Frederic Remington

American, 1861-1909

The Mountain Man, 1903 ca.

bronze

28 5/8 x 11 x 12 1/2 in.

SBMA, Gift of Mrs. Charles A. Smolt in memory of Malcolm McNaghton

1962.40

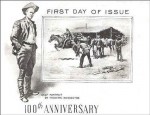

USA 1961. Cachet from a First Day Cover commemorating the centennial of Frederic Remington. The cachet shows a self-portrait and a black/white reproduction of Remington's painting "Coming and Going of the Pony Express".

"I knew the wild riders and the vacant land were about to vanish forever... and the more I considered the subject, the bigger the forever loomed. Without knowing how to do it, I began to record some facts around me, and the more I looked the more the panorama unfolded." - Frederic Remington

RESEARCH PAPER

Description

The Mountain Man is a bronze sculpture with a dark green to black patina of a mountaineer on horseback descending a treacherously steep, rough, uneven path. Because Remington wanted to emphasize the high steep slope of the path, the 28” high sculpture is several inches higher than his other bronzes. The strong diagonal produces an abrupt downward movement. Remington captures a moment of time in bronze and makes time stand still. The sculpture which can (and should) be viewed from many angles was originally worked in a waxy preparation called plastine and then cast via the “lost wax” (cire perdue) method of bronze casting. (see below for detailed account of his casting method.)

The Mountain Man, one of the intrepid thousand or so who hunted the beaver and fought the Indians in the Rockies, paved the way and provided guides for the westward expansion of the United States. The sack around his neck held his few personal belongings, the Green River skinning knife at his belt made his living, and the Hawken rifle in his hand was his passport to the great frontier. Remington said of this subject: “The Mountain Man I intend as one of those old Iroquois trappers who followed the fur companies in the Rocky Mountains in the ‘30’s and the ‘40’s.” (1830 and 1840) It is a masterly depiction of balance, surefootedness, and accurate detailing of costume.

Remington’s work has received critical acclaim and has been described as: authentic, detailed, the work of a man who knew the West as few men have known it, action-packed, and a whirlwind of movement with a sharpness of vision. And it has been panned and described as: dehumanized and sterilized, lacking juice, depicting action but no emotion.

Relate work to period in which it was done:

A demand for sculpture in America was accelerated after the Civil War by the requirements of monument committees bent on erecting memorial statues to Civil War heroes. Remington was the first American sculptor to portray horse and rider in a realistic context, capturing the excitement, action, and drama of a frozen moment in time. He rejected the stiff rigidity of the Neo-classical equestrian monument and sculpted dynamic pieces conveying realistic action.

Medium-Technique

Advantages of Bronze

1. Bronze, 90% copper and 10% tin is a versatile and adaptable metal of high tensile strength, which makes it possible to extend form freely in any direction – arms, legs, or, as in Remington’s case, quirts, guns, and reins.

2. Bronze captures the tiniest detail. In the casting, molten metal is poured into every corner and crevice of the mold.

3. Bronze produces a wide variety of surface – smooth polished surfaces may be contrasted with sharp, clean edges – and contrasts of texture.

4. Permanence – Bronze is the most permanent of all art forms.

5. Multiple images can be made. Authentic casts of the Mountain Man have been located upward of number 74. Few casts were made during Remington’s lifetime. Models and molds were destroyed in 1919 and no “authorized” recast editions have been made. Numerous spurious casts are known to have been produced.

Cire Perdue or the Lost Wax Process as it is used in Remington’s Work

Remington was one of the first American sculptors to use the method. He wanted his work to come out flawlessly: the Lost Wax method produces more finely detailed work than the previously used French sand casting method.

1. The original figure is worked in plastine, a waxy preparation.

2. A plaster cast is made from the plastine. (in doing so, the “original” is destroyed)

3. From this plaster cast, a set of mold sections is made in glue or gelatin.

4. A plaster cast is taken of each mold piece. In doing so, the molds are destroyed.)

5. Hot wax is brushed on to the inside of the plaster cast to a thickness that the bronze will subsequently take in the final casting. The wax impression is removed when cooled.

6. Another replica of the original plastine model is made – this time in hollow wax. The artist can make subtle small changes at this point.

7. Into an opening in the wax model is poured a substance that will fill every nook and cranny of the hollow image and harden there.

8. Around the outside of the wax model is poured the easily flowing material which follows all the curves and hollows just as it did on the inside.

9. Another layer of heat-resisting substance is put on top and the whole is now a shapeless mass that suggests nothing of the delicate wax shell within.

10. The “shapeless mass” is placed in an oven and the wax melts out. (Viola! “Lost wax!”)

11. The mold is carefully baked in a sunken sand pit.

12. The molten liquid bronze is poured in.

13. The mold is allowed to cool. The now disintegrated matrix is removed and the bronze is before us – ready to have unwanted pieces filed and cut away, to have the gold color of the metal toned by chemicals, and to have appurtenances added (a bridle, a quirt, a rein) – and the bronze is completed. (Whew!)

Biographical Data

Frederic Remington, born in upstate New York in 1861, the year the Civil War began, and achieving an imposing adult weight of more than 300 pounds, was an unlikely “cowboy.” However, his love of the West developed early and continued throughout his life. To accurately depict the West, he spent two years living the strenuous life of its inhabitants: he accompanied military campaigns, prospected for gold, worked as a cowboy, and tried his hand as a sheep rancher. He became an expert rider and carefully studied horses in motion. Although he returned East to marry, live, and work, he spent nearly three months of each year traveling and observing in the West. In his own works, “I knew the wild riders and vacant land were about to vanish forever…….I saw the living breathing end of three American centuries of smoke and dust and sweat.” 2 And so he faithfully recorded the Western experience, and he did so prodigiously, producing some 2700 paintings and drawings and 23-25 bronzes – as well as illustrating 142 books and contributing to more than 40 magazines!

Remington’s life story is a “rags to riches” saga. He arrived in New York in 1885 with $3 in his pocket. Five years later, at age 29, he could afford to purchase a New Rochelle mansion. His big break had come in 1886 when he sold a cover illustration to Harper’s Weekly.

Remington turned to sculpture in 1895 at his friends’ urging. Sculptural technique came naturally to him – his in-depth study of musculature and his ability to model forms had already given a three-dimensional quality to his paintings.

Written by Faith Henkin, March, 1985

Prepared for Web Site by Terri Pagels, February, 2004

POSTSCRIPT

Although Remington was a bad student, he was accepted at Yale and was one of only two students in the newly founded art school. The other student was Poultney Bigelow, who, years later as the editor of the then important magazine Outing, was delighted to discover on his desk some pictures that were, in his words, "the real thing, the unspoiled native genius dealing with Mexican ponies, cowboys, cactus, lariats, and sombreros." It was only after he read the signature that he discovered he had studied with the artist at Yale and had failed, at the time, to recognize his genius. It was Bigelow who gave Remington his first break as a commercial artist.

Undated photo of Remington smoking, taken by Davis and Sanford in NYC.

COMMENTS

From the earliest drawings, he showed galloping horses with all four feet off the ground, a practice that won him the ridicule of critics who insisted that a horse always had at least one foot on the ground. It was not till high-speed photography froze galloping horses in mid-step that the world discovered the young boy had seen truer than the most experienced horsemen of his day, for the horse can indeed be caught with all four feet off the ground.

His love of the West was mirrored in his paintings and sculptures, which paralleled the nation's fascination with the closing of the American frontier.

- Loree Gold, 2012

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Remington identified the fast vanishing frontier life of the Western United States as his artistic subject by the time he was a teenager. Steadfast in his determination to become famous as the chronicler of the West, he went on an extended trip throughout New Mexico, Arizona, northern Texas, and back to Kansas, collecting artistic fodder for his imagery. In 1886, he sold his first cover illustration to Harper’s magazine. From then on, he enjoyed steady demand for his paintings, drawings, and bronzes of Western subjects such as this: a fur trapper working in concert with his horse to expertly negotiate the steepest of inclines. As a sculptor, Remington was known for his exacting detail, as evident` in the figure’s fur cap, fringed buckskin jacket, and his steed’s textured coat, mane, and tail. The popularity of these works made Remington wealthy enough to purchase a mansion in New Rochelle by the time he was just twenty-nine.

- Preston Morton Reinstallation, 2022