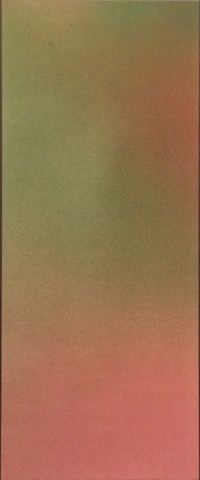

Jules Olitski

American, 1922-2007

OGV, 1966

acrylic on canvas

52 1/4 × 21 1/8 in.

SBMA, Gift of Robert B. and Mercedes H. Eichholz

2014.17.19

Undated photo of Olitski

"I have never felt bound by any art theory. I just try to get into the work and let it in some intense way be made." - Jules Olitsky

RESEARCH PAPER

Looking at OGV

Our OGV from 1966 (I am guessing the title refers to Olive Green Violet, unconfirmed) is among Olitski’s spray-gun, critically acclaimed, paintings, and it was the wide acclaim they received which led to his representing the United States at the 1966 Venice Biennale to his one-person show in 1969 at the Metropolitan, the first ever given to a living American artist.

Color Field Painting—a step beyond abstract expressionism

“In the seventies, Jules Olitsik was far ahead of the pack. His position as a so-called color field painter was difficult to dispute,” says Robert Morgan.

Deeply influenced by Hans Hofmann, Olitsky was naturally drawn to the experimental work of Helen Frankenthaler and others who began to soak the raw canvas in fields of color, eliminating the “action” painting of Pollock and Rothko’s gesture with its illusion of depth to provide a depthless space of floating color. Olitski’s innovation in the early 1960’s of spraying color directly onto the canvas, sometimes with mulitiple simulataneous guns, achieved the depthless surface long desired by post-abstract expressionists, The acrylic paint did not blend, as when applied with brushes or rollers, but maintained its distinct color, atomized onto the canvas.

In his introduction to the Corcoran Gallery 1967 exhibition catalogue Michael Fried wrote that Olitski’s technique “made possible the interpenetration of different colors, the intensity of each of which appears to fluctuate continuously,” and also “by atomizing color Olitski has atomized even disintegrated, the picture surface as well.”

Robert Morgan describes the spray-gun paintings as, “Olitski offers a saturated field of non-color [the writer’s term drawn from Ming Dynasty shimmering glazes], so evenly distributed and so effervescent as to catch the eye off-guard—as if the optic nerve were an organ with an independent mind. One simply enters the field as if form and space had no division, as if the subjecthood of the viewer and the objecthood of the work were inseparable.”

So not only is the raw canvas soaked with atomized acrylic but we soak in it, absorbing the shimmer, noticing the shifting relationships between areas of tint almost as though we were contemplating the surface of a lake in half-light. This painting is a great teacher in the rewards on prolonged viewing, as we move across the gallery for various viewing angles, the painting shifts, we experience one area more keenly and then another. I’m not surprised we have never seen it before.

Mercedes just couldn’t be without its mystery and sly, winking glimmer.

Artist’s Biography

After his Bolshevik father’s assassination in the Ukraine by the White Russian Army and his subsequent birth, his mother immigrated and settled them in Brooklyn. She remarried when he was 4 and gave Jules her husband’s name, though he later dropped the final “y” and replaced it with “i,” perhaps reflecting his life-long dislike of his stepfather.

Always interested in art, he took drawing lessons as a teenager, wining a scholarship to the Pratt Institute when he was seventeen and continued his studies at the National Academy of Design while taking classes at the Beaux Art Institute, both in New York City.

He became a citizen at twenty and then served in the military, and, like many aspiring artists of the period, used his GI bill to study in Paris for three years, where he attended the Ossip Zadkine School, and later the Academie de la Grande Chaumiere, culminating, when he was 29 in his first one person show at the Galerie Huit in Paris.

Returning to New York City he attended NYU receiving both a B.A. in Art and an M.A. in Art Education which led to his directorship of the Fine Arts department at Long Island University, where he continued to teach for seven years.

By 1958, at 37, Olitski was receiving increasing critical attention and held his first one person show in New York City at French & Co. gallery, where he came to the attention of the renowned critic Clement Greenberg, initiating a life-long association, in which Greenberg declared Jules Olitski “has turned out what I don’t hesitate to call masterpieces in every phase of his art.”

Olitski’s place in the art world

Olitski’s trajectory as a artist is unique. Following his decade in the 60’s and 70’s as the “reigning genius” and “dominating master” he did the unthinkable. He returned to gestural painting with heavily applied acrylic impasto. One of the most fascinating aspects of Olitski’s career is his utter disregard for art theory or for career building. Rather he was inspired by his interaction with the canvas, allowing the canvas and the paint to guide him. An exhibition at the Adelson Galleries in Boston in 2013 explored his late work, post-critical acclaim, and found it moving in a visceral rather than intellectual way, concurring with Clement Greenberg’s steady assertion that Olitski was a master. Torey Akers reviewing the 2013 exhibition terms Olitiski, “legendary abstractionist, painter’s painter, and veritable bastion of uncooperative modernism.” The Pop and Minimalist movements which took over in the 70’s didn’t interest him and, as Akers comments, “He returned to the matter-based painting style [of his Paris years] with a new-found sophistication, introducing a Jean Dubuffet-inspired savagery.”

Prepared for the SBMA Docent Council by Ricki Morse, June 2014

Bibliography

Torey Akers, “Superb Irrelevance,” Arts Editor, 2013.

Robert C. Morgan, “The Seventies, Painting and Sculpture, Paul Kasmin Gallery,” The Brooklyn Rail, New York, 2006.

The Art Story Foundation, 2014 (www.theartstory.org/print.html?artist=olitsky_jul)

1982 The Bear Island Studio, NH with Clement Greenberg, Elizabeth von Wentzel, and Kristina Olitski on ladder

SBMA CURATORIAL LABELS

Known for creating radiant color harmonies and shifts that became a characteristic of Color Field painting (also known as Post-painterly abstraction), Jules Olitski rose to prominence in the 1960s, and in 1969 became the first living American artist (and third living artist) to be given a one-person exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Olitski was born Jevel Demikovsky in Snovsk, Russia, in 1922, in the wake of his father’s execution by the Russian government. He immigrated to New York City with his mother, and in 1942 he became a United States citizen. Soon after, he was conscripted into the U.S. Army. With the aid of the GI Bill, the artist lived in Paris from 1949 to 1951, where he deliberately isolated himself from both the Old Master tradition and contemporary trends in order to develop his own style.

Treating the canvas as an open field, Olitski used staining methods, much like the European tachistes and his American contemporaries Helen Frankenthaler, Morris Louis, and Kenneth Noland. In 1965, his interest in the relationship between paint and canvas expanded through his use of a spray gun, allowing him to liberate color by literally atomizing it. He once stated that ideally his pictures should appear as “nothing but some colors sprayed into the air and staying there.”

- Colefax Gallery in honor of the Robert and Mercedes Eicholz Collection coming to the museum, June 2014