Carlos Orozco Romero

Mexican, 1898-1984

Formas tarascas (Tarascan Forms), 1939

ink, crayon, pencil, watercolor on paper

9 ¼ x 8 in.

SBMA, Gift of Mrs. MacKinley Helm

1969.35.33

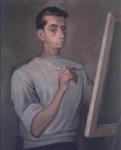

Orozco Romero self-portrait from 1948

David Alfaro Siqueiros had said of Orozco Romero,

“He feels the harmonious contradiction of opposing textures; mixes the smooth with the rough…In this lies his value; the objective with the subjective, the drama of intangible creation with the matter of the craft.”

RESEARCH PAPER

The painting represents two human forms, a woman in a long purple gown and an unclothed baby of indeterminate sex. They are placed within the confines of an elongated cubical, open on the viewer’s end and reaching far back into space. The woman’s form dominates the picture. Her head brushes the top of the enclosing cubicle. Her wide bell-like skirt brushes the wall behind, emphasizing Alice-like confinement in a space too small for her. In contrast, the baby is floating free just beyond the woman’s grasp. There is a small blue object, birdlike in appearance, which floats in the upper left corner.

Purple and grays in many tones predominate. What is most notable about the color is the surprising richness of tones achieved in a watercolor painting. Such richness is generally more common in oil or tempera. This gift for watercolors is one of the special attributes of Orozco Romero.

The title refers to the Tarasco Indians, an ancient people, who still occupy almost the whole present-day state of Michoacán. It is recognition of the debt Orozco Romero and others owe the artists of Mexico’s antiquity.

THE ARTIST

Born in Guadalajara in 1898, Carlos Orozco-Romero began his career during the social and political upheaval following the Mexican revolution. His first public recognition came for his caustic caricatures in newspapers. Although politically associated with the well-known muralists Diego Rivera and Jose Clemente Orozco (no relation) he had little personal affinity with their monumental propagandist art. In 1923 he was commissioned to do his own mural for the museum at Guadalajara. His talents were better suited to small easel painting however, and the unfinished work was eventually covered over. The experience had lasting value in that it taught him to work intensely doing sketches and life studies. It helped him to achieve the balance and stylization characteristic of his mature style.

The young painters of the Mexican School traveled to Europe on government scholarships with the intention of enriching themselves with the art of past centuries and with the ideas of their innovative European contemporaries. For Orozco-Romero, Europe was Spain. It was to Spain he traveled in search of his own sensitivity. There he was overwhelmed by Valazquez’s grandeur, Goya’s liberty of form and El Greco’s mysticism. His lifelong concerns with spatial settings and spatial illusion were shaped by the influences of the Flemish masters he saw in the Prado. During a stay in Andalucia, he came under the spell of its landscapes and Moorish architecture; the walls there haunted him. They seemed to him like those of a jail enclosing the splendor of patios and gardens. He was later to use those walls to define space in Tarascan Forms…..only one example of the lasting effect of these experiences.

Following his return to Mexico, Orozco-Romero painted realistically. La Familia, a portrait of himself, his wife, and his daughter demonstrates his close relationship to classicism at this stage of his development. In the next few years he experimented with portraiture, landscapes, surrealism, fantasy, expressionism and unique combinations of them all. He explained his Catholic tastes in this way:

“Painting is an art that expresses a whole and justifies the existence of man. Because it is so large we should not limit it…the artist who limits his life to one single sector limits his work.”

Throughout his development he was constantly inspired by his wife and daughter and used them as his models. He made frequent use of pre-Columbian forms as well and called these, “an influence I have on top of me.” The forms were often copied from popular art objects, of which he had a considerable collection in his studio. The abbreviated arms and massive hips and legs so often found in his paintings are a strong convention related to Mexican folk art. The round flaring skirt of Tarascan Forms (and suggested in Mujer y Nina) is molded into the form of a bell, which is from Oaxaca. He also used clay money banks from Guadalajara for models. In a 1940 New York City show, there were several oils taken from a bank fashioned in the shape of a woman’s head. The small blue object in Tarascan Forms is probably modeled on the painted clay bird figurines available in Mexican curio shops. Orozco-Romero’s archaeological collection, particularly a gold mask and some Tarascan idols are represented in Mujer y Nina and in several other paintings.

It is not only form that he repeats again and again. The sienna skin tones of his figures, the tendency to enrich surfaces with many tones of only two or three colors are clearly exhibited in Tarascan Forms and Mujer y Nina. It is a distinguishing trait shared by many members of the Mexican School.

Expressive Content

Tarascan Forms and Mujer y Nina are distinctly related in expressive content and taken together are an excellent example of this remarkable artist’s mature work. They can be interpreted as variations on the theme of maternal love, and as the larger theme of human love in a context of melancholy, pessimism and unworldly poetic mystery. Carlo Orozco-Romero went beyond the revolutionary climate of his time. His message is humanistic rather than socio-political. Despite the universality of these themes, he remains first and indisputably Mexican in his awareness and his expression.

Bibliography

Books

Agustin, Velazquez Chavez Contemporary Mexican Artists 1st edition

Mt. Vernon, New York: S.A. Jacobs The Golden Eagle Press 1937.

Brenner, Anita Idols Behind the Altar New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co. 1929.

Helm, MacKinley Modern Mexican Painters 2nd Edition New York: Harper Brothers 1941.

Myers, Bernard S. Mexican Painting in Our Time New York: Oxford University Press 1956.

Nelken, Margarita Carlos Orozco-Romero Nacional Autunoma de Mexico: Direction General De Publico 1959. (Translated by Diane Roby)

Schmeckebier, Laurence E. Modern Mexican Art Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press 1971.

Swanton, John R. The Indian Tribes of North America US Government Printing Office Washington 1952.

Toor, Frances Modern Mexican Artists Frances Toor Studios 1937.

Catalogues

SBMA “El Arte Moderno de Mexico” August 8 – October 11, 1970.

Institute of Modern Art Boston “Review of Exhibitions, Modern Mexican Painters” 1941.

Periodicals

Merida, Carlos “The Art of Carlos Orozco-Romero”, Mexican Life, May 1930,

pp 23-27.

Plaut, James “Mexican Maximum”, Art News, December 15-31, 1941, pp 10-13.

Prepared for the Docent Council by Judith S. Gainor, May 1980

Website Preparer Nancy Estes, March 2004, Ralph Wilson and Loree Gold, 2013

Orozco Romero – Mujer y niña (R)

COMMENTS

Carlos Orozco Romero was born in Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico, in 1898. Twenty years later he began his artistic career and was a prominent caricaturist for several papers in Mexico and abroad. He first appeared in public view as a member of the Siqueiros group, the Group of Revolutionary Artists, in Guadalajara (it was organized by Siqueiros, De la Cueva, and Zuno).

In the early 1920s Orozco Romero was granted a scholarship by his native state and was able to travel to France and Spain, where he presented an exhibition of his work in the Winter Salon in Madrid. After a year or two abroad he took up painting as a serious profession, continuing to experiment in different media—lithography, wood carving, furniture design, scenography. During this time he painted abstractions, and in later years his work was called surrealistic.

Orozco Romero received many commissions for portraits, which he executed in a polished and relatively classical style. For the most part he preferred to free paint and indulge his interest in forms and colors and textures. He was variously influenced by Rufino Tamayo, Carlos Merida, and Rodrigo Lozano, whose work he admired for its abounding originality and force. Many of his forms are copied directly or adaptively from objects of popular art, such as the model clay money banks from Guadalajara.

In his thirties he and Carlos Merida organized the Gallery of Modern Mexican Art under the patronage of the General Directorship of Civic Activities. Later he worked as a teacher of painting and drawing in different schools in Mexico City and as a class inspector for plastic arts in the Ministry of Public Education.

It has been said that his work was not local, not even national, yet it is easily understood because it was “fundamental”.