Lari Pittman

American, 1952

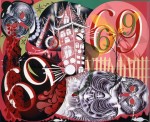

Transcendental and Needy, 1990

acrylic and enamel on mahogany panel

66 x 82 x 2 in.

SBMA, Museum Purchase, Ludington Deaccessioning Fund

2009.61

Lari Pittman. © 1990 Ann Summa.

"Radiant and Needy," 1992 (above right), acrylic and enamel on mahogany panels, 48 x 36 in., Private collection, Los Angeles. Photo by Douglas M. Parker Studio. Courtesy the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

"The remembrance of death- memento mori- is a big part of the work. And, again, it’s bittersweet because you want to commemorate death but you are consumed with the mandate of aesthetics. So you have to fuse within the object the mandate to address life and death, and then the formal mandate to address aesthetics and connoisseurship. They must be fused together in the object." - Lari Pittman

COMMENTS

Lari Pittman’s paintings indulge a sensualist’s love for the visceral. Rendered with a fanatic’s precision, his Victorian silhouettes: imaginary organic forms, runawayarrows, and arabesques, transform ornamentation into a contemporary narrative of life and death, love and sex. Frenzied yet sophisticated, Pittman’s operatic pictures propose that the world’s complexity does not override passion, sincerity, and individuality.

A Los Angeles native of Colombian heritage, Pittman was born in 1952, attended UCLA, and graduated from CalArts. Inspired by the school’s strong feminist program—which challenged the devaluation of art forms traditionally associated with women—Pittman embraced decoration. His paintings combine meaningless “surface embellishment” with “outdated” figurative imagery. Since 1983, Pittman has had annual solo shows at Rosamund Felson Gallery. He lives in Echo Park with Roy Dowell, who’s collaged abstractions influence and play off Pittman’s promiscuous pictures. History?—Who is he? Where’s he from? Where’s he live, paint, show? Who are his contemporaries? Etc. etc.

David Pagel From each body of work to the next, your paintings change quite a bit. Do you have a plan?

Lari Pittman For the last ten years, at the beginning of each body of work, I make a list of things I can no longer do. When, in previous bodies of work, there would be text, no more text. Or, in the last body of work with the psychological and sexual narrative, no more for the next. Aspects of the sense or sensibility of the work cannot be repeated, even though I might be drawn towards doing so. It’s a sweet deprivation. Whether it’s a romantic notion or not, at least to me, it must seem new. I don’t really know what new always means, and I think that that is a romantic concept.

DP That it’s fresh or it’s something unexpected or discovered?

LP Mm-hm, for me. And hopefully that will translate to a broader world, or at least the world that I am painting. I mean I have no tolerance for boredom.

DP (laughter)

LP I’m very allergic to my own mannerisms. In other words, I think that the work has always been mannered but if the mannerism is repeated, I rebel against it and that’s why the work changes.

DP The last body of work was titled . . . was there a title?

LP All of the paintings have the same title, Beloved and Despised, Continues Regardless. And then it becomes: This Desire, Beloved and Despised, Continues Regardless; This Wholesomeness, Beloved and Despised, Continues Regardless; This Machine, Beloved and Despised, Continues Regardless. It’s a litany of sentiment. There are aspects of behavior that are entrenched and change very little. And aspects of desire or longing that are very strongly entrenched. And there’s discussion on both sides—they’re either loved or despised. And there’s really not much you can do about it.

DP There’s a lot of sex and death in these paintings.

LP Yes. (laughter) Sex. Death. But then life and love are further declensions of those. Life, being a segue from sex to death, and love and sex, and all those intertwinings. But it’s not about polarizing them which, at this point, American culture is incredibly adept at. It’s really about democratizing their function within a larger setting: that sex is equal to death, that death is equal to life, that life is equal to love. One doesn’t supersede or exclude the other. In reality, it’s much more inclusive. And if indeed, they can disembody one from the other, it’s our puritan heritage that has polarized these concepts. Because actually, life, sex, death, and love sit very comfortably next to each other. They’re not in opposition. The object of that body of work was to clarify aspects of this. My own particularized sexuality is not necessarily the lens through which I view sexual activity or desire. The work has always embraced a much broader form of sexuality and sexual activity. And that pan-sexuality was literally shown in the work. It’s funny and somewhat ironic because I’m beginning to feel that it’s incredibly outdated in attitude (laughter).

DP Or just up in the future a little bit.

LP Hope?

DP Yes. (laughter)

LP That’s very kind.

DP Lately, sex and death have been brought together pretty closely with the AIDS crisis. Were you thinking of that in the work?

LP I think that course is inescapable. But this is in a culture that has steadfastly kept them apart. Out of this trauma and tragedy of the AIDS crisis, what I would like to see are the healthy ramifications—that because of this our culture can incorporate concepts of mortality. It can become a very natural filter, which it should be, through which you view and appreciate life. There is no such thing as “Now we’re alive and now we’re dead.”

DP Were you born in Colombia?

LP No. But my mother’s family and my mother are Colombian, my father’s family is American. And I think that was a vantage point to see how American culture functions.

DP So you had one foot in it and one foot outside.

LP The added thing, the one foot in and one foot out, is being homosexual. I’ve always, as an artist, seen those as really advantageous positions from which to view culture. I like being slightly outside, but maybe I also don’t have much choice. (laughter) But I insist that it be an advantage.

DP Your work is incredibly optimistic.

LP Again, I don’t think we have much choice, do we?

DP I don’t think so. But there isn’t much optimistic art being made these days.

LP One can be incredibly critical of culture and still be equally optimistic or perversely optimistic about it. One can be dissatisfied: with one’s life, one’s relationships, one’s culture, one’s specific, immediate world; but sitting next to that is an insistent optimism that it can be better. The core of cynicism in American art of the last decade is linked to a xenophobic cultural era which artists are not above and beyond, artists still believing in first world culture. They aren’t privy to observations of the world culture. Since “first world cultures” are having a hard time, you assume that there’s no hope for the world, no hope for culture, or your own immediate world. American artists are not beyond those gross assumptions—the intrinsically offensive concepts of first and third world culture. That is what I mean by cultural or xenophobic arrogance. A word I’ve never been scared of even though it has, in recent times, been insistently linked to modernism, is the word “visionary.” I don’t pejoratize that word, and I don’t necessarily link it to modernism. That is a link, but that is only in terms of art. (laughter)

DP Well, that visionary look was otherworldly, or it slipped off into the clouds pretty quickly. Whereas, yours is picking up the pieces and stirring them up.

LP The work has always been hopeful but part of it is that I can’t remove my work from my life. That insistence on projecting into the future with some criticism, but hopefulness, kicked into even higher gear five years ago when I was shot.

DP I read that; in your apartment.

LP And critically wounded. I had a hard time recovering. If you are so violated by violence that personally, not only do you have to physically reconstruct yourself but you have to start from scratch philosophically. And I found that completely liberating.

DP That was in ’85, yes? (Yeah). And your work really did kick into high gear after that, it got more complicated, more dense and crazy.

LP Understanding mortality at a fairly young age opens things up instead of closing them down. What do I have to risk, rather, what do I have to lose?

DP So you risk everything.

LP I feel that. And I don’t mind the work being embarrassing or laughable. It doesn’t bother me. There’s a certain perversity to the work being ridiculed.

DP Oh, does it get ridiculed?

LP Perhaps in my romantic mind.

DP It’s some of the only work that really makes me smile.

LP But isn’t that, at this point, ridicule? (laughter)

DP No, I didn’t think so at all. It’s rare to go to a show and respond by scratching your chin, frowning and saying, “Mm.” You get that twist, that spin that puts a smile on your face. It’s not a silliness at all.

LP No, it’s a hysteria. At times, I purposefully orchestrate the work so that you do have that comfortable laughter when looking at it—it’s fullhearted and enjoyable internally—but it’s also a laughter linked to nervousness. And that’s the laughter I particularly like cultivating, parlor laughter, where there’s always the subtext of conversation going on, but everyone is very agreeable.

DP Uh-huh, keeping it on the surface. You don’t think of your work as particularly Los Angeles or California?

LP No. That’s not an issue. It’s made here, though. (laughter)

DP But at one point you chose not to live in New York?

LP Well, being an artist is certainly an important factor in my life, but of equal importance are my personal relationships. And those actually take precedence many times. Career is wonderful and satisfying, but . . .

DP It’s not the bottom line.

LP It’s not the bottom line, and I don’t like an empty bed. To put it bluntly.

DP What led you to the Victorian silhouettes—end-of-the-century sensibilities, contemporary prudishness?

LP I’ve always employed elements of abstraction and narrative, and I never know really how to resolve them, I don’t think I ever will. In this last body of work, I wanted to increase the narrative. The way to do that is to put ourselves into the work—the figure. But I didn’t necessarily want to paint the figure, hence the idea of the silhouette. But I didn’t want to do contemporary silhouettes because then we could say, “Oh, there I am in that painting. I’m that type. I look like him or her.” That’s already an identification that gets too immediate, too fast and too close. Since they are from other centuries, you’re not identifying with types of people but types of behavior. Even as a male, you could stand in front of a female and say, “I behave like that.” Or conversely, they contain the possibility of crossing gender and sexuality by identifying with behavior and things. And behavior has changed, unfortunately and fortunately, very little. So it was a way of making the work more narrative. Sometimes I rebel against levels of abstraction. Unlike Roy Dowell—the water he feels completely comfortable swimming in is abstraction. You know, we’ve lived together for almost 16 years.

DP I didn’t know that.

LP And that’s been our difference as artists.

DP But you both flirt with the other sides.

LP Of course! How could we not? And we influence each other tremendously. Vocally, there’s a symbiosis. But I’m more drawn or driven to picture-making that has a sentence to it. Periodically, we do distinguish our work. And we’re aware of where it meets and crosses. We have made very distinct decisions to move away from each other or to separate the work. And many times that reinvestigation is the reinvestigation of the stronger points. In my case, I’m happiest with the work that tends to be more conversational and chatty. I literally ask myself, “Lari, what do you want to see in your work?” I would look at this thing, which is very dead—a painting’s a dead, pathetic thing if we’re gonna talk about it. It is. It’s a sad thing.

DP Do you always paint on mahogany?

LP Wood.

DP Any kind of wood?

LP Mahogany. And so I wanted to look at this thing that’s dead, and have you walk in on this intense chatter and conversation and engagement and activity. That’s what I wanted to see in the work. The increase of the narrative actually then becomes a way of giving life to the painting. And in that sense, it has a full life of its own. It’s mildly indifferent to the viewer, which I like.

DP More than mildly. (laughter) It seems as if it can carry a conversation on its own, even if no one is in the room.

LP I hope so. I hope so. The pedigree of the viewer, the knowledge of the viewer, the willfulness of the viewer, is not the main operating battery that empowers the painting. Hopefully, the viewer comes upon the work and it’s alive and functioning on its own—at full throttle.

DP Do you think that just painting is dead or do you think any . . . ?

LP Not dead, but lifeless to people. What we’re seeing right now is a reliance, very heavily, on materiality. There is something that materiality brings to it that’s different from illusion—a different type of life. I’m wondering, if the reliance on materiality is, at its core, an incredible conservativism? I’m feeling that.

DP You dream in illusions. You don’t dream in materials.

LP Well, but also, I love the property of things. I’ve tried to do three-dimensional work . . .

DP What have you tried?

LP Well, I’ll look at this last body of work with the silhouettes and think, “Why don’t I literally create these tableaux?” But then I’m always slightly dissatisfied with the materialization of these pictures. It always leads to disappointment. One of the things I rely on in picture making is that it is illusion, and therein lies a certain ephemerality. And all of a sudden, when you’re making something concrete . . . it makes me nervous.

DP It’s more of this world.

LP Yes. I don’t think you can project or dream as much.

DP Do you think abstract paintings are more in this world? Ones that deal with materials? They’re somewhere between an illusionistic, representational image and sculpture or three-dimensional things?

LP I have tremendous respect for abstraction, and I envy it, actually.

DP Oh, really?

LP But I wouldn’t know how to go about doing it. I don’t know really how to do it. But in my hierarchy, it’s very high on top.

DP But your older works are more abstract. Or I guess the narratives are more vague.

LP The narratives are more vague, but if indeed it was abstraction, it was very strongly linked to what has been termed as biomorphic or biological references.

DP You still have the plant forms in the work. You always get this sense of organic life teeming up and decomposing and rotting and starting over again; seeds growing. That’s carried over.

LP The idea of cycle has always been a part of the work and always will be. The fascination with cycle is my utter fear of it.

DP How so?

LP I get tremendous anxiety during the fall. I don’t plant anything that loses its leaves. I have a very hard time with that.

DP No kidding? So that’s why you’re not in New York.

LP Evergreen. Everything has to be evergreen.

DP Always full of life, yeah.

LP (laughter) I have a hard time planting perennials. I’m sorry . . . what is that? I’m fascinated with the pulse of birth and decay, birth and decay. But at the same time it’s horrifying. You know, repulsion is fascination.

DP In one painting, you have the cycle of the commodities circling around. Instead of plant life or organic life being born and rising, growing old and dying, you have cars and video cassettes and TVs. The urban or cultural equivalent of that process.

LP Regardless of ideas of romantic love, there is an insistent and very strong aspect of bonding that is about economics. That is also a very strong beat to relationships. And whether it’s there at the beginning or not, it’s certainly formed at some point. Relationships are not simply informed by concepts of romantic love. There is a very distinct and tawdry expediency to why people bond.

DP The nitty-gritty, economic underside of it. Do you have a favorite piece?

LP I like qualities in pieces that I’ve made. I like when I overstretch myself. When it’s beyond my grasp and it alerts the viewer that I’m trying too hard, not in terms of dimension or size or materials, but in trying to tackle something enormous, this tremendous, elegant endeavor. There’s a pathetic quality to that type of overreaching, in trying to say something. It’s embarrassing that I even had that ambition and that I wanted to say so much. And that becomes touching but pathetic at the same time. And that is a quality that is romantically linked. But I like that in the work. People will respond, “Oh, come on, Lari, please stop!” (laughter) If I have favorite pieces it’s because I secretly know how they relate to my life more directly. But that’s personal and really of no use to the public. (laughter) This Wholesomeness, Beloved and Despised, Continues Regardless, where, at the bottom half of the painting, two men meet and construct a bridge that emanates from their erect penises. And in the evening, they’re done with the day’s labor. The bridge is in the background, fully employed by pedestrians crossing over, and they’re lying on the bank of the river where the bridge spans. It is about desire becoming real, desire becoming productive, and desire producing something of use to a broader world—this physical bridge. And then, simply, a celebration of that accomplishment. But, in this case, it was all being accomplished by people of the same gender. So I think that is a favorite of mine. I’ll say it. (laughter) It’s a favorite of mine. Ironically or maybe very purposefully, even though the painting is centered around this dynamic, two men, it has nothing to do with sexuality.

DP Nothing directly?

LP Not really. This is a much greater bond than physicality or sexuality might intimate. In reality, the core of this emotional and sexual bond is not about a certain desire or attraction to each other. In the painting, it proposes that the outcome is something else which is building.

- David Pagel, Lari Pittman (Artists in Conversation), BOMB 34, Winter 1991

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Lari Pittman is inspired by commercial advertising, folk art, and decorative traditions, meticulously layering his lexicon of imagery into opulent scenes that are as visually compelling as they are psychologically complex. Transcendental and Needy is from a series of paintings prominently featuring hermaphroditic owls and other symbols that appear in his work from this period, including silhouettes of towers with faces, the number 69, arrows with the message “this way out,” a microscope, and tear drops. This particular work is most certainly about death; it references traditional parinirvana, or death of the historical Buddha, while also alluding to the casualties brought on by the AIDS epidemic, which by 1990 had become a major concern of the art world and American society at large.

- Ridley-Tree Gallery, 2016