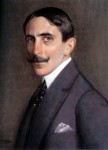

Alfredo Ramos Martinez

Mexican, 1871-1946 (active USA, France)

Monjas ante la crucifixión, 1942 ca.

charcoal on paper

31 x 30 in.

SBMA, Anonymous Donor

2000.158

RESEARCH PAPER

Alfredo Ramos Martinez has been called the "Father of the art renaissance in Mexico." His murals are well-known. He was the teacher of the great Mexican muralists, Diego Rivera, Jose Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros.

He was born in Monterrey, Mexico on November 12, 1871, the ninth child of Luisa Martinez and Jacobo Ramos. He showed artistic talent early in his childhood and was always encouraged by his parents. When his merchant father would go on buying trips for his business, he would ask his children what gifts he could bring back for them. The young Ramos Martinez would always request "colors". He especially loved the orange trees around his home and he has said that their beauty inspired him to love nature especially as the natural surroundings of his native, majestic, mountains. He sat by the hour looking at a tree, its outstretched branches green and glossy against the whitewashed, adobe wall. He won art awards and a scholarship to the Academia Nacional de Bellas Artes, Mexico City, but was uncomfortable with the strict art teaching methods at the school. He would not show up for instruction for he was developing his own methods. He had good fortune at the age of 17 years. Phoebe Hearst, the wealthy mother of William Randolph Hearst, while visiting in Mexico, admired the young artist's work. In 1897 Mrs. Hearst offered to pay his expenses for study in Europe, where he spent eleven years successfully mastering post-impressionism. Some of his best sketches from this period are on newspaper. When he was visiting Brittany in preparation for the Salon, he ran out of sketch paper so he resorted to what was at hand; newspaper. He enjoyed the use of newspaper as a support for tempera painting, because he found that it had the same quality as fresco-the paper absorbed the paint and produced an effect similar to that of a wall. He had been in Paris six years when his painting "La Primavera", 1905 was awarded the first prize in the "Salon". With this recognition he was able to support himself through his art and work. During this period he was sought after for his pastel portraits. He was close friends of Picasso, Monet, Rodin and the revolutionary poet Reuben Dario, of Nicaragua.

Ramos Martinez returned to Mexico in 1910 when Mexico was in the midst of revolution and the Academia Nacional de Belles Artes, or National School of Fine Arts, was in need of a Director. Ramos Martinez accepted the position and in 1913 also founded his Escuela de Pintura al Aire Libre (Open Air School of Painting). He was an innovator of artistic instruction. He gave his students from various backgrounds, mostly poor peasants, the freedom to experiment with various methods and their own inner creativity. For over a century the National School of Fine Arts had adopted European perspective and had taught that good things came from the Old World. He decided to direct the students towards that which was Mexican. His teachings broke away from the European prototypes and art influence and shifted towards Mexican identification with the earth and the people. When Ramos returned from his years of painting in Europe he suddenly realized how much he loved the simplicity of the Indian culture and he changed his impressionistic art skills and became sensitive to the indigenous culture and how it was threatened with extinction. He concentrated on primitive Mexican Indian themes. He felt that the shaping of clay and decorating of it by the Indians was as great in its artistic honesty as Michelangelo and Titian. He believed that his people were all love, all spontaneity, in their art. The revolution against the Mexican dictator, Porfirio Diaz in 1910 encouraged new artistic as well as ethnic independence. It became expressed as revolutionary art and murals forms. Ramos Martinez was a contributor to the Mexican Renaissance. Ramos Martinez was a gentle counterpoint to the more dramatic art of his former students Rivera, Orozco and Siqueiros, whose work addressed social and political themes and inequities.

Ramos Martinez in California

In 1929 Ramos Martinez came to the United States to find a cure for his infant daughter's bone disease. The treatment turned out to be successful. Maria Sodi de Ramos Martinez grew up to be a graduate of U.C.L.A. with a doctorate in chemistry; she is married and lives in Los Angeles. According to his daughter, "The distinguishing trait in the character of Alfredo Ramos Martinez was his enthusiasm: his optimism that when a seed is sown one already perceives the growing plant, even to the point of gathering the ripened fruit. With this unswerving and fervent faith he brought his students to triumph." He was a religious man and he felt very thankful to God for his daughter's health. There was an extraordinary shift in his aesthetic vision. His work became abruptly modern. His work was being exhibited in Santa Barbara at the Faulkner Memorial Art Gallery in 1934. He received a commission to do the murals in the Santa Barbara Cemetery chapel by the widow of architect, George Washington Smith, and Henry Eichheim, a violinist/composer. It is a marvel of simplicity. The fresco is centered on a panel showing God, the Resurrection and the Life. On one of the side panel it shows a procession of monks and nuns. Another panel shows angels and one shows a group of large heads entitled: Suffering Humanity. The figures show the native Aztec and Mayan influence. A few of the community members objected to the rendering and even went so far as to request its removal.

It is a very dramatic and reverent mural with the message of faith and hope. It has spiritual content and creative integrity. The series of murals were an expression of love of his art and of God. This led to more commissions such as public murals in La Jolla and Los Angeles. In 1946 he began his most ambitious work; a mural over 100 feet on a wall in a garden at Scripps College in Claremont, California. He died of a heart attack on November 8, 1946, leaving the mural unfinished. The J. Paul Getty Museum and a private conservator worked together to conserve the masterpiece.

Two Women Before the Crucifixion

This work is drawn using charcoal and red conte crayon on light tan paper. Charcoal is burned sticks of wood, usually a vine wood heated in a kiln until it is just carbon. The charcoal allowed him to draw lines which are thick or thin, light or dark. Red conte crayon is a fine textured stick medium. It is named after Nicholas-Jacques Conte (1755-1805), the French scientist who invented it. The crayon is a mixture of compressed pigments and a slightly greasy binder. It produces a sharp line and blends shades more softly than a wax or grease crayon.

In Two Women Before the Crucifixion , the two women appear to be nuns, as illustrated in the chapel murals at the Santa Barbara Cemetery. There are several references in the gospels to women present at the crucifixion. They can be found in Matthew, Mark and John. John 19:25, for example, says "Meanwhile near the cross on which Jesus hung, his mother was standing with her sister, Mary wife of Clopas, and Mary of Magdala."

The women's eyes are partially closed and their mouths slightly open. This is reminiscent of some Mayan statuary. Their faces appear solemn and almost gaunt. Christ is seen from the side and his head is bent forward at a sharp angle. The viewer is witness to one arm outstretched. The limp body appears lifeless.

The crucified figure of Christ is much smaller in size than the women. A lighter pressure on the charcoal gives a dull texture to the background. The eraser was used as a drawing tool: where he erased to show the light glow surrounding the lighted candle. This is the brightest light in the work. Notice the way in which the eraser was used to emphasize the halo surrounding Christ's head. The foreground has the darkest values and the mid-ground appears lighter and the background is even lighter. The body of Christ is highlighted on the side which appears nearest to the viewer. The bended head's shadow is much darker.

The work has the women in an elongated rectangle form and the Christ figure is in a narrower rectangular form. His treatment is architectural in design as are all of his compositions. Ramos Martinez used lines in a dramatic way. He has bold lines, broken lines (the line that repeats itself) and pure lines (thin and precise lines) and lost and found lines (lines start out dark and fade away). The strong vertical lines of the female figures create a sense of strength and stability. Note the diagonal lines in the background, which create drama. He has used this in many of his oil paintings. Examples: "Mother" circa 1930 oil on canvas , "The Indian Woman" circa 1936 oil on canvas, "Peon en Blanc", "Camelias Blancas", and "La India de Tehuantepec".

Conclusion

Ramos Martinez emphasized naturalness and simplicity in his art. He used architectural and geometric forms. He understood how to express sorrow in the Two Women Before the Crucifixion. His religious background enabled him to express the religious significance and grief the two women experienced from witnessing the crucifixion of Christ.

Prepared for the SBMA Docent Council by Carolyn Pappas 2006.

Bibliography

Griscom, Elane, Behind the Hedges of Montecito, Fithian Press , Santa Barbara, California 2000

Louis Stern Galleries, Ramos Martinez, October 1991-January 1992

Museo de Arte Contemporaneo de Monterrey, agosto 1996-febrero 1997

Ramos Martinez, Maria Sodi de, Alfredo Ramos Martinez, Los Angeles, Martinez Foundation, 1949

Small, George Raphael, Ramos Martinez His Life & Art, F & J Publishing Corp. 1975

Internet

Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent papers

Ramos Martinez working on a mural at Scripps College