and he was in luck if he would receive a hundred francs for it. No more than two hundred paintings and fifty drawings survive. The disappearance of these works is explained by the fact that Rousseau would exchange pictures for food and other services. His laundress in Paris and her family's farm in Amiens have discovered pictures. Many paintings once considered lost, are turning up, but with different titles. Originally Le Donjon was titled Le Chateau-Fort or Medieval Castle. Rousseau seemed to use these smaller works to barter for his livelihood. Other works that were found were The Sleeping Gypsy, discovered in the workshop of a plumber in 1923, and the painting titled War was found rolled up in the barn of a farmer in 1944.

After his second wife Rosalie died of cancer, Rousseau fell madly in love with a much younger woman. She severed relations with him and he was broken-hearted. He shot himself in the leg and the wound became gangrenous. Rousseau died alone in a Paris hospital in 1910 at the age of 66.

In his obituary, Ardengo Soffici, the Italian Futurist who had known the Douanier well, wrote: ‘What makes Henri Rousseau different from his popular fellows ... is his tendency to fantasy and especially his almost nostalgic passion for the sights and life of exotic lands ... that overflowed into many immense compositions in which the grotesque is joined to the touching, the absurd to the magnificent, and totally distorted objects to things undeniably beautiful and poetic.’2

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Janet Dal Bello, March 1994.

Footnotes

1Dora Vallier, Henri Rousseau (New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1962), p. 36.

2 Roger Shattuck, Henri Rousseau Essays (France: Galeries Nationales du Grand Plais, 1985), p. 245.

Bibliography

Cooper, Douglas. Les Editions. Paris: Braun Et Cie, 1951.

Gardner, Helen. Art Through the Ages. 4th ed. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, Inc., 1959.

Keay, Carolyn. Henri Rousseau Le Douanier. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 1976.

Larkin, David, ed. Rousseau. Italy: Random House, 1975.

Leonard, Sandra E. Henri Rousseau and Max Webber. New York: Richard Feign and Co., 1970.

Le Pichon, Yann. The World of Henri Rousseau. New York: The Viking Press, 1982.

Rich, Daniel Catton. Henri Rousseau. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1946.

Vallier, Dora. Henri Rousseau. New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1962.

Catalog

Museum of Modern Art. Henri Rousseau. France: Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais, 1985.

GUIDE BY CELL

Guide by Cell Script

Susan Lowe

When looking at Castle in Moonlight by Henri Rousseau one is initially drawn to that bright white diagonal line – is it a river or perhaps a reflection of the moonlight? The contrast between the line and the dark area surrounding it is so great here – you can almost imagine it glowing in the dark!

In this painting one can sense the signature effect Rousseau’s work often had – he is able to take a simple view of the French countryside and make it feel commonplace and strange at the same time.

Henri Rousseau was a self-taught artist and not formally trained, although he was aware of the contemporary art of his time. Nevertheless, he was a skilled painter as his detailed brushstrokes and coherent compositions such as Castle in Moonlight show.

Note his meticulous painting style. No brushstrokes are seen. This landscape does not exist in real life. It is a fairytale fantasy of rich, complex design. With his use of light and dark, he achieves a specific atmosphere and mood, a sensation of the evening’s colors.

Let your eyes follow the buildings to the right of the white line – up to the castle – to the moon and back down again, All the light from the painting appears to come from the moon itself – the shapes and forms in front are seen in silhouette.

Again, the images are not intended to be fully realistic – they do have some gradation of color that adds depth – but they can also be seen as flattened overlapping layers of different dark and light geometric forms: triangles, squares, rectangles, circles and cones, all arranged in striking diagonals.

But what is happening in the lower left corner of the painting? Rousseau always included his signature in a painting in a specific way, surrounded by Palm Leaves. But this signature is not randomly placed – it is an integral part of the composition. With your hand in front of you – try to block out the signature - note what happens when its eliminated – the composition changes!

It has been said of Rousseau that it is fortunate that he did not receive formal artistic training – as he would have been told what to do and what not to do. There were rules, but he did not care about those rules – he made his own.

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Henri “Le Douanier” Rousseau (so nicknamed because he originally made his living as a customs official) was a self-taught artist whose voracious borrowings from popular culture and naïve, simple style were key influences on the development of Cubism. This fantastical image of an abandoned castle silhouetted against the night sky, typical of his work, is characterized by the simplified, hard-edged modeling of forms that Picasso and Braque would adopt in their own early Cubist paintings.

The castle depicted here is based on an actual location – the château of Falaise, in Normandy. Rousseau did not paint it from life; as was his usual practice, he probably worked from a photograph or a guidebook illustration. The lack of direct observation allowed him to introduce tantalizing ambiguities into the composition. The pale diagonal at lower center could be either a path, the top of a wall or moonlight shining on a hillside. The cottages in the foreground appear disproportionately large in comparison to the castle above, and a twinkling constellation appears to shine too brightly in a blue sky cushioned by clouds. In doing so, he transformed a tourist cliché into a mysterious, poetic and faintly menacing image.

- Ridley-Tree Reinstallation, 2022