Max Pechstein

German, 1881-1955

The Old Bridge (Die Alte Brücke), 1921

oil on canvas

16 1/2 x 15 1/2 in.

SBMA, Gift of the Joseph B. and Ann S. Koepfli Trust

2011.2

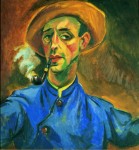

Max Pechstein, Self-Portrait, 1918. second image above right, Der Muhlengraben, oil on canvas, private collection in Germany. This painting of the same year also depicts the canal with the wooden bridge in the distance. The color palette, too, resembles that of Pechstein's work in the SBMA collection.

“Work! Ecstasy! Smash your brains! Chew, stuff yourself, gulp it down, mix it around! The bliss of giving birth! The crack of the brush, best of all as it stabs the canvas.” - Max Pechstein

RESEARCH PAPER

Upon viewing the painting Die Alte Brucke (The Old Bridge), one is struck by the artist's use of pure and primary pigments, red, blue and yellow leap from the canvas. In fact, the painting itself appears like a neon sign, difficult to turn away from yet overwhelming to the senses. Adding further to the contrast, Max Pechstein has outlined in black all the figurative elements reminding us of stained or leaded glass. The painting is divided into three clear sections with a definite background, middle ground and foreground. Brush strokes are flat and wide suggesting a harsh, primitive scene.

In the background, outlined in black and painted in ardent red, is a large industrial building. Six large flat smokestacks or chimneys rise above the multilevel roof. The building does not recede into the background but rather stands as an imposing structure and form on the canvas. Small windows disclose a faint amount of light emanating from within the building.

The ocher bridge in the middle ground, divides the canvas in half. Painted on the diagonal, the bridge divides the canvas both laterally and diagonally. The bridge railings, walkway and pilings are outlined in black as well. Crossing the bridge are three men dressed in blue uniforms, outlined in black. Their faces are crude; their forms are angular, without detail and without expression. They appear only as a mention, as we can't see their expressions though their movement and determination are unmistakable. The bridge and the figures walking across it contribute the rhythmic motion of the piece.

The foreground of the painting is a blue and green reflecting pond. The bridge pilings are reflected onto the murky green water's surface at exaggerated wide, flat angles. The entire picture is cooled and balanced by the color blue. In the upper left hand corner is hint of a beautiful clear blue sky. And in the lower right hand corner is the clear, blue pond.

There is the sense that we are peering in on a scene as the canvas is framed with the leaves and foliage of the hillside we are standing on. The foliage helps to soften the harsh, angular and flat scene of men going about their day of work. But, the painting remains devoid of feeling and sentimentality. It is only in analyzing Pechstein's artistic career that we might come to an understanding of his intention.

Considered by art historians as the most representative of the Die Brucke group of German Expressionism, Max Pechstein joined the group after completing his studies as a decorative artist in 1906. He was the only trained painter in the group as the other members were trained architects. His commissions in the decorative arts, in particular his commissions to do stained glass, are visible in this painting as the objects are flattened and held in place by harsh black outlines.

The Die Brucke group founded in 1905 by Erich Heckel and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner has been credited as "a fountainhead of (artistic) experimentation and creative activity that did much to give German Expressionism historical significance in World Art". (Cassou, Langui, Pevsner) Responding to the bourgeois notions of art, specifically the plastic art of Expressionism, the group named themselves Die Brucke (the bridge), as a declaration of their intention of bridging the old to the new. They embraced the spirit of Nietzsche, proclaiming themselves as non-conformists, anarchists, revolutionaries but always humanitarians. Pechstein though the more conservative of the group was in fact the most popular and financially successful in the group.

Upon final look at Die Alte Brucke (The Old Bridge), we see three men crossing the bridge. There are two men following in the same direction, toward the building. The third man at the apex of the bridge is coming towards us in the opposite direction from his fellow workers. In 1910 (the time this piece was painted) Pechstein was abolished from Die Brucke for exhibiting his work with the Berlin Secession without Die Brucke's consent. One has to wonder if this is not Pechstein's visual double entendre?

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Teda Pilcher April 5, 2012

POSTSCRIPT

The Santa Barbara Museum of Art was fortunate to recently (2011) be given a painting that has been on loan to us since 2005: Max Pechstein’s The Old Bridge, c. 1910-1911. If you’ve visited the Museum in the last few years, you’re probably already familiar with this vivid image of a German village with its strong colors and boldly simplified forms – but you might not be aware of the importance of this painting to Pechstein’s career and to the history of modern art.

The significance, it turns out, is all in the name. Pechstein was part of a group of young artists based in Dresden who called themselves Die Brücke – “The Bridge.” Inspired by the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, the artists of Die Brücke sought to throw off the materialistic values of the past and create a bridge into the future. The “old” bridge in this painting not only alludes to the group’s name, it also represents both the conventions of the past and Pechstein’s determination to move past them in the creation of a new, emotionally authentic art that spoke to the concerns of his own time.The Old Bridge originated during Max Pechstein’s first summer stay in the Baltic coast village of Leba (in present-day Poland). It is figurative, but the artist is not exclusively interested in the subject matter; he also emphasizes the color and light contrasts of the scene, juxtaposing the red of the houses and the green of the trees, as well as the yellow of the bridge’s wooden beams and the blue and green of the water. The different areas of color are surrounded by darker contours, adding to the impression of flatness and to the intensity of the color scheme, a painterly technique Pechstein had already adopted during his earlier membership in Die Brücke group more than a decade beforehand, which had probably been inspired by the work of his artistic hero, Paul Gauguin.

http://blog.sbma.net/2011/03/old-and-new-bridges/

Max Pechstein in his house in Berlin-Zehlendorf, 1915

COMMENTS

In his painting the artist depicted the town’s small wooden bridge, called the Kleine Mühlengrabenbrücke. The artist’s perspective can be reconstructed: he is right on the canal looking across the water onto the row of brick stone houses on the other side. It is a scene that he depicted several times over the years to come, in his oil paintings as well as watercolors and drawings. The three men in blue work overalls create a sense of scale, but they also point to a leitmotif in his landscape paintings, since they can be read as personifications of the timeless working life, consisting of fisher- men and agricultural workers, that he encountered far away from the metropolis of Berlin.

For decades, Pechstein had spent the summers away from the city of Berlin, preferably at the sea. These brief excursions over the summer months in order to escape city life and to collect new visual impressions for his artistic production were central to his artistic understanding. Unlike his Brücke colleague Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, who was equally interested in the depiction of city life, as manifested in his legendary Streetwalkers series, Pechstein preferred to focus on the rendering of landscape and village scenes, seemingly untouched by the industrial modern life that he experienced in Berlin. In spring 1921 he discovered a thin stretch of land in East Pomerania, between the Baltic Sea and a large lake, the Lebasee. In the summer of 1921 he, his wife Lotte, and their 7-year-old son Frank traveled from Berlin to the seaside village for their summer holiday. Pechstein stayed on in order to continue to paint and draw. He fell in love with Martha, the hotel owner’s 16-year-old daughter.

The painting ended up with the Berlin- based gallery van Diemen in the mid-1920s. Its co-owner Karl Lilienfeld, one of the most passionate collectors of Pechstein’s works for more than a decade, took the work with him to New York when he left Germany to open a New York branch of the gallery.

- Aya Soika, Professor, Department of Art History Bard College Berlin, 75 in 25 Important Acquisitions at SBMA 1990-2015, Catalog

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

The subject of this work may have been inspired by the scenery Pechstein painted with Heckel and Kirchner outdoors around the Moritzburg lakes near Dresden, but it is also likely a deliberate allusion to the group’s name Die Brücke, derived from Friedrich Nietzsche’s "Thus Spake Zarathustra" (first published in 1891). For these artists, Nietzsche’s philosophy represented a rejection of materialism and bourgeois values – a bridge to the future. The thin application of paint approximates the look of fresco or tempera. The allusion in the title to an “old” bridge may reflect the group’s evolution away from the thick impasto of van Gogh and toward this kind of paint application, in which the individual hand of the artist is less conspicuous.

- 20th Century European Art, 2021