Thomas Moran

English, 1837-1926 (active USA)

Mountain Landscape, 1864

oil on canvas

20 1/4 x 28 1/4 in.

SBMA, Gift of Mrs. Ina T. Campbell

1942.21.1

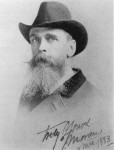

Thomas Moran photographic portrait, Christmas card, 1883 Yellowstone

"Here are no lofty peaks seeking the sky, no mighty glaciers or rushing streams wearing away the uplifted land. Here is land, tranquil in its quiet beauty, serving not as the source of water, but as the last receiver of it. To its natural abundance we owe the spectacular plant and animal life that distinguishes this place from all others in our country." - Thomas Moran

RESEARCH PAPER

Thomas Moran was a real Pre-Raphaelite and a romantic. But he was his own man. James Mallord William Turner’s work was his ideal and was a steady influence. However, Thomas Moran was self taught and didn’t believe painting could be taught.

His early work could be considered as similar to landscapes of the Hudson River group. However, his love of nature was in its pristine state. Landscapes spoiled by encroachments from civilization held little charm for him in the common places of human life, either urban or rural.

On May 2, 1872, Moran’s The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone drew a curious throng to Clinton Hall in New York City. Directors of the Northern Pacific Railroad, the press, the literati, the artists and the rich were dazzled with his painting. His work did much to convince a doubting Congress to decree a national Park (Yellowstone National Park). On June 10, 1874, Congress voted ten thousand dollars (a large sum for a painting in those days) to Moran for his huge painting (7 feet by 12 feet). It was hung in the Senate lobby.

The advent of and tendency toward giant canvases marked the culmination of the Hudson River school and the rise of what might be called the Rocky Mountain School. Moran, in finding the Yellowstone, found himself as an artist. His reputation was now made.

Thomas Moran was never avant-garde. Coming to maturity at a time when British tradition was still a force in American art, he trained himself in that tradition, especially as it converged in the work of J.M. W. Turner. Although travel in Europe exposed him to the work of continental schools and his pictures sometimes reflected the influence of Corot and Rousseau, Moran never departed from essentials of an Anglo-American style and technique.

When winds from France at last prevailed in American studios, he let them blow, unmoved, and held aloof from the currents they set in motion. He remained the obdurate romantic. He looked to nature for his inspiration, not to serve up slavish copies of natural scenes, but to present the spectator with the impression produced by nature on himself. His own response to nature was the real subject. Like his master Turner, he became a tireless traveler in the search of nature’s variety.

The result was a teeming accumulation of impressions caught by paintbrush, the lithographers crayon, or even the etchers needle.

No doubt some sympathetic attention to the newer European techniques would have bolstered his later reputation and made him seem less antiquated at the height of his career, but he regarded such methods as fads and persisted in his ‘archaic’ technique, carrying his nineteenth century style far into the twentieth.

He lived to become the senior member of the National Academy of Design and when he died in 1926, he was called the dean of American painters. By then landscape was slipping from esteem. (In such an atmosphere, the landscapes of Moran’s period clog the basements of museums and many an honored contemporary has been forgotten). Yet no matter how dim his reputation might have grown, Moran has never been in danger of oblivion. His work can be found in the Metropolitan Museum and in the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan. It can also be found at municipal museums in Brooklyn and Newark, the Heckscher Museum at Huntington Long Island, the Gilcrease and Philbrook galleries in Tulsa, the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; in the collection of the Santa Fe Railroad and the I.B.M. Corporation as well as in many private collections. Its creative vigor has always had the power to rouse interest afresh and at intervals, people suspect that in him we have ‘an old master,’ not incomparable with Turner and Claude Lorrain.

It is true that Moran, perhaps more than any other American painter, is responsible for making the American people aware of their great natural heritage. He painted landscapes of eight national parks and monuments: Yellowstone, Zion, the Grand Canyon, the Grand Tetons, the Mount of Holy Cross, Devil’s Tower and the Petrified Forest. His works are topographically interesting and he was not an unwise choice as a painter to accompany the various expeditions, which he joined to survey the West during the 1870s.

Prepared for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Docent Council by Jack Mannion, March 1991

POSTSCRIPT

By 1876 Moran had established himself as a leading landscape painter, rivaling German-born Bierstadt (1830-1902). The two artists competed for patronage and congressional favor for years. Bierstadt, whose romantic vistas took even greater liberties with reality than Moran’s, painted exclusively in oil; Moran, on the other hand, became a master of watercolor.

Blessed with energy and good health, Moran continued to travel and paint well into his 80s. He and his daughter Ruth spent many winters at El Tovar Hotel in the Grand Canyon, where the views inspired the small but panoramic A MIRACLE OF NATURE (1913), painted when Moran was 76.

During Thomas Moran’s long and prolific career he produced some of the most remarkable landscapes of the nineteenth century. When Moran died at his home in Santa Barbara, CA, in August 1926, just before his 90th birthday, he was hailed as “the dean of American landscape painters”. And, in the three decades since Moran had first visited Yellowstone, Congress had expanded the initial legislation setting aside additional "parks" including Yosemite in 1890. Inextricably linked through his paintings to numerous landscapes that eventually became national parks, Moran would one day also be known as the "father of the national park system.”

Prepared by Loree Gold, 2012

Bibliography

http://hoocher.com/Thomas_Moran/Thomas_Moran.htm

Stephen May is a freelance writer in Washington, D.C., Reprinted courtesy Southwest Art, February 1998, Smithsonian American Art Museum.

The painting that made Thomas Moran famous, was lent by the Department of the Interior Museum to the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and can be viewed by the public on the 2nd Floor N Lobby. The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, 1872 (L.1968.84.1) Born: Bolton, England 1837 Died: Santa Barbara, California 1926. Oil on canvas mounted on aluminum 84 x 144 1/4 in. (213.0 x 266.3 cm.) Remarks: Frame: 111 x 170 in.

COMMENTS

Mountain Landscape was the first nineteenth-century American painting in the SBMA’s collection. Purchased in 1942, this landscape by Thomas Moran joined more "contemporary" works and, in 1945, the Museum acquired the celebrated primitive painting The Buffalo Hunter. This strong emphasis on collecting American art was unusual among the country's museums in the 1940's.

The painting in our collection, dated 1864, can easily be mistaken for a western landscape, however, the picture was probably an artistic invention. In 1867 Moran had not yet crossed the Mississippi River or seen the Rocky Mountains.

Loree Gold, 2012