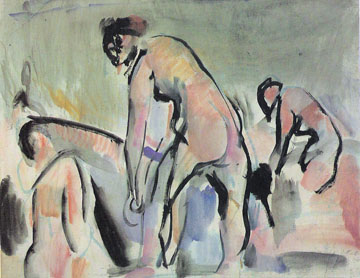

Georges Rouault

French, 1871-1958

The Bathers, 1908

watercolor on paper mounted on canvas

19 x 24 1/8 in.

SBMA, Bequest of Dr. MacKinley Helm

1963.33

Original lithograph worked with chalk, brush and scraper in black ink. 1925. Signed in the stone. From the issued edition of 385 impressions for the series 'Souvenirs Intimes - Intimate Memories'. (There were also 60 signed proof impressions). Drawn and printed at the studio of Duchatel, Paris 1925. Issued by Frapier, 1925.

RESEARCH PAPER

Georges Rouault’s 1908 Bathers is watercolor on laid paper, donated to S.B.M.A. by Dr. MacKinley Helm in 1963. From November 1940 till March 1941, Dr. and Mrs. MacKinley Helm of Boston lent the Bathers to the Retrospective Loan Exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, Boston, where it was displayed with other works under the grouping title of: “The Passing Scene: Compositions".

Bathers have appeared in Rouault's oeuvre since 1903. From 1906 until 1916, he used the theme frequently. Rouault's predilection during the years 1902-1914 for watercolor, allowed him rapidity in execution creating the "pulsatory" images to vibrate. From 1918-1930, he gave up watercolor and gouache in favor of painting in oils.

Our painting was executed three years after the exhibition marking the emergence of Fauvism, and after Cezanne's completion in 1905 of the “Grandes Baigneuses” on which he had worked seven years. In it, Cezanne re-introduced line and clearly delineated broad strokes of color. Superimposed one upon the other, these clearly articulated color shapes left a perceptible record as one brushstroke overlapped another. From Cezanne, Rouault learned to leave spots in reserve to highlight more effectively the rest of the drawing; and to construct a form through the use of color, without rejecting a thick, rapid outline to describe form. Rouault's study of Cezanne's most famous work: The Bathers at Rest encouraged him to render form boldly and impressed on him the need for coherent unity of pictoral elements above and beyond any reference to visual reality. His concept of space changed accordingly: his figures came to occupy a limitless, self-contained, imaginary space rather than being enclosed in space.

Though influencedby the Fauvesand Matisse, Rouault’s expressionism is an isolated phenomenon that stands on its own. Born on May 27, 1871, in Versailles, Rouault spent his early youth studying and working in the atelier of his cabinetmaker father; and later at L’Ecole des Beaux-Arts. He also worked as a picture restorer and stained-glass maker and had a great admiration for medieval stained-glass windows. The artists who influenced him were Gustave Moreau, Leon Bloy, Ambroise Vollard, Andre Suares, Rembrandt, Goya, Daumier, Cezanne, Grunewald, Watteau, and Corot. From his work as an apprentice glassworker, Rouault developed his use of enveloping line and color. In his art, there is a vital unity between poetry and craftsmanship. He is determined to have his paintings affirm themselves only as paintings. That is why the concern for the contour haunts Rouault as strongly as it did Cezanne. “Le contour me fuit” (The contour escapes me) he said,1 and he adds: “ce mot lapidaire resume toute la epinture et va bien au dela” ( this lapidary word summarizes all painting and goes far beyond).2

The thick black contours have an essentially pictorial value: They perform the artistic function of bringing out the color by contrast. The Bathers’ image is asserted through the strength of Rouault's line, the luminosity of his color, the brush strokes. The drawing consists of nervous lines the stretch, and dash across the paper, tracing, with a sure stroke, contours that describe and recapitulate the form, and are supplying the work with rhythm, cadence, and a decorative quality. He uses black, obtained quite often with ink, and blue is the dominant hue.

Rouault has long focused his attention on figures rather than composition; in the Bathers some elaboration of the latter had been required in order to situate a figure group. It is to the combination of composition, lines, and color that the picture owes its esthetic value. Rouault created for himself conditions of imaginative freedom in the handling of form. His simplification of form follows the dictates of sentiment rather than Expressionist style. It is that depth of feeling that simplifies Rouault’s space composition. The images are closely related but the lack of actual space makes the physical relation uncontrollable. Space is only a suggestion of the imagination. His form and, his color which is his form, is independent of nature. It is a creation parallel to nature’s creation. “Form and color – this is our language”, declared Rouault, who mistrusted words and the explanations of critics.3

In 1898, Rouault painted some landscapes in the open air and so learned to relate the volume of objects to the general effect of light and shadow. His interrelated figures stand out as powerful volumes against a bare ground and are further enhanced because no foreground has been interposed that would unnecessarily distance them from the viewer. They affirm their presence in decorative and purely plastic terms. Rouault's faces are anonymous on the contrary of Toulouse-Lautrec's which are profoundly individual.

Rouault' s compositional method, in its sobriety, the architecture of the work rests on a central element well balanced on the left and on the right by two symmetrical, equivalent masses, impressive but uncomplicated. There is a sense of monumentality in this composition. The two figures on both sides are a little smaller but rhyme with the principal figure and their reduced scale serves to augment the grandeur of the latter. The white interstices remaining between adjoiningbrushstrokes of overlapping tender pale colors of orage, pink and grey give motion to the figures. It is a pleasant sight, an inviting one in harmony with nature.

Rouault’s art is “the expression of free imagination deeply rooted in sentiment” (Lionello Venturi’s introduction). Rouault’s idea of art was quite simple and clearly outlined within the true domain of painting – in terms of “form, color, and harmony”. Rouault was the most individual of the great painters in the last century. His is a popular art because it is one that is generalizing in the extreme. It is an art were genuiness and sincerity triumph.

Jacques Maritain. Georges Rouault. New York, Abrams, 1954, p.4.

Giuseppe Marchiori. Georges Rouault 1871-1958. New York: Reynal, 1967

Bibliography

Courthion, Pierre. Georges Rouault. Including a catalogue of works prepared with the collaboration of Isabelle Rouault. New York: Abrams, 1962.

Dorival, Bernard. Rouault. Naefels, Switzerland. Bonfini Press Corporation. 1983. Translation by Garry Apgar, 1984.

Marchiori, Giuseppe. Georges Rouault 1871-1958. New York: Reynal, 1967.

Maritain, Jacques. Georges Rouault. With notes on Rouault’s prints by William S. Lieberman. New York: Harry N. Abrams Inc. and Pocket Books, Inc., 1954.

Venturi, Lionello. Rouault, Biographical and Critical Study. Translated by James Emmons. Paris: Skira, 1959.

Bulletin 19/1972. The National Gallery of Canada. Cezanne, Vollard, and Lithography: The Ottawa Maquette for the “Large Bathers”. Color Lithography by Douglas W. Druick.

European Drawings in the collection of the Santa Barbara Museum of Art. Alfred Moir, Editor.

Museum of Modern Art, Boston, “Rouault. Retrospective Loan Exhibition”, November 1940 – March 1941.

Pasadena Art Museum and the Ward Ritchie, “Cezanne Watercolors”, Johns Coplans, Los Angeles, 1967.

Great Paintings from the Pushkin Museum, Moscow. Text by K. M. Malitskaya, Curator of Western European Art. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. New York: Publishers, 1964.

Prerared for the SBMA Docent Council by Jehanne Brown, 1991

Prepared for web site by Loree Gold October of 2005