Malcolm Morley

British, born 1931

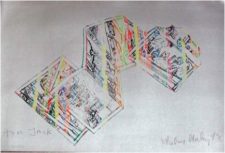

Untitled, from the portfolio, "Arles/Miami", 1973

lithograph

23 1/4 x 33 1/8 in.

SBMA, Gift of Mr. Richard A. Brodie

1979.75.1

Undated photo of Malcolm Morley

“The idea is to have no idea,” the artist has said of his practice. “Get lost. Get lost in the landscape.”

'The moment anyone said my work was art, I had this block – I took a long time to find myself'

- Malcolm Morley

Also from the series but not in the SBMA collection, this is a great discription of the process: "Arles/Miami" Portfolio of 5 lithographs published in 1973. These were the first original, hand drawn prints ever created by Morley and, as such, are important for any serious collection. . This image was printed in a rainbow of colors on a silver background. 24"x34" on Arches paper. Signed in pencil by the artist and dedicated to the Director of the Atelier aside from the edition of 150. Subject matter is a fold-out picture postcard of Miami. "This very unique print was made by printing it in 20 colors using 5 stones with 4 colors each. As a result of scrupulous matching, the image shifts color in narrow ripples from crimson to purple to green to dark blue to peacock blue to yellow and so on. The linear outline is dissolved by the elusive definition and by the rhythmic repetition of color." -Lawrence Alloway

COMMENTS

Malcom Morley is a contemporary British painter. Working in a variety of styles—from Photo Realism to Neo-Expressionism—Morley's work has shifted through multiple distinct aesthetic periods over the course of his prolific career. Born on June 7, 1931 in London, England, he experienced a troubled childhood, during which he first took up painting while serving time at the Wormwood Scrubs prison. Following his release, he quickly enrolled at the Camberwell School of Arts and the Royal College of Art, initially adopting an Abstract Expressionist style of working. While later living in New York, he began making Photorealist paintings after befriending Pop Art icons Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. Throughout his career, Morley’s work has retained a common thread of subject matter: aviation, automobiles, locomotion, and watercraft. A significant influence in 20th-century painting, he was the recipient of the 1984 Turner Prize, and held a teaching position at the School of Visual Arts from 1970 to 1974. Morley lives and works in Bellport, NY.

http://www.artnet.com/artists/malcolm-morley/

When the British-born artist, and inaugural Turner prize-winner, Malcolm Morley became an American citizen in 1991, the presiding judge at his ceremony gave a short speech. "They always want to say something about what it is to become an American," recalls Morley. "And this judge spoke about how diversity worked better than the status quo. It really stayed in my mind because diversity is something the art world has always had a problem with, but only for a while. Then time goes by and they catch up with what's new or what's different."

Morley's life – which has included prison, psychoanalysis and five marriages – has not been one much troubled by the status quo, and the accompanying diversity in his career has seen him along the way associated with the Euston Road school of painting via Cézanne, abstraction, abstract expressionism, neo–expressionism and post-pop. "But it's always worth remembering that as soon as a movement is named you know it's over," he laughs. "Picasso didn't call those paintings cubism. He was just trying to get to another layer of realism."

The "ism" most closely associated with Morley is what critics have called photo-realism, but he prefers to describe it as super-realism, "not because I'm saying the art is super, but because it reminded me of Malevich's suprematism". Morley's intricately accurate 1960s paintings of postcard images range from horse races to beach scenes, royal pageants and, most characteristically, ocean liners. And at a time when, as Norman Rosenthal, curator of a new retrospective of Morley's work at the Ashmolean museum in Oxford, puts it, "issues concerning the democratisation of art and life became ever more central to the intellectual and political discussion on both sides of the Atlantic", Morley's work was both democratic in its use of postcard images, and also in its method of production.

By dividing the original image and his canvas into corresponding grids, Morley systematically painted the work one tiny area at a time. "I discovered there's no such thing as space in painting, only what a mathematician would call 'area'," he says. "So each section receives the same attention, has the same value and you get away from the idea of foreground and background. And then a strange phenomenon occurs: if you see a reproduction of the painting it does looks like a photograph, but when you see the physical reality of the surface it seems to work on you through your central nervous system. Paradoxically, a sort of stereoscopic feeling emerges even though I painted every section equally. You find yourself in a strange mind-set."

Despite his success with super-realism, it is just one of the styles that feature among nearly 50 years' work on loan from the Hall Foundation, his most comprehensive collector, in the Ashmolean show. "Some of the changes I've been through do seem to have confused people," he acknowledges, "but there was no other option. There's big Malcolm who makes the work. But there's also little Malcolm who lives here" – he gestures at his sternum – "and who is really in charge. Sometimes big Malcolm takes on something that little Malcolm doesn't like and that is the end of it. A valve shuts down and suddenly I lose the wherewithal to do it. It can be traumatic. One minute you're going along being successful and satisfied, the next you are falling off a cliff and thinking you're finished. Then something happens and work starts again, but I don't take it for granted. It always feels more like a lucky break."

The 82-year-old Morley's latest preoccupation is a series of paintings inspired by his interest in the 18th century ("I fell in love with the period, which was a great one for the British")and his Long Island studio is adorned with his portraits of Wellington and Nelson, toy soldiers as well as models of cannons, homemade cannon balls and man-of-war gun ports. "I'm currently reading up on Nelson and it turns out he was a total son-of-a-bitch," he says. "Schoolboys are brought up on his heroism, but in fact he was a real nerd." More than 50 years after Morley left the UK he says its influence on him remains strong, but he also confesses that as a young man his thoughts were less on the likes of Nelson and more on his own predicament. "Things were so fucked up I didn't really have a wider view. The strongest feeling I had was that I was nobody, and that I wanted to be somebody. Real Marlon Brando On the Waterfront stuff. 'I coulda been a contender. I coulda been somebody.'"

Morley was born in Stoke Newington, London, in 1931. He never knew his father, and when his mother later married a former Welsh miner Morley was brought up under the name Evans. The definitive memory from a troubled childhood was of making a balsawood model of the navy battleship HMS Nelson. "I loved making models and I'd just finished this one and put it on a windowsill overnight ready to paint in the morning. That night we were blown up by a German V-1 bomb, a doodlebug, the whole of the wall was blown away and, of course, the model was lost, as was our home. Years later, when I was in psychoanalysis, a memory of the bombing came up and I realised that all those ships I'd done had to be to do with me trying to paint that battleship I never finished."

Morley was evacuated to Devon and then sent to a naval boarding school in Surrey. By the age of 14, with what family life he had in some disarray, he left to be a galley boy on a transatlantic tug. Returning to England he became a petty thief, and a period in reform school was followed by a three-year prison sentence for burglary. He eventually served two years in Wormwood Scrubs before being released, aged 20, on parole. It was in prison that he began to paint.

"There was little or no art in my early life beyond my grandmother saying that anything neat looked like it had been done by 'a Royal Academician'. But then in jail I came across Vincent van Gogh in Irving Stone's novel Lust for Life that had been made into the Kirk Douglas film. Van Gogh's art struck me as crude, although of course it was not crude at all, but more importantly it seemed something I could do. I could draw, and the idea that you could make something of yourself through art was very strong."

After leaving prison Morley spent some time as a waiter in the artists' colony in St Ives, Cornwall. "And although it wasn't really the plan, I got to meet artists and there was such a sense of friendliness that I guess I turned the art world into my family. It was quite a conscious thing. I was very aware of that feeling of acceptance, as well as the fact that if you were an artist you could get good girlfriends. That was part of it, too."

Meanwhile, in London, his parole officer had arranged for some art schools to see the work he had produced in prison and Morley was offered a place at the Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts in 1952, "where I discovered art history and rushed to this idea that other people before me had done this thing". He moved to the Royal College of Art a year later, "sort of through the back door because I didn't have the schooling. But I'd been taken up by one of the owners of Lyons tea houses, Julian Salmon, a big patron of the arts, who paid my fees." At the Royal College fellow students included Peter Blake, Frank Auerbach, Joe Tilson and Richard Smith. "I felt very naive next to someone like Dick Smith, who was so sophisticated, but people took to me and I had a great time, although I didn't produce that much work. The moment anyone said it was art, I had this block and I took a long time to find myself."

Despite his lack of productivity, Morley enjoyed a prestigious introduction to the art market when an early painting of a grand house on Richmond Hill – which he later discovered had been built for Joshua Reynolds – was bought by the house's then owner, the actor John Mills. Years later Morley bought the painting back from Mills's daughter, Hayley, and it now hangs in his American home. That early work was signed Evans, but Morley returned to his birth name just a couple of years later when he had to apply for a passport for his move to America in 1957. His enthusiasm for the place had been fired by an important Tate exhibition of contemporary American art, but the more immediate reason for his emigration was "a girl I met on the number 37 bus".

He followed her back to her home in America and they got married. "It didn't last long, a year or so, but I knew I'd stay." Gradually he worked his way into the New York art world and began to hang out at the Cedar Street Tavern where Willem de Kooning – "very modest, very nice to younger artists" – Jackson Pollock and Franz Kline had drunk. He became close to Roy Lichtenstein, who later arranged teaching jobs for him, and met Salvador Dalí and Andy Warhol - "shy, polite, treated me like an elder statesman" – as well as Barnett Newman, who gave him early encouragement.

Morley lived in lower Manhattan when Spring Street was under the direct control "of a notorious mafia boss and was therefore one of the safest place in the city. But artists are city planners. They go to an area that is broken down and when some of them become successful the Wall Street guys think it's cool to follow because they can seduce girls better in a loft. Then the boutiques move in, then the restaurants … "

Arriving at the tail end of abstract expressionism he had little in common with the younger generation still aping the style, yet with his friend Lichtenstein owning the territory of comic books, "and the coke bottle also occupied, all that seemed left to me was ships". His initial efforts at painting ocean liners at pier 57 in New York failed because they were simply too big to take in. "So I got a postcard and divided it into a grid, a technique we'd used in art school but I'd forgotten about when I was busy being an abstract expressionist. My friend Richard Artschwager used grids and I learned a lot from him and felt that this was somewhere I could go. It was the total opposite of abstract."

He says the laborious process made the works "excruciating to paint, and I couldn't find brushes small enough. But getting to that end result was so important to me. When I had this conversation in analysis about being bombed in the war it did make sense and was almost like having a genie in the lamp. All I had to do was rub that memory for the genie to appear."

Morley describes himself at the time as "very neurotic. Constantly acting out in dramas to do with the other sex. Going into analysis was a big commitment, but I went for it big time."

After four previous marriages he has been with his Dutch-born fifth wife, Lida Kruisheer, for the last 26 years, enjoying unexpected contentment in their home/studio about an hour-and-a-half's drive from New York City.

Back in the early 1970s it was a sense of anger that led him to move away from super-realism, even though it had established his reputation. "There was a guy in New York who worked in a gallery and travelled round America to art departments showing slides of these paintings, and within a year there were 100 guys doing versions of them: race horses, diners. I felt totally eclipsed and as if something had been taken away from me."

The painting most identified with the end of this phase of his career is Race Track (1970) on to which Morley applied a large red cross over a super-realist depiction of a South African horse race. "It was simply a gesture of frustration, but that's where the unconscious comes in. Here was Malcolm's X on a South African subject entitled Race Track. I wasn't thinking politically when I did it, but it precisely reflected my emotions and my views."

In subsequent years his brushstrokes became larger, he painted nature and made use of toys he described as "archetypes of the human figure". He won the first Turner prize in 1984 following an exhibition at the Whitechapel gallery put on by a long-term supporter, Nicholas Serota. "It wasn't so hot back then, and I got the smallest amount of money they've ever given out." There was considerable criticism that the prize had been given to someone living in America. "Some of it was over the top, and while I sometimes get upset at criticism, my attitude is usually 'if you don't like that, just wait until you see the next thing. You really won't like that."

He has viewed with interest developments in the UK, and says he liked the way that the YBAs "somehow found a way of reinventing themes. When Damien Hirst first appeared I thought this was the real thing. But I've never seen anybody go down so fast, and I was rather saddened because I really thought he had something to offer."

Morley's own productivity increased into his 60s and 70s. Ships, model soldiers, aircraft, toys all became regular parts of his repertoire of imagery, but whatever the ostensible subject matter, there was also a remarkable degree of consistency in his approach. "I was once on a boat trip in England and was asked what I did. I said I was a natural scientist, and was then asked what did that entail. 'Well,' I said, 'I study contours, mass, tone, colour, edges.' And that has stayed much the same."

He says Robert Rauschenberg once told him about an important collector visiting his studio and saying how much he liked his early work. "Bob pointed at what he was doing that day, and said, 'This is my early work.' And he was right. New work is always early work. And so seeing work from a long time period together is pleasurable because not only do you see the diversity, you also see some fidelity. It's something I arrived at after a long time of trying to pare things down to their essentials. Things change, but they are still true to something. And with that you've got it. Diversity and fidelity."

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2013/oct/04/malcolm-morley-interview