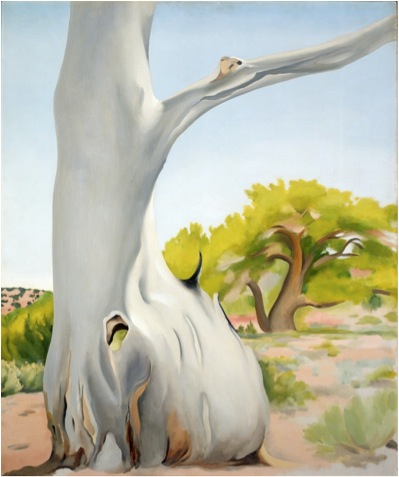

Georgia O'Keeffe

American, 1887-1986

Dead Cottonwood Tree, 1943

oil on canvas

36 x 30 in.

SBMA, Gift of Mrs. Gary Cooper

1951.6

Georgia O'Keeffe in 1962 at her ranch in Abiquiu, outside Taos, New Mexico

RESEARCH PAPER

In the early 1940’s Georgia O’Keeffe began painting the cottonwood trees that grew in the river basin below the mesas in Abiquiu, New Mexico. She featured them in a series of paintings begun in 1943. This series of tree paintings was a subject of great interest to the artist, who is best known for her unique depictions of objects from nature.

O’Keeffe’s acute observation of the natural world grew out of her deep, almost transcendent love of nature, particularly in the vast rugged spaces of the Southwest. In the Dead Cottonwood Tree, O’Keeffe emphasizes the smooth, curved shape of the trunk of the living cottonwood in the background. In this magnified dead cottonwood the viewer is able to look through a hole in the trunk to see the green foliage behind. This techniques is also seen in O’Keeffe’s pelvis paintings where nature is revealed through the dry bones of dead animals. The clear close-up view of the dead cottonwood in the foreground, contrasted by the softly tinted and slightly out-of-focus living cotton wood in the background is an example of the influence of photography in O’Keeffe’s paintings. In Dead Cottonwood Tree, brilliant, clear blue sunlight gives us a notion of the hot, dry air of the desert. The light pastel colors contrast gently with each other. Bold shapes and color are very important in this work as they are in all of O’Keeffe’s paintings.

Georgia O’Keeffe was born in a small town in Wisconsin in 1887. She was determined to be an artist from an early age. She studied at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Art Students League in New York City. She taught art in Texas and Virginia. At the age of twenty-five O’Keeffe took a summer course given by Alon Bement at the University of Virginia. Bement’s teaching was based on the art educator Arthur Wesley Dow’s adaptation of the principles of Japanese art. Two ideas from Bement’s course that interested O’Keeffe were the balance of light and dark and the organization of flat patterns on surfaces. She recalled that it was ‘filling space in a beautiful way.’ She also was influenced by the Japanese idea of depicting whole images and not fragmenting them. She taught Dow’s method of painting for four years in schools in Texas, Virginia and South Carolina. O’Keeffe had also about this time, seen the Rodin drawings that were on exhibition at the Gallery 291. She was also influenced by Wassily Kandinsky’s theory that each color has a spiritual vibration and that artists must first discover their innermost feelings and then create forms and colors that capture these essences. Feelings were extensions of the artists. spirit and soul, as opposed to imitation of Old Masters and scientific methods of composition. O’Keeffe adopted the theories about color and form both in her teaching and in her own art.

In 1916, O’Keeffe met Alfred Stieglitz, whom she would later marry. Stieglitz supported and promoted O’Keeffe’s art thought his Gallery 291 in New York City. Stieglitz also was exhibiting the works of important American Artists—John Marin, Marsden Hartley and Arthur Dove, Max Weber and others. At this time, New York was exploding with Post impressionism, Cubism and Abstract Expressionism. Stieglitz felt that O’Keeffe’s work was significant in that she expressed motions in her paintings that could only come from a woman’s perspective. While visiting in New Mexico, O’Keeffe began collecting old dry bones from the desert. She said that they reminded her of life, not death, although death has sometimes been attributed to her paintings of the skeleton bones. At this time, she also began a series of desert landscape paintings.

O’Keeffe was influenced by the work of Arthur Dove. What O’Keeffe most admired in Dove was his ability to create abstract compositions that were actually based on an observation of nature. Dove’s use of simple subjects given large amounts of space and landscape forms are reflected in O’Keeffe’s paintings. O’Keeffe’s Evening Star series is very closely related to Dove’s Sunrise. While O’Keeffe’s colors are bright and livelier than that of Dove’s often muted and dull colors, shapes and color dominate both artist’s paintings.

O’Keeffe was also greatly influenced by the photographers of the period: Paul Strand, Imogen Cunningham, Johan Hagemeyer, Paul Haviland, and Edward Weston. Most of the painters in Stieglitz’s circle shared his appreciation of photography as an art form. O’Keeffe was naturally quite familiar with the current ideas in this field and often adapted them to her work. Of particular influence was Paul Strand. His photographed details of objects in such extreme magnification that they lost all pictorial reference, becoming pure abstractions of pattern, shape, and line greatly influenced O’Keeffe.

O’Keeffe’s geometric abstractions and enlarged flowers and plants follow Strand’s inspiration. Stieglitz’ and O’Keeffe’s influence on each other can be seen in their choice subject matter, which are similar, even though their approaches are vastly different. For example, both artists depicted clouds. However, the intense emotional passion expressed in Stieglitz photographs, such as the Equivalents, a cloud series, is rarely evident in O’Keeffe’s more coolly executed images. His romantic viewpoint is also at odds with O’Keeffe’s emphasis on analytic observation.

O’Keeffe lived in New York City from 1918 to 1949. During this time she painted many cityscapes and skyscrapers which, in their technique and iconography, reflect a relationship with the Precisionists, a group of artists in American whose work shows influences of Cubism combined with the machine aesthetic of Picabia and Ducamp. Precisionists celebrated post-war industrialization and the beauty of technology, relating to photography. O’Keeffe, during this time, had begun painting the flower series, for which she is most famous. O’Keeffe said that flowers are relatively small, and if she were to paint them as she saw them, she would paint them small, and no one would notice them. So she painted them big, so that everyone would have to notice them, even busy New Yorkers. That was a photographic idea, to enlarge, zoom and crop the flowers.

O’Keeffe explored every imaginable color combination in her paintings. Her paintings are often as much about color and shapes as about the subject matter. She was a modern painter often painting abstract and representational pictures of the same subject. O’Keeffe’s long life of 98 years gave her a broad reach back and forward in time. Her last series of paintings, Sky Above Clouds, has been compared to the Color-Field painters of the late sixties. O’Keeffe’s life was devoted to her art. It is through painting that O’Keeffe filtered all experiences.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Shirley Waxman