Fairfield Porter

American, 1907-1975

Morning Landscape, 1965

oil on canvas

79 1/2” x 80 in.

SBMA, Gift to SBMA from Mrs. Rowe Giesen

1991.87.1

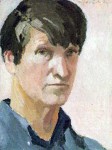

Fairfield Porter, Self-Portrait, 1972, Oil on Masonite, Parrish Art Museum, Southampton, New York

RESEARCH PAPER

Morning Landscape was painted on Great Spruce Head Island off the coast of Maine in 1965. Just before this annual summer trip, Porter had been in an automobile accident with no permanent damage, but considerable shock to his system. The whole summer was spent recuperating. Nevertheless he completed several major paintings, one of them being Morning Landscape. The painting is an enormous, brilliantly colored image of the harbor view from his house with his daughter Elizabeth sitting off center to the right. Porter described this painting to a visitor as a view he saw on awakening on a particular morning. The painting has a very low vantage point, cutting off the figure at knee level. Perhaps this shows the influence of the “cut off” technique used in Japanese prints. A number of them hung amidst the rest of the happy clutter of his households. More likely it is because he wanted to frame the picture with the outline of the framing of the screen porch in which she is sitting. Porter provides the best description himself in a letter he wrote to his brother Lawrence. "I have a very large painting…which has Lizzie sitting on the front porch in Maine with all the morning harbor view behind her, all in pink, cerulean, pale orange and gray. Lizzie is in scarlet. And on the left of her are pink and purple Canterbury bells and foxglove planted the preceding year by Jimmy. The island was very, very dry and the grass turned the color of rock.” (Spring 276) The Jimmy referred to was James Schuyler, Pulitzer Prize winning poet who lived with the Porters, on and off, for 12 years.

Justin Spring, in his biography of Porter makes special note of this painting with the following description:

The work is one of Porter’s most joyous, in part because the open, almost mischievous expression of Elizabeth harmonizes so perfectly with the fresh bright morning sun on the landscape behind her and the flowers to her right. In her funny scarlet hat and sweater, Elizabeth has the cheerful presence of a cardinal; here Porter’s color combination of scarlet and ocher is a departure for he had frequently paired ocher with a deep, vivid orange during the 1950’s. The porch architecture-its roofline and bug screens-frames the view beyond Elizabeth, which moves easily between representation and abstraction and is concerned primarily with color harmonies. The interior light of the porch gives way to the vivid daylight of the middle ground with “its grass turned the color of rock”; soft, opalescent outlines of the misty harbor and cove finish off the view. There is a wonderful, airy casualness to the work; the complicated forms of the spruce tree to the left and the wall of trees on the far side of the cove seem merely to have been drawn in outline and then blocked in. The dry surface texture of painting along with its use of bright colors, recalls the glories of fine weather, particularly the specific moment in midmorning when the soft haze begins to burn off and the dry summer landscape is revealed in all its splendor. Again, Porter’s use of a large canvas, a convention among Abstract Expressionist painters, counts as an innovation and experiment in this work which is essentially Intimist. (String pps. 277-278)

Porter’s most fruitful creative period as an artist lasted only a relatively short time. After much work, he finally found his own voice, his own way and this led to recognition in the last twenty years of his life. Morning Landscape was one of the best of the best of this period. SBMA is fortunate to have a great painting from an artist whose reputation should continue to be enhanced with time.

Biography:

Fairfield Porter was born into a patrician New England family, but grew up in the Midwest. His father, James Porter, a frustrated biologist turned architect managed the large chunk of prime Chicago real estate on the Loop which had made his family rich. Porter was raised in the family home on the lakeshore in Winnetka, a suburb north of Chicago. The home he shared with his brothers and sister was a Greek Revival mansion designed and built by his father. Porter was number four of five children but never wholeheartedly felt part of the group. An example of his family’s coldness towards him was when his youngest brother was born when Porter was three. Porter’s given name was John Fairfield Porter, but when the new brother arrived his parents decided to call him John instead. Porter was then called by his middle name, Fairfield. On top of that, he was taken to the barber and shorn of his long locks. His parent’s lack of sensitivity to their children’s feelings was simply part of their Victorian notions of child rearing. His father’s behavior towards him was distant and impersonal with no show of warmth whatever. Some maintain his father actually disliked him, perhaps all the more because he was an intellectual nuisance. Nevertheless, his father’s impromptu seminars, in the natural sciences and geology on their Sunday nature walk, left an indelible impression on Porter. From early on he took delight in attentive observation of the natural world. His mother, however, doted on her son and was zealous about educating him to the cultural riches of art and to liberal social causes. Her New England predecessors, who included Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, were involved in abolition and the women’s suffrage movement. A graduate of Bryn Mawr, Ruth Furness had returned to Chicago to teach elementary school, fired with the strong social conscience she had developed in college through her association with friends who worked at Jane Addams’ Hull House. Her marriage to James Porter compelled her to change her role in life from educated professional to wealthy suburban matron with five growing children and two households to maintain. The situation was problematic at best and her outpouring of intelligence, and industry towards grooming her most sensitive child to a life of culture and service, must have helped channel her abundant energies. Significantly, Porter’s first memory of looking at a painting is a visit to the Art Institute of Chicago with his mother.

In this grand household where money was never discussed or referred to, Porter struggled along. A slow reader initially, he devoured the classics. His art inclinations were encouraged by his mother and grammar school teachers. However, by the time he reached high school, two years ahead of his peers, he was seriously lacking in self esteem,” a quiet, awkward adolescent, paralyzed by self consciousness about his appearance, his lack of physical prowess and a vague but persistent sense that he was somehow not acceptable.”(Spring, p. 15) “Furl” as he was known at home and “Clammy” at high school, was sent to Prep school for another year after high school to do some catching up, physically and socially, before he entered Harvard.

In the meantime, his father an inveterate hobbyist and tinkerer became engrossed with the purchase of a 200-acre island off the coast of Maine in Penobscot Bay. There was no habitation on the island except a small graveyard. He bought the island, Great Spruce Head, for ten thousand dollars and proceeded to design a large summerhouse for his family. This property, which was to become fundamental to Porter’s work as a artist, and indeed, his world view, became the place to which the family traveled every summer. “The Big House”, as it was always called, was set on top of a slope at the island’s north end to take advantage of the spectacular views. John Marin, whose work Porter was to be introduced to through Stieglitz in New York much later, had his summer residence at Stonington nearby.

At Harvard, Porter was an indifferent student. However two people made a lasting impression on him. The first was Arthur Pope who taught “Drawing and Painting and Principles of Design”. Porter was knowledgeable in art history by the time he was fourteen due to growing up in a house filled with copies of Renaissance paintings and plaster casts of Greek sculptures and trips to Europe with his family to see the real stuff in situ. Pope’s course inspired him to become a painter. His other mentor, Alfred North Whitehead, had a lasting effect on Porter’s writing and thought, providing the philosophical underpinnings or rationale for what he was to do later with paint. By posing the question,”How does one know what one knows?” Whitehead offered the approach that such knowledge could come through both poetry and direct experience.

After his junior year, in the summer of 1927, his mother sent him and his brother Edward on a tour of Europe for the summer. After visiting and sketching the cathedrals and chateaux of France, a chance encounter enabled Porter to join a group of Americans traveling to Russia. Porter, who had a long-standing interest in Russian literature and also in leftist causes, was fascinated with the drama of recent events in Russia. Not only did he get to see Impressionist and Modernist art in the great collections which had just been opened to the public, but he and his group were permitted an audience with Trotsky. He dutifully made a sketch to memorialize the occasion. After the excitement of Russia, Porter seemed to find his senior year irrelevant. He barely graduated but listed “painting “ as his future profession.

That year, 1928, he moved to New York and enrolled in the Art Students’ League. His principal teacher was Thomas Hart Benton. Porter enthusiastically immersed himself in the vibrant art community of Greenwich Village. He became acquainted with Stieglitz and admired the work of the new modernists. He identified with the message of the Mexican muralist, Orozco. Despite the fact that he thought his son had no talent; his father sent a monthly stipend. Not having to work was a mixed blessing for among his painting peers he sometimes felt like an outsider. He persevered for two years at the League but became more and more turned off by Benton’s approach and couldn’t find much satisfaction with his other teacher, Boardman Robinson. He was frustrated. Nobody was teaching him how to paint.

He hoped to solve this dilemma by more travel to view the art of Renaissance Italy. His mother concurred and financed a year abroad. In the meantime, he had met his wife to be, Anne Channing, a poet, and entertained her at Great Spruce Head. Porter recorded his discoveries and impressions abroad in great detail in letters to both his mother and Anne, a habit he maintained throughout his life. A highlight of this year was his association with the renowned art historian, Bernard Berenson. Porter was a frequent guest at I Tatti, his home in Florence. His painting time was spent copying the Old Masters. He also visited art museums in Berlin, Munich, Dresden, Barcelona, Madrid returning home via Paris and London. It was his last visit to Europe until 1967.

He married Anne Channing from Boston soon after his return. Deciding to settle in New York, Porter studied anatomy at Cornell, dissecting cadavers. He was a member and teacher at Rebel Arts, a socialist art group. He wrote his first art critique, which was published in The New Masses and dealt with the socially conscious murals to be found in N Y at that time. In 1934 his first son, John, was born. The event was to affect his career profoundly as it became apparent that the child was not developing normally. Porter, who was a reluctant father, no doubt because of the lack of love he felt from his own father and because it distracted him from his purpose of becoming an artist, nevertheless pitched in with great devotion in trying to deal with this atypical, difficult child. He and his wife exhausted all the medical assistance available and got no answers except that the problem was “their own fault”. Today the child would be recognized immediately as autistic. To complicate matters another son, Lawrence, was born two years later. For the next 8 years the Porter family lived a peripatetic life, even moving back to the Chicago area to live in Porter’s grandmother’s house. During these difficult times when Porter’s income was also diminishing, two very important events took place, which were to have a major effect on his mature work as an artist. He met and became friends with Elaine and Willem De Kooning. He bought several paintings, among them the famous Pink Lady, which he later had to sell when pinched for money. He attended an exhibition of the works of Bonnard and Vuillard at the Chicago Art Institute. In Vuillard he found a true soul mate. “What I like about Vuillard is that what he is doing seems to be ordinary, but the extraordinary is everywhere. (Moffet, p. 32) Vuillard, by validating Porter’s choice of subject matter, freed him to be himself and paint what was closest to him.

During the war years,1940-1945, another son, Jeremy, was born. Porter hired on to do “war work” with a drafting company, principally drawing illustrations for the navy of gun mounts. He also began taking night classes at Parsons School of Design with Jacques Maroger, a former art restorer at the Louvre who taught Porter to use a new medium he had developed which Porter came to prefer above all others. Except for a short time when he experimented with acrylics, he prepared his own paint in this exacting way. The medium was a smelly amalgam of boiled beeswax, lead carbonate, and raw linseed oil, which when mixed on a palette, made oil paints fluid, yet thick, and very slow to dry. The new technique proved to be a real turning point according to John Spike in Porter’s recent catalogue raisonne by permitting the self critical Porter to paint rapidly and freely, while retaining the option to change his mind a day or so later. The beeswax in the medium gave his paintings a richly textured surface that they had previously lacked. (Spike in Ludman, p. 35)

The day the war ended Porter quit his job and refocused his energies on painting. He went back to studying the Old Masters and was accosted while sketching in front of a Tiepolo by Georges van Houten, a Belgian painter who had been active in Paris and had known Renoir, Degas, Vuillard and Bonnard. He agreed to give Porter some lessons. His advice was “to keep seeing light in everything, to see light even shadows, and above all to see light rather than pigment in paint”(Spike, p. 35) According to Spike, these two factors, a new medium and a new teacher who provided verification and encouragement marked Porter’s birth as a mature painter. In the quality of his light and the new luminosity of his colors, he was able from 1945 on to make his paintings as individual as the moments in his life.

In 1949 the Porter family moved from their home on East 52nd St to a grand and dilapidated old house in Southampton on Long Island. The change was critical to Porter’s work for it was here and at Great Spruce Head in Maine that he was to paint the majority of his paintings. His household grew with the addition of a daughter, Elizabeth. The barn at the back of the property became Porter’s studio. On weekends the house was filled with an assortment of guests from poets to fellow painters. Another event began to inform his paintings. During a visit to the Metropolitan, he saw some Velasquez paintings he had seen long before in Berlin. This time he was struck by what he called the liquid surface of Velasquez and his understatement. In his own words: “He leaves things alone. It isn’t that he copies nature; he doesn’t impose himself. He is open to it rather than wanting to twist it. Let the paint dictate to you.”(Spring p.157)

In the fifties Porter’s life improved immeasurably. His rocky marriage settled into a predictable pattern. His autistic son was placed with foster parents in Vermont and Porter was able to devote most of his energies to his painting. He also began to write for Art News and later The Nation. It was a process he greatly enjoyed because it allowed him to measure his own work against those of others. His work was finally being recognized, despite the monopoly of the N Y School of Abstract Expressionists. From 1951 until 1970 he had fifteen exhibitions in New York.

In the sixties he continued to have a number of one- man exhibitions. He continued to write and enjoyed teaching. In 1969 he was artist- in- residence at Amherst College. His brother Eliot, inspired by his contact with Steiglitz through Porter in years past, had become a well-known nature photographer. Both exhibited together and received an honorary degree from Colby College in that year.

Until his untimely death from a stroke at age 68, Porter continued to produce paintings of his personal reality: portraits of friends and family, interior and exterior scenes of his living spaces in Southampton and in Maine where he spent each summer. His works document an American worldview, an American life, such as his predecessors Homer and Eakins but with contemporary means. Even though Porter never eschewed representation, his concepts and execution had strong elements of the abstract, in the loose broad-brush work, in the articulation of space, in the large size of his canvases. The jury is still out on this painter. I think he is yet to find his proper place of prominence among artists of the twentieth century. John Russell, art reviewer for the New York Times had this to say in 1983: These paintings present us with an America in which pollution, family strife and even the notion of bad weather have no place. The more we know about the painting, the more we recognize the exceptional daring of Porter’s use of color and the freedom and energy with which he went to work with the brush…as if they had been painted the way a bird sings—natural, without effort and without interruption.

Bibliography:

Ashbury, John and Moffet, Kenworth

Fairfield Porter (1907-1975) Realist Painter in an Age of Abstraction,

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Mass. 1982

Downes, Rackstraw, ed.

Art in its Own Terms: Selected Criticism, 1935-1975 by Fairfield Porter

Zoland Books, Cambridge Mass., 1993

Ludman, Joan, Fairfield Porter, A Catalog Raisonne of Paintings, Watercolors and Pastels

Hudson Hills Press, New York, 2001

Spring, Justin

Fairfield Porter, A Life in Art

Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2000

Prepared for SBMA Docent Council, April, 2004 by Gay Collins