Georges Rickey

American, 1907-2002

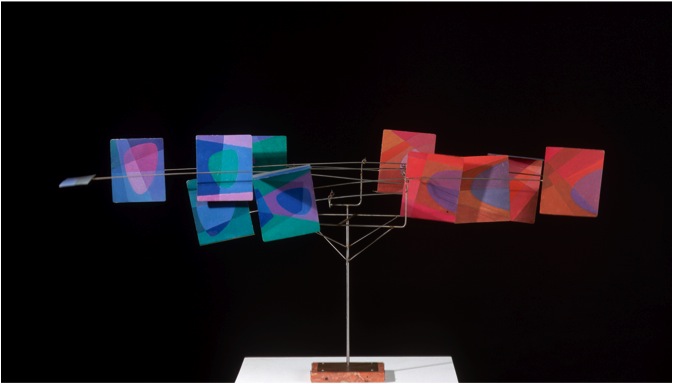

Diptych: The Seasons I, 1956

stainless steel and polychrome

17”x 38 x 13 in.

SBMA, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Warren Tremaine

1955.53

“Motion itself as a component of expressive art is not new to our time: we have had dancers for thousands of years and, since the sixteenth century, several attempts at mechanized choreography—clocks, fountains, and all manner of toys have used motion as an aesthetic component. Yet these were considered to be remote from sculpture and to be lesser arts. The last half of the century has seen a great change. Quiet masses of stone, wood, and bronze are now known to be enormously copious energy and their apparently solid material to be as spacious as the firmament. New conceptions of matter and the new relevance of motion quite naturally condition contemporary art. So called ‘space sculpture’ and kinetic designs no longer seem remote from the ideas which produced solid or still sculpture.” - George Rickey, from “Kinetic Art—A Summary,” Louisiana—Revy, 1961. FN 1

RESEARCH PAPER

“Diptych—The Seasons I,” was created by sculptor George Rickey in 1956, of stainless steel and polychrome paint. The donors of the sculpture, Mr. and Mrs. Warren Tremaine, were influential patrons of Santa Barbara’s artistic community. Kit Tremaine, originally from the Southeast, became a well-known benefactress of the arts and was actively involved with the Santa Barbara Museum of Art and its Board of Trustees.

The Santa Barbara Museum of Art’s “Diptych—The Seasons I” is one of several versions sculpted by George Rickey and is quite similar to a work that remains in the collection of the artist. Both works are titled “Diptych—The Seasons ,” and were produced in 1956. Although some authors describe the diptychs as “early” in terms of their chronological position in Mr. Rickey’s overall body of work, both diptychs are fairly representative of the artist’s sculptural style, use of materials, and technique. It is important to note that whether a Rickey sculpture is small—as are the diptychs—or large, such as SBMA’s “Two Planes Vertical-Horizontal II” (1970), the underlying concept remains the same: a Rickey sculpture is a delicate and complex choreography of movement.

George Warren Rickey was born in South Bend, Indiana on June 6, 1907. His father was a mechanical engineer employed by the Singer Company as manager of their sewing machine factory. Rickey’s mother—the daughter of a New York Supreme Court judge and a drawing teacher—was one of the early graduates of Smith College. In 1913, George’s father was transferred to the company’s Scotland branch, and the young boy stayed with his paternal grandfather, a clock maker in Athol, Massachusetts, for several influential months before joining the family in Scotland. George and his five sisters won many drawing contests while attending school in Scotland, but George seems to have been more inclined to pursue his academic and mechanical interests at this time in his life. During holidays, from about the age of nine until he left for college, George sailed his family’s 38-foot boat along the coastal waterways of western Scotland, mastering the mechanics of sailing even as he gained an understanding of wind currents and the laws of motion, both concepts which would become central to Rickey’s sculpture. Later, in an article about kinetic sculpture and its potential, he would describe the few simple, basic movements that exist, comparing them to “the classic movements of the ship—pitch, roll, yaw, sheer, forward, backward, up and down, sideways as in keeled sailing vessels…”FN 2

After attending a Scottish boarding school, Rickey read Modern History at Balliol College, Oxford, despite his family’s expectations that he would study engineering at MIT, as his father had. George was able to study drawing at the Ruskin School while at Oxford, and went on to study painting in Paris. For approximately two intensive decades, Ricky’s life seems to have been comprised of equal measures of painting, teaching, studying and writing, until after World War II, at age thirty-seven, he created his first sculpture. Interestingly, Rickey’s service in the Army Air Corps (1942-45) seems to have had a profound impact on his career as an artist. Due to his long-dormant mechanical abilities having been revealed through army tests, Rickey was assigned technical work which required that he understand the effects of wind and gravity on ballistics. During this time, Rickey produced a few mobiles in the army machine shop, none of which survives. A few years later, Rickey experimented with glass chimes and mobiles (again, a fragile medium, and only two survive), then progressed to mobiles of plastic, brass, copper, and/or painted steel elements, using a mechanical system called a catenary which had been used on and off since 1932 by Alexander Calder. Although Rickey was clearly influenced by Alexander Calder, one distinction between their work was that Rickey did not use the organic shapes preferred by Calder, leaning toward more geometric and abstract elements. Another difference between the artists was Rickey’s attempt to “build a certain quality of imponderability into the system of motion that he uses.” FN3 In other words, Rickey’s objective was to obscure the mechanical activity of his sculptures to prevent the viewer from being able to predict one movement based upon a previous movement. This invites the viewer’s contemplation of an object over a period of time, adding another element – time - to Ricky’s choreography of forms in motion.

After a summer visit to Calder’s studio in 1951, Rickey produced a sculpture which anticipated future developments in his art. “Silver Plume II” was large, it was made entirely of stainless steel, it was intended as outdoor sculpture; and it was built to move with more freedom than any of Rickey’s previous works. The sculptor accomplished this by building his first universal joint; so that the sculpture could bob up and down, as well as move from side to side. Rickey moved farther away from Calder’s art as he continued to search for a mechanical system which was not readily legible to the viewer at a glance: by veering away from Calder’s method of linking parts. Rickey was able to achieve a smoother, more fluid, and less predictable system of movements. His goal was to make his sculpture responsive to even the slightest movement of the air around it, necessitating a highly developed technical approach. The effect of Rickey’s sculpture has been described by Nan Rosenthal, his biographer, as a “smooth randomness” operating “within an overriding order.” Rosenthal continues: “Such movement seems suitable for articulating both the vast cycles and indifference to man we associate with the mineral and vegetable aspects of nature: storms, seasons, constellations, the rustling of leaves, the scattering of atoms in a bubble chamber. Rickey gives voice to these patterns of nature with forms that are fully abstract.” FN 4 The foregoing descriptions are particularly applicable to SBMA’s “Diptych—The Seasons I.” Its planar forms are painted with bright colors, suggesting certain times of the year. Contrasting colors are paired with contrasting shapes: cool versus warm, curves versus angles. The painted surfaces are reminiscent of sails , or blades, or rudders, and contrast with the metallic structure, just as the weightiness we associate with metal contrasts with the airy lightness of the movement of the forms. The cyclical nature of the seasons—implied through color and the title of the sculpture—is belied by the gentle randomness of the motion, which can become so slight as to be barely perceptible. The system which Rickey employed in this movemented sculpture is pendular, although the elements do not look like pendula at all. By carefully adjusting the weights and bearings so that there is no definitive state of rest, the artist conveys a mild tension, a pleasurable suspense, as we wait for the unpredictable movement to resume. Rickey conceived of the diptych as a kinetic painting - a painting in motion - and one can see how his early work as a painter would have combined with his interest in three-dimensional movement to produce this sculptural form.

From 1957 onward, Rickey continued to develop and refine his art. He began to work on a larger scale, which impacted the smaller works he continued to produce. He began to use stainless steel almost exclusively and discontinued his polychrome work on other metals. Perhaps most importantly the forms which Rickey used became less representational. Rickey’s writings during this period began to be widely published, paving the way for the acceptance of Kinetic Sculpture, of which Rickey had become a strong proponent. In 1964, at an exhibition called Documents III in Kassel, Germany, George Rickey established himself as one of the foremost kinetic sculptors in the world. Rickey’s “Two Lines” stood thirty-five feet tell, reflecting the moon’s pale light as tapering blades of steel languidly swung above the heads of the assembled throng. When, the next year, the Museum of Modern Art in New York purchased one of Rickey’s large sculptures for its collection, his reputation was assured.

Rickey was decades older than many of the artists in the vanguard of the kinetic sculpture movement, which has been referred to as “the movement movement.” Yet there was, and is, an even more fundamental difference in Rickey’s approach which makes his art unique among kinetic sculptors. Ricky does not choose to use the electric motors which are generally responsible for the motion in kinetic sculpture. Instead, Rickey’s sculptures are set into motion by currents of air or the touch of a hand.

Rickey began to collect Kinetic Sculpture during the 1960s, amassing approximately one hundred works by other kinetic artists, as well as influential Constructivists such as Gabo FN 6 and Malevich. Rickey’s sculpture collection and his writings during the same period reflect the artist’s openness to the work of others, as well as an abiding theoretical and scholarly interest in his discipline. However, Rickey’s own expressive purposes are not revealed through either his writings or his habits as a collector. In a sense, despite countless words, spoken and written, the inner mechanism of George Rickey eludes us in the same way that he has chosen to make the mechanics of his sculpture elusive and imponderable.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Deanna McHugh. April 6, 2000.

Website preparer: Judy Seborg. January 27, 2004.

Please also see the video of Diana DuPont’s March 1, 2000, interview with George Rickey.

Footnotes:

I From George Rickey/Kinetic Sculptures. Exhibition Catalogue, Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston,

March 14-April 26, 1964.

2 George Rickey, “The Morphology of Movement” The Art Journal (New York) Summer 1963, p. 226.

3 Rosenthal, Nan. George Rickey. Harry N. Abrams, New York City, 1977, p. 32.

4 ibid. p.36

5 Hilary Dole Klein, “George Rickey: Dancing on the Wind,” Santa Barbara Magazine, January/February, 1990,

p. 47

6 To whom Rickey dedicated his book, Constructivism: Origins and Evolution, Geroge Braziller, Inc., New York,

1967. See p. v.

Bibliography:

Klein, Hilary Dole. “George Rickey: Dancing on the Wind,” Santa Barbara Magazine, January/February, 1990.

Rickey, George. Constructivism: Origins and Evolution, George Braziller, Inc., New York, 1967.

George Rickey/Kinetic Sculptures. Exhibition catalogue, Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, March 14-April 26, 1964.

Rosenthal, Nan. George Rickey. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York. 1977.

POSTSCRIPT

New York Times

July 21, 2002, Sunday

METROPOLITAN DESK

George Rickey, Sculptor Whose Works Moved, Dies at 95

By KEN JOHNSON ( Obituary (Obit); Biography ) 777 words

George Rickey, a sculptor widely known for his abstract kinetic sculptures, died on Wednesday at his home in St. Paul, Minn. He was 95.

Mr. Rickey was one of two major 20th-century artists to make movement a central interest in sculpture. Alexander Calder, whose mobiles Mr. Rickey encountered in the 1930's, was the other. After starting out as a painter, Mr. Rickey began to produce sculptures with moving parts in the early 50's, but it was not until a decade later that he achieved the kind of simplicity and scale that would make him an important figure in contemporary art. At that point, he began to produce tall stainless-steel sculptures with long, spearlike arms attached to central posts. Rotating on precision bearings devised by the artist, the arms were balanced so that slight breezes would cause them to sweep like giant scissor blades, tracing graceful arcs or circles against the sky. In the ensuing years, Mr. Rickey set in motion all kinds of geometric configurations -- wavering stacks or grids of flat squares, shifting open rectangles, zigzagging beams, spinning shell-like forms. His work was often compared with Calder's, but while Calder's abstract mobiles had playful, organic qualities related to Surrealism, Mr. Rickey's geometric forms and machinelike engineering harked back to Constructivism. That was the early-20th-century Russian movement about which Mr. Rickey wrote a scholarly book (''Constructivism: Origins and Evolution,'' George Barziller, 1967).

His work was also in step with new sculpture trends toward abstract simplification. Unlike the Minimalists, however, whose elementary structures tended to bore or mystify many viewers, the fascinating movements of Mr. Rickey's sculptures appealed to a wide audience, and he received commissions from all over the world to create public works.

Mr. Rickey was born on June 6, 1907, in South Bend, Ind. In 1913 the family moved to Scotland, where his father, an engineer for the Singer Sewing Machine Company, had been transferred. While studying modern history at Oxford, Mr. Rickey also took courses in painting and drawing at the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art. After graduation, he went to Paris to study art at the Académie Lhote and at the Académie Moderne, where he worked under the Modernist painters Fernand Léger and Amédée Ozenfant.

After teaching history briefly at Groton School in Massachusetts, Mr. Rickey devoted himself to painting full time. He had his first solo exhibition at the Caz-Delbo Gallery in New York in 1933, and a year later he moved to New York and set up a studio. His early paintings reflected the influences of Cézanne and Social Realism. During the late 30's, Mr. Rickey taught art at several schools, including Olivet College and Kalamazoo College in Michigan, Knox College in Illinois and Muhlenberg College in Pennsylvania.

Mr. Rickey served in the Army Air Corps in World War II. He was assigned to work with engineers in a machine shop to improve aircraft weaponry, an experience that reawakened earlier interests in science and technology. After the war, he resumed his peripatetic teaching career. A year studying Bauhaus teaching methods at the Chicago Institute of Design in the late 1940's was decisive, for it was there that he seriously began to consider the idea of bringing together geometric form and movement. In 1949, while working as an associate professor at Indiana University, he made his first kinetic sculpture using window glass.

In 1960 Mr. Rickey moved to East Chatham, N.Y., which remained his home base until the end of his life. He retired from teaching in 1966 after five years at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, N.Y., but continued to make sculpture and to travel incessantly. To keep up with his public commissions and exhibitions, he maintained studios in Berlin and in Santa Barbara, Calif. His last sculpture -- his tallest, at 57 feet 1 inch -- was installed at the Hyogo Museum in Japan on March 30.

Mr. Rickey's wife, the former Edith Leighton, whom he married in 1947, died in 1995. He is survived by his sons, Philip, of St. Paul, Minn., and Stuart, of San Francisco.

It is a curious fact of contemporary art history that Mr. Rickey left no significant artistic heirs. Perhaps because movement in art is now found mainly on video screens, no sculptor has adopted his innovations with comparably persuasive ambition or elegance.