Emile Nolde

German, 1867-1956

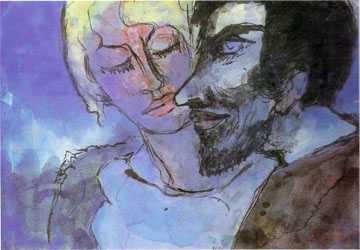

The Lovers (Self Portrait with his Wife, Ada) , 1932

watercolor on paper

13 1/4 x 19 1/2 in.

SBMA, Gift of Margaret P. Mallory

1991.154.25

A photograph of the couple in their garden when they were in their sixties.

RESEARCH PAPER

Emil Nolde rose to prominence in the early twentieth century for his bold style and psychologically penetrating subject matter. His work exemplified the ideals of German Expressionism, yet his diverse oeuvre defies categorization. Over the course of his prolific career, which spanned five decades and two World Wars, Nolde worked as a furniture maker, a ceramicist, a painter, and a graphic artist. As a pioneer and member of the avant-garde, his work was praised, publicly persecuted, collected by museums, and unceremoniously destroyed. Yet through the successes and the struggles, two things remained steadfast: the love, support, and assistance of his wife, Ada, and his unwavering need to create.

The Santa Barbara Museum of Art's watercolor entitled The Lovers (Self-Portrait with his Wife, Ada), exemplifies the love and devotion that characterized Ada and Emil's relationship. Painted in 1932 when the pair were in their mid 60's, the artist has depicted a young man and woman sharing a private moment. Visually, Nolde demonstrates this intimacy through a variety of techniques. First, he compresses and crops the space surrounding the couple. For instance, Emil's right shoulder seems almost nonexistent so that Ada's shoulders and torso can appear closer to her husband's body. Though awkward and unrealistic, these body positions heighten the emotional intensity of the artwork. Secondly, Nolde directs the viewer's attention by eliminating distracting details. The vivid and brilliant blue background instantly engages the viewer, yet it does not detract from the central focus of the artwork: the physical and psychological connection between two lovers. In fact, the choice of blue only adds to the dreamlike, ethereal quality of the work. The couple does not exist in real time. Without a background, and with the focus squarely on their faces, their presence and their relationship are timeless and eternal.

Nolde creates mood and emotion through quintessential elements of German Expressionism: bold color, quick, choppy lines and gestural brush strokes. He also applies heavy washes of watercolor to the thick absorbent paper. As a result, the paper warps, creating small creases and pockets that add volume and texture to the image. The materials combined with the subject matter, engages the viewer on an intuitive level. Ada appears reflective, savoring the closeness she shares with her husband. Her head is tilted slightly; her eyes closed. The fullness of her pink lips and the yellow of her hair are intensified by their contrast with the blue background. Compared to Ada's soft, tender demeanor, Emil's profile emotes strength and conviction. Gazing beyond the edges of the paper, he personifies the visionary. He is a man engaged in the moment, yet driven by other internal desires.

Nolde's life was full of successes and failures, great joy and love, as well as tragedy and disappointment. Ada remained his constant companion for more than forty years, supporting her husband artistically as well as emotionally. This image is visually stunning, yet it tells the story of a love that withstood war, sickness, public condemnation, and extreme personal loss. Theirs was a lasting love, one that continues to endure at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art.

Born Emil Hansen on August 7, 1867, Nolde was raised by peasant parents in a land that was alternately German and Danish. Nolde's father was a farmer of Frisian-German ancestry who hoped his son would farm the land the family had owned for nine generations. Nolde's goals differed from his father's and, at the age of seventeen, he left home and assumed jobs in the industrial and decorative arts. Prior to becoming an independent artist at the age of thirty, Nolde worked as a wood carver at Sauermann furniture factory in Flensburg, Germany, and as a drawing instructor at the Museum for Industry and Craft in St. Gallen, Switzerland. It was not until 1897, when he experienced financial success creating novelty postcards with images of personified mountain peaks, that he committed himself to artistic production as a full time profession. It was during these early years that he met Ada Vilstrup, then a Danish theater student. The two married in 1902 and, that same year, Emil shed his family name and took Nolde, the name of his birthplace, as his artist's name.

Nolde's marriage to Ada would have a lasting and profound influence on his work in the years to come. Most importantly, she supported his work unconditionally. She managed the day-to-day concerns associated with Nolde's career including maintaining extensive records of his artistic output. Most tellingly, however, she assisted in the art making by creating impressions from woodcuts and by assisting in the titling of prints.1. This job, though seemingly small, is put in perspective knowing that Nolde produced over five hundred prints, including woodcuts, etchings, and lithographs between 1898 and 1937.2. Ada's devotion to her husband's work becomes even more poignant given her chronic frail health and her frequent confinement to sanatoriums.

Over the next twenty years, as Nolde's reputation began to rise, two events marked and shaped his artistic career. The first occurred in 1906 when Nolde was invited to join the young Dresden based art group Die Brücke (The Bridge). Though he left the group in 1907, Nolde entered into a prolonged phase of artistic creativity immediately following his departure. The second event came in 1913 when Nolde and Ada joined Germany's Department for Colonial Affairs' medical-demographic expedition to New Guinea. As the unofficial artist, Nolde captured the peoples of Russia, Korea, Japan, China and New Guinea. Nolde's encounters with the pulsing, vibrant lives of peoples untouched by “civilization” reawakened the instinctive and primitive forces within himself. These forces are given visual form in the numerous woodcuts, lithographs, and oil painting he created after his trip, most notably in the dynamic images of native dancers.

Despite Nolde's emergence as a successful, respected artist in the early decades of the twentieth century, he faced his harshest criticism the latter years of his life with the rise of Germany's National Socialist Party. In 1937, over one thousand of Nolde's paintings, prints, and watercolors were seized from German museums by the German government. Many were exhibited in the “Entartete Kunst” (Degenerate Art Exhibition) that same year. The Nazis' attempt to condemn modern art, and Nolde's work specifically, is ironic given that Nolde sought the group's acceptance. He ascribed to the party's ideology and felt he could further their message through his distinctive German style. Ultimately, many of his works were destroyed and he was forbidden to paint. Despite public persecution, between 1938 and 1945, Nolde secretly produced small watercolors, numbering over one thousand and collectively named the “Unpainted Pictures” at his house in Seebüll, in northern Germany. During this time, Nolde worked exclusively in watercolor fearing that the smell of oil paint would alert the Gestapo on their regular visits to his home.

Nolde suffered another crushing blow in 1944 when his Berlin studio was bombed; most of his personal records were destroyed. Two years later, his beloved Ada died. Nolde resumed oil painting after the war and remarried in 1948 to Jolanthe Erdmann, the twenty-six year old daughter of a friend. On April 16, 1956, he died at his house in Seebüll. He was eighty nine years old.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Jennifer P. Steffen, December 2005.

1. Ackley, Clifford S., Timothy O. Benson, and Victor Carlson. Nolde: The Painter’s Prints. (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1995), 14-15.

2. bid.

Bibliography

Ackley, Clifford S., Timothy O. Benson, and Victor Carlson. Nolde: The Painter’s Prints. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1995.

Behr, Shulamith. Expressionism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Grosshans, Henry. Hitler and the Artists. New York: Holmes and Meier, 1983.

Herbert, Barry. German Expressionism: Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter. London: Jupiter Books, 1983.

Rigby, Ida Katherine. “Expressionism and the Third Reich.” German Expressionism: Documents from the End of the Wilhelmine Empire to the Rise of National

Socialism. Ed. Rose-Carol Washton Long. New York: G. K. Hall, c1993.

Vergo, Peter, and Felicity Lunn. Emil Nolde. London: Whitechapel Art Gallery, 1996.

Websites:

www.nolde-stiftung.de

POSTSCRIPT

Emil Nolde is recognized as one of the most powerful representatives of German Expressionism. His birth in a quiet, unspoiled countryside in Northern Germany, to a ninth generation of peasant farmers, did not deter this lonely, morose and often confused and frustrated individual from achieving artistic distinction. Young Emil felt a mystical attachment to the austere and powerful environment where he lived. Throughout his life his imagination was to be sustained by the insight he gained as a child running in the fields of the land that was marked by bleak witers and intoxicating springs.

At seventeen Nolde left this land to avoid becoming a farm laborer. In the city he became a furniture woodcarver, though always finding time to draw and paint. Around the turn of the century he traveled to Berlin, Munich, Copenhagen and Paris. But wherever he traveled, Nature was always alive for him, arousing his excitement and crying out to be painted.

At thirty-five he finally gained enough confidence to devote his life fully to art. He was ready to acknowledge that the landscape that he had turned his back on, played a decisive role in shaping his sensibilities; hence he decided not to be known as Hansen, his family name, but as Nolde, the name of his native village.

Nolde was a deeply religious man, and he is most famous for his paintings of Old and New Testament subjects, in which he expresses intense emotion through violent color, radically simplified drawings and grotesque distortion. The majority of his pictures, however, are landscapes, worked with gloriously vivid colors. He also was a prolific etcher and lithographer.

The SBMA Ala Story Collection contains Nolde's THE LOVERS (SELF PORTRAIT WITH HIS WIFE ADA), 1932. This watercolor, painted when he was 65 years old is a fine example of a technique he pushed to a highly advanced point. Employing an absorbent Japan paper, he moistened it and then applied the watercolor, permitting the pigments to flow into each other, controlling their movement with tufts of cotton. This technique permitted him the free improvisation he desired. The colors of blue and pink range from the lightest transparency to deep and full opacity. In this spontaneous wet-on-wet technique, Nolde welcomed the accidental, as he controlled it. When the composition of THE LOVERS was finished he took a deep breath and said to his wife Ada, "This is the best portrait of our superior being." The double portrait captured the love of his very own happiness. His works achieve a startling and ephemeral beauty which stands today, of his century, to confront us with its intensity and truth.

- Elaine Johnson, Nolde's "The Lovers" Epitomizes his Artistic Passion