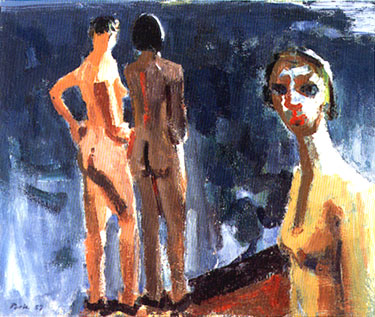

David Park

American, 1922-1960

Three Women, 1957

oil on canvas

48 x 58 in.

SBMA, Gift of Mrs. K. W. Tramaine in honor of Mr. Pau Mills' appointment as Director of the Santa Barbara Museum of Art

1970.20

David Park at work in his studio in the 1950's.

“Park never at any time claimed that his figurative work was or should be the beginning of a separate movement. To him it was always basically in the abstract expressionist stream; the figurative aspect was just a personal device that made it easier for him to paint. As he said of his work in 1953 ’all of them are representations of definite subjects and otherwise probably not so very different from my former work.’ Further, in the later figurative things he achieved many of the very objectives of abstract expressionism which had eluded him in his non-objective paintings. His career as an artist is not the story of a switch from abstract to figurative; it is a complicated, fluctuating interplay of the two elements, both of which are always simultaneously present.” - Paul Mills

RESEARCH PAPER

Today it is almost impossible to over estimate the impact that Abstract Expressionism had on the life and minds of artists working in the United States in the late 1940’s and 50’s. Since 1933 when Hans Hofmann opened his school of painting in New York and his works began to be exhibited widely, his influence was profound. On the West Coast in the first decade of the ferment the movement was explosive, especially in San Francisco among the friends and associates of David Park.

Although his early years had been influenced by a variety of artists, from a teenage admiration for Maxfield Parrish, through Matisse, Bonnard, Picasso’s Cubism, Miro’s work of the 30’s, and Piero della Francesca, he seized on Abstract Expressionism as a release and revelation, much as his artist friends were doing. He threw himself into the movement with energy and daring, adopting the massive brush strokes, the thick and oleaginous paint, the large canvasses, accidental effects, along with the dependence on only an inner vision, the heart of action painting. But by 1949 he was taking a new look at the direction of his work, and dissatisfied with all but one of his Abstract Expressionist paintings, he took them to the Berkeley City dump.

Some understanding of his growth as an artist may be gleaned from a short resume of his life: He was brought up in the home of his father, a Unitarian Minister in Boston. His circle of family friends was well educated, which developed “highly articulate literary and philosophic enthusiasms” (Mills p5 Berkeley Retro). As we see in his life the Unitarian mind was not one which accepted the conventional wisdoms uncontested. He fell short of the family scholastic standards and did not enter college, but went to Los Angeles and enrolled in the Otis Art Institute. He remained there for less than a year, then moved to San Francisco where he lived for the rest of his life, with the exception of the years 1936-41, when he taught at the Windsor School, Boston. Form 1943 -52 (age 33-43) he taught at the San Francisco Art Institute (Then California School of Fine Arts), where he was in the middle of the turbulence that Abstract Expressionism was causing.

Some three years of energetic involvement with the theories and forms of this new movement led to deep introspection and the decision that following the trend was not true to his real interests as an artist, that his greatest enthusiasm was directed toward the figure. He needed the stimulus of finding subject matter in the real work, not an inner one. Starting with this new conviction, in 1950 he painted “Kids on Bikes” and submitted it to the San Francisco Art Association Annual in 1951, where is was awarded a prize, the only one for a figurative painting. It caused a flurry of critical comments; his friends didn’t appreciate that he had “chickened out” on the movement. Disillusioned with his fellow faculty members and disenchanted with Abstract Expressionism, he resigned. His wife, Lydia, was working at the library at U.C. Berkeley, and through the “Lydia Park Fellowship”, as he referred to her support, he was able to paint full time for the next three years.SBMA’s painting, Three Women, 1957 verifies this point of view. It is sumptuous in color, glittering with the oily thickness of the pigment as it is forced off the loaded brush, sliding over islands of the under painting color, but serene in content. The pose of the figures relates more the classical, cool figures of Piero della Francesca than to the impassioned and excited dabs of the action painters of the 50’s. And yet the actual application of the paint is in the mode of the 50’s, with a debt to German Expressionism and to the Fauves, in the emotional contrasts of the colors. The foreground figure, especially the face, with its blue-white tonality with the shocking contrast of green edges and dashing, violent reds evokes the portrait of Madame Matisse, Woman with the Hat, shown in 1905 in the first Fauves exhibition.

It was during the three years of full time painting that Park’s mature period evolved and that he began to achieve recognition on a wider scale. In 1955 he became a member of the faculty at UC Berkeley. There he was joined by Elmer Bischoff and Richard Diebenkorn, who worked together in figure-drawing sessions which led to an association of their work in exhibitions, and came soon to be called the “California School”. Park began to exhibit nationally both in one-man and important group show, and his work now entered major museum collections.

This mature period ended tragically with Park’s death from cancer at the age of 49 in 1960. It was really only in the last five years of his life that his ideas began to come together. It is interesting to read the critical reviews of his work published in the art journals of 1959 to 1963, particularly of the retrospective that toured the country, opening at the Staempflie Gallery, New York, in 1962. Sidney Tillim, Arts Magazine March, 1962 gave somewhat grudging praise of what he called Park’s “amplification of indefatigable and ingratiating diligence”; Vivian Raynor, Arts, Feb 1963, seemed uneasily trying to determine whether or not he was great; Martica Swain, Arts, Dec 1960, “his reputation now will surely soar.” Milton Kramer, Arts, Jan. 1960, declares that Park’s paintings “forfeit the figure to the fast brush"; while Jack Kroll, Art News. Jan, 1962, gave a somewhat indecisive resume of his style, then stated: “he stands in relation to Abstract Expressionism much as de la Fresnaye stood in relation to Cubism.” , which really wasn’t the point as it was out of Abstract Expressionism that he evolved his own personal statement, rich both in form and color.

Paul Mills remains his most able delineator in the catalog foreword of the Berkeley Retrospective memorial exhibition of 1964, and in the Maxwell Galleries 1970 catalog, where he says: “The bite of realism gave way to increasing interest in the nude, in figures symbolic of humanity itself rather than of certain persons in particular. His stylized patterns became increasingly richer in paint, freer in outline and more fluent in color. His flat forms gave way to corporeal volumes immersed in light and shadow.”

Bibliography:

Maxwell Galleries Ltd. 1973 Catalog of the Staprans-Park exhibition

San Francisco 1970 Catalog of the exhibition. Foreword by

Paul Mills

Univ. of Calif., Berkeley 1964 Catalog of the memorial exhibition

Herschel B. Chipp, B. H. Bronson,

Glen Vessels, Paul Mills

Santa Barbara Museum of Art 1968 Catalog of the exhibition, David Park, His World, 1911-1960. Goldwaithe H. Dorr III and David Park

Arts Magazine Jan, 1960 p 42 Milton Kramer

Dec, 1960 p 50 Martica Swain

Mar, 1962 p 36-37 Sidney Tillin, “Month in Review”

Feb, 1963 p 49 Vivian Raynor

Jan, 1965 p 78 Exhibition at U.C. Berkeley

Feb, 1965 p 78 comments on exhibition at UCLA

which included Park

Art News Jan, 1962 p 11 review of exhibition at Staempflie, New York

Feb, 1963 p13 review of exhibition at Staempflie,

New York (The retrospective exhibition that toured US)

Art Journal Fall, 1960 p 30 Obituary

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Docent Council

by Mary Cady Johnson, April 6, 1976